Suppleness Component

Isn’t Getting Supple Simple?

It has often been said that the simplest approaches work the best, and on this basis the simplest way to get supple is to go out and practise stretching!! Right? Yes, providing the athlete knows which muscles are stiff and short and need stretching!! As we will see at APA we use the term ‘Suppleness’ to mean more than just being ‘flexible;’ it’s about having efficient movement.

I think we will all recognise when we see someone who is supple (or at least have a pretty good idea) but we also need to explore some of the barriers to being able to develop suppleness that will actually transfer where it counts…on the pitch, field, court or track!

Let us not forget that one of the key roles of an S&C coach is to develop a complete athlete capable of performing at the highest level they can free from any physical limitation. While the basis of a Strength & Conditioning Coach’s remit is to develop biomotor abilities such as Strength, Speed and Stamina these can only be built on a foundation of efficient movement.

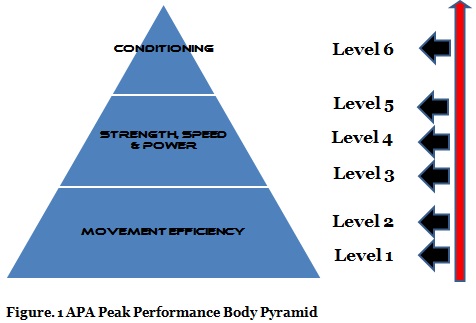

The majority of the time spent in the first few years of an athlete’s S&C programme is spent in developing movement efficiency. I want to start with what I call the ‘key players’ when it comes to movement efficiency. If we look at the APA Peak Performance Body then our logical start point is suppleness because this will have the greatest impact on movement efficiency.

Gray Cook in his book ‘Athletic Body in Balance,’ describes efficient movement as ‘action without wasted movement or unnecessary energy expenditure.’ Effective training simply means yielding results.

We aim to make all APA athletes efficient and effective athletes. That means they can perform at the highest level (can run, jump and throw with the best of them) and critically they can do it with apparent ease!!

As an S&C coach you need to know the fundamental factors of consistent high level performance of your sport and put them into an assessment sequence. This is commonly achieved through a fitness test. A lot of coaches call them key performance indicators or KPIs. For example, in tennis we know that explosive leg power and its association with ability to change direction at great speed is a very important factor in determining tennis performance. We have benchmarks for these qualities to see if our athletes are effective. But nearly every ‘elite’ athlete I have ever worked with is capable of achieving the benchmarks that I use to tell me that the athlete is effective. More often the key is to look beyond the fitness test and see how they get the results; that is to say how efficient are they.

It is a progressive journey and if you have already read the APA Philosophy page you will be familiar with the principle of Long-Term Athlete Development.

At APA we have created a 6 Stage Training System which is based on developing the athlete progressively. Please see the Figure below for an overview. This relates to not just Strength but it underpins the principle of how to develop all biomotor abilities

The foundation level is all about developing the movement efficiency of the athlete so that they can move efficiently with the ability to move free from limitation or restriction. This level focuses on ‘Suppleness’ (mobility and stability). We also look at whether the athlete uses well-coordinated effort so that no movement is wasted-known as ‘skill’. I have already talked about the components of Skill in another page- so check it out here for an overview.

What’s the Difference between Mobility and Flexibility?

This is an important differentiation to make; very few people understand the difference – and it is a big one. Flexibility merely refers to range of motion – and, more specifically, passive range of motion as achieved by static stretching. Don’t get me wrong; static stretching has its place, but it won’t take your athleticism to the next level like mobility training will.

The main problem with pure flexibility is that it does not imply stability nor readiness for dynamic tasks. When we move, we need to have something called “mobile-stability.” This basically means that there’s really no use in being able to get to a given range of motion if you can’t stabilize yourself in that position. Believe it or not, excessive passive flexibility without mobility will actually increase the risk of injury! And, even more applicable to the discussion at hand, passive flexibility just doesn’t carry over well to dynamic tasks; just because you do well on the old sit-and-reach test doesn’t mean that you’ll be prepared to dynamically pick up a loose ball and sprint down-court for an easy lay-up, for example. Lastly, extensive research has shown that static stretching before a practice or competition will actually make you slower and weaker; I’m not joking!

Mobility is different from ballistic stretching (mini-bounces at the end of a range of motion), which is a riskier approach that is associated with muscle damage and shortening. It’s a class of drills designed to take your joints through full ranges of motion in a controlled, yet dynamic context. In addition to improving efficiency of movement, mobility (dynamic flexibility) drills are a great way to warm-up for high-intensity exercise like tennis. Light jogging and then static stretching are things of the past!

What is Stability?

While strength can be defined as the ability to produce force or movement, stability is the ability to control force or movement. In most cases stability is a precursor to having strength.

Mobility and stability usually occur naturally. Children do not usually have mobility or flexibility problems. They do however, lack stability. They don’t just lack strength; they lack control. As children move, they develop control through trial and error.

Physical Competencies:

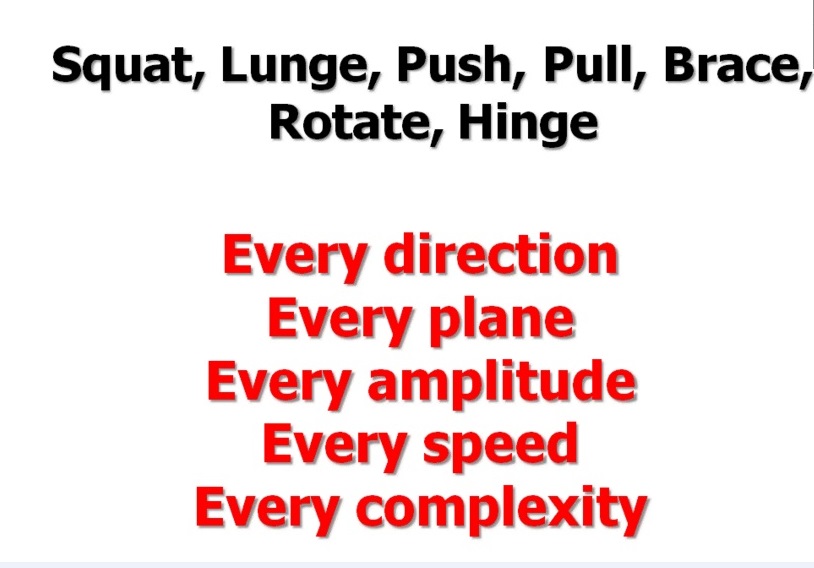

Kudos to Kelvin Giles for blazing the trail up the functional path. Movement efficiency as it relates to Strength Training is about learning how to perform basic movements such as the squat, lunge, hinge, push, pull and brace.

All of these foundation movements will require different degrees of mobility and stability. An athlete must develop sound movement patterns long before worrying about performance enhancement. These movements are not possible in the presence of poor flexibility or poor body control- that is, poor mobility and stability. For example, high level speed training requires maximum range of motion and flawless body awareness. Both of these things are significantly limited when flexibility is limited.

This journey never stops but certainly it is very important that young athletes learn how to do these well firstly without load and then progressively adding load. Part of our Assessment of Suppleness is evaluating athletes on how well they move in these basic patterns, known as a Physical Competency Assessment (PCA). Puberty is a ‘Game Changer’ as this is when we can start to crank up the intensity of the training.

Table 1. APA 6 Stages of Development

|

Girls |

Boys |

||

|

Fundamentals |

Level 1 |

6-8 years old |

5-9 years old |

|

Learn to Train |

Level 2 |

8-10 years old |

9-12 years old |

|

Train to Train |

Level 3 |

10-12 years old |

12-14 years old |

|

Train to Train |

Level 4 |

12-14 years old |

14-16 years old |

|

Train to Compete |

Level 5 |

14-16 years old |

16-18 years old |

|

Train to Win |

Level 6 |

17 years old+ |

19 years old+ |

As you can see, an athlete will spend the majority of their formative years (pre-puberty) in Level 1 and Level 2 learning how to coordinate proper movements.

APA Suppleness development Pathway:

Many of the entry level programmes we use with children focus on the development of stability at key joints such as the knee, pelvis and shoulder. We want all our young athletes to be doing very well on the PCA and a lack of stability around the joints is a key reason why many children do poorly on these tests. Many of the exercises we use to develop stability in these competencies have been popularised as ‘activation’ drills. Below is the progression for core stability.

| Suppleness Focus- Based on Physical Competency Assessments (1-7) | |

|

L1 |

Core foundation: Maintenance of neutral spine during foundation drills that teach proper technique such as plank, bird dog, dead bug and kneeling chop/lift |

|

L2 |

Core endurance: Maintenance of posture for extended period of time (15-30-seconds) with pertubations, resistance and progression to slow eccentrics |

|

L3 |

Core stability: Anti- hip flexion, anti-extension, anti- side flexion, anti-rotation exercises where aim is to keep core stable (resist movement) in presence of forces opposing the movement |

| Level 3 is a key focus of most of the Core Programme for all athletes | |

|

L4 |

Core Strength: Classic abdominal, back and oblique exercises where aim is to create movement at the core in order to produce force. |

|

L5-6 |

Core Power: Classic abdominal, back and oblique exercises where aim is to create movement explosively at the core using resistance such as medicine balls, cables and other weighted implements |

The Table above highlights how the skill of suppleness development progresses as younger athletes move out of the ‘Foundation’ stage and start to train the skills. Level 3 to Level 6 is associated with performance enhancement. We test and train biomotor abilities associated with gross athleticism such as strength and speed. This tells us about how efficient an athlete is at generating power! It’s important to test the skills under conditions of more stress by progressively challenging the body under ever increasing loads.

We will assess the athlete in all areas of the Peak Performance Body Pyramid all of the time but the distribution of time spent training the different qualities will be based on what the assessment shows and the athlete’s stage of development.