What makes a great performer?

Our role at APA as S&C coaches is to create the best all round athletes possible. We do not specialise in just a single method of training as some other companies do (Parisi Speed School, West Coast Strength for example). Our niche is creating the best athletes on their field of play. A talking point amongst the coaching staff in recent weeks has been the application of ‘cognitive factors’ in the training environment. There have been arguments for and against and we will discuss this topic in today’s blog.

Firstly it is important that to create a great athlete, he or she needs many components of fitness, these are a given and widely understood and accomplished, however what separates the top players from the rest is the ability to utilise the physiological adaptations they have accomplished in the performance environment. In order to do this they must be able to perform skilled actions under changeable circumstances, with confidence and in all likelihood on a repetitive basis. How does strength and conditioning training fit into this equation? Surely the most skilful player will be the winner?

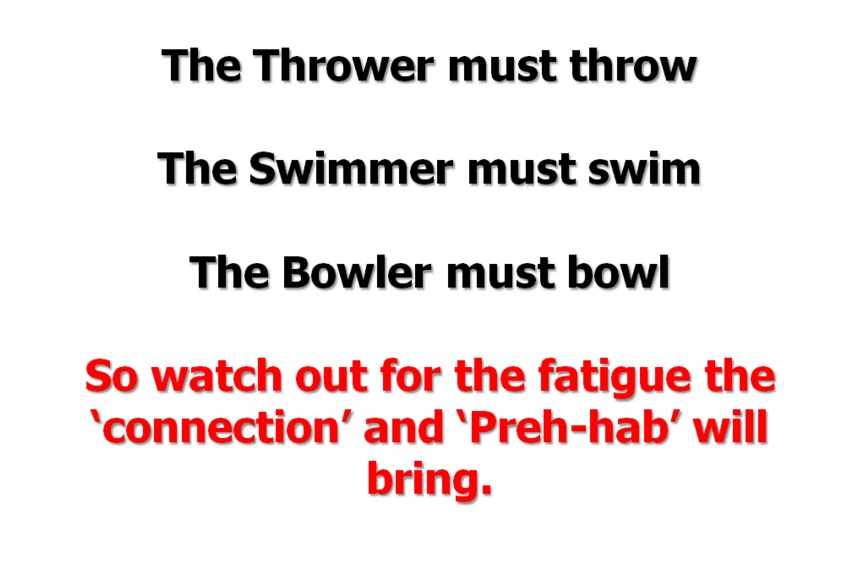

Let’s start with strength training; the aim of strength training is to illicit a physiological adaptation to the muscles to generate a greater force. This force can then be applied to movements such as running, throwing, kicking, punching, tackling etc. In most sports speed is a vital factor to winning. Being stronger makes you faster, therefore strength training and sprinting combined will make you faster (linearly at least). Some sports require the ability to maintain speed over a long time period – the marathon for example – previously trained for as an endurance event in which getting in the mileage was the key factor, nowadays coaches have incorporated speed training into their athletes’ regimes.

This is because the person that wins the marathon is the fastest person over that distance. Long duration events require an increased ability to supply oxygen to the muscles and remove waste products. This ability can be improved through training the body to increase mitochondrial densities or volumes in order to achieve greater oxygen exchange in the muscles. Aside from muscular hypertrophy, neurological adaptations and flexibility/muscle imbalances, these are the main aims of the physiological adaptation process garnered through TRAINING.

In high level sport strength and power levels do not discriminate the more successful athletes

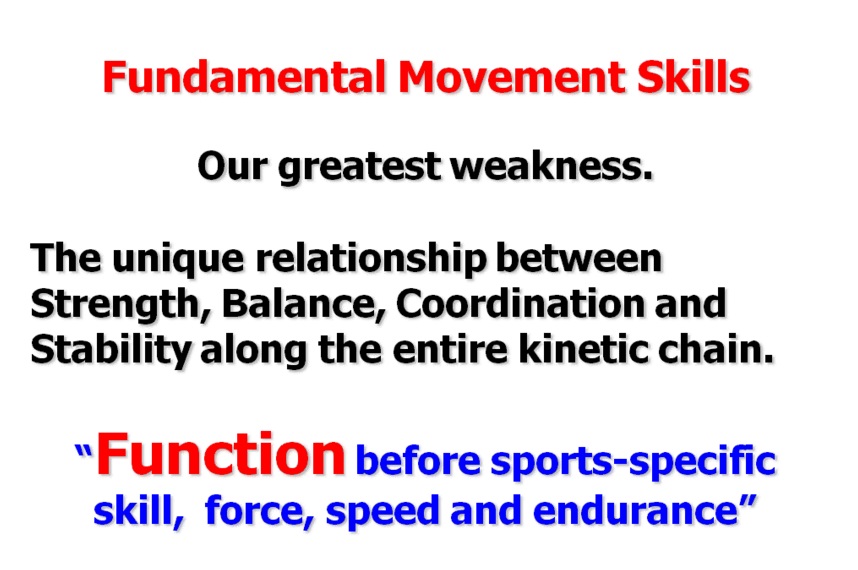

Now let’s look at some other areas that would typically fall under the remit of the S&C coach. Agility, balance, co-ordination, power, reactivity and ultimately winning are all elements that require skill acquisition and cognitive input in great demand alongside the physiological challenge.

”The ability to achieve success at the top level of sports is not decided by strength and power amongst an equal field, but by the ability to transfer skill acquisition into performance (Ives and Shelly, 2003).”

This could be argued that in order to reach the top level of performance, physical prowess is a determining factor; therefore all the top players will have similar physical attributes in terms of strength, power and speed and it is only the level of performing skill based tasks under pressure that creates the ranking in terms of the best performers.

This is where we at APA feel we have the upper hand. Some of training modalities we use with our cohort of tennis players encompass both the physiological challenge and the sport-related cognitive and perceptual demands. This is the environment under which our athletes learn to utilise their physical qualities in a more challenging and competitively stimulated situation. Research has shown that training is more effective in a cognitively stimulated environment (Ives and Shelly, 2003).

Value of practice and training

Ives and Shelly (2003), discuss the difference between what is called a practice session and what is called a training session. Growing up I played football and would attend ‘football training’, I learnt to pass, head, shoot, tackle etc and did some physical development, but not much (maybe because the level wasn’t that high). This environment could be considered a PRACTICE environment rather than a training environment as the key focus is on improving movement techniques, strategies and the mental skills needed for peak performance. Since then, when I joined university I became part of the American Football team and would attend ‘practice’ 2-3 times a week. Seeing as this was a new sport to me with a new set of demands and skills to learn the key to becoming successful at it was repetition of learned skills – in other words practising.

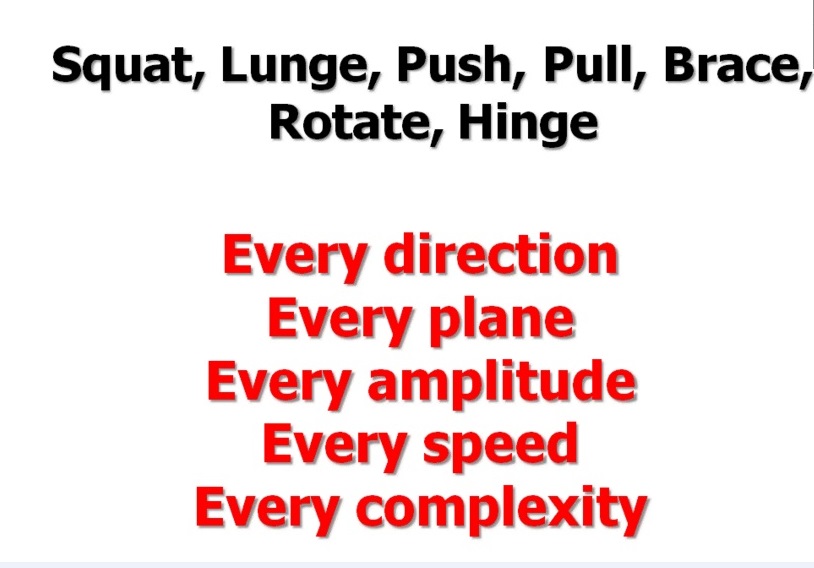

Around this time I also began my journey into strength training, much like many of the young athletes I coach nowadays, I had to learn how to squat, lunge, push, pull, twist, Olympic lift properly before I could begin to train these movements. Because I had a background in being strong – manual labour work around the house when growing up – once I had learnt the skill of the exercise I was able to develop my training ability in that skill quickly. Because of this I was able to become highly skilled and adept at the game, whilst continuing to improve my physical ability and it enabled me to win many matches and championships. This highlights the point that learning skills (again at a young age by preference) can lead to becoming adept in training by subsequently preparing for improving physiological adaptations during later training.

But ‘training’ also needs to have a cognitive component right?

Otherwise we are just going through the motions? Now clearly not all physiological systems training should be done as cognitive training. For example, hypertrophy training requires a protocol different from the one used to train the neural coordination system. Hypertrophy training may constrain movement exploration, yet may promote certain muscle adaptations, like increasing muscle size, that are building blocks to functional performance.

But if we can assume that since this blog is more about making physiological tasks have a cognitive component we need to consider the point that performing skills (even in the weight room) needs to be mindful. This can be achieved obviously with heavy loading which require maximal intent but what about sub-maximal loads? How do we cultivate and accelerate mental effort to tap into that cognitive component??

Functional Training

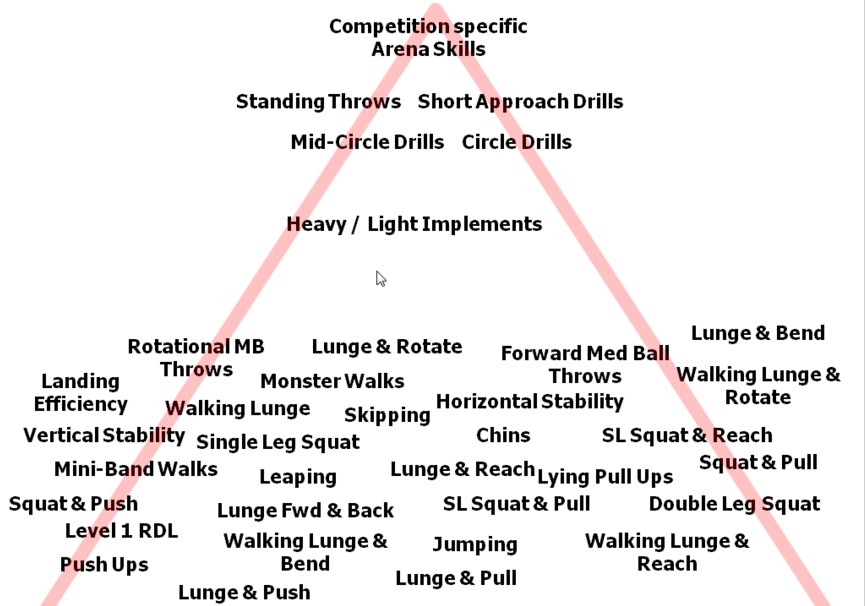

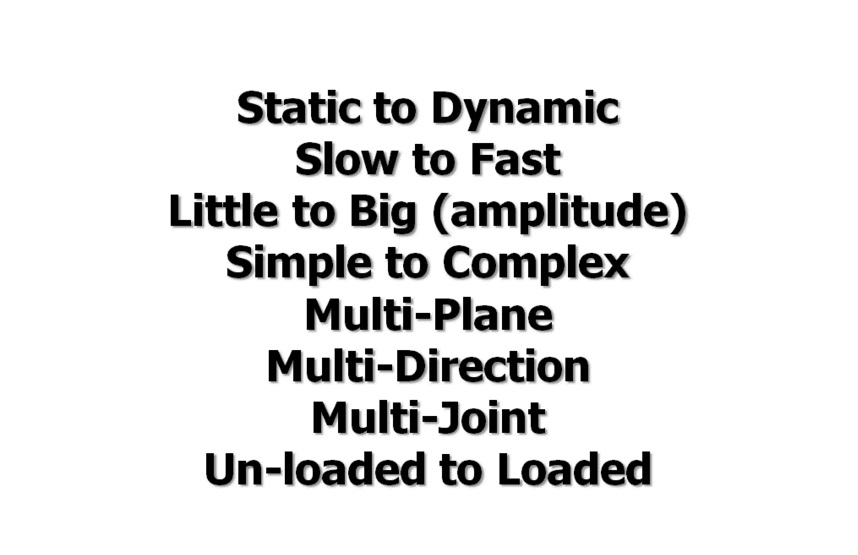

The recent burst in ‘functional’ training – training to meet the demands of the environment and placing the athlete in a mentally challenging environment to illicit cognitive interaction and greater learning and transfer of skills can and has been successfully utilised in sports training. Vern Gambetta brought this into the gym domain with a message to make movements integrated, multi-directional and proprioceptively enriched. This should be applied to all training including strength and power training but so far it has mostly been applied to a lot of single leg balance challenges that are more suited to being a part of a circus act than an exercise that will actually improve performance.

So why don’t we make strength training more ‘functional’ or is the action of gaining strength ‘functional’ by its own definition as it assists in improved performance? A further question still remains, if additional cognitive training can be beneficial in the strength training environment where the stimuli of lifting increasingly more demanding loads or speeds of movement is the skill in itself. Is there further need for ‘stress’ to placed in the strength training environment?

To help us answer these questions we can draw on a journal article by Ives and Shelley (2003) who discuss the following key points:

1. Overall need for a cognitive or perceptual environment- sport related perceptual challenges

2. Specifically the need to put cognitive challenges in a functional strength-power programme

3. A need for a Strategy based around: directed mental effort, attention and intention

I will focus on the components of the Strategy for creating a greater cognitive environment in the weights room, which goes beyond the traditional application of ‘functional training,’ which typically involves balance tasks that look like circus tricks. While these unquestionably challenge proprioception they are not necessarily preparing the athlete for their sports. So what does?

MENTAL EFFORT: The challenge

I think we first need to say that we need to direct our mental effort to something, whether that be getting ‘psyched up’ for a maximal effort or directing that effort to the ‘challenge’ of the task. Basically, we want our athletes to be ENGAGED by the task, whether that be a maximal effort, or a really difficult challenge in some other way. Sports related skills are what excite the athlete so we need to find ways to tap into that sort of feeling in the gym with engaging tasks! What makes sport so compelling is the competitive element, the chaos and the constant mental stimulation and decision making!! Running after a ball or chasing an opponent have clear outcomes and things to attend to so we need to learn from the sports domain and bring that into the gym.

INTENT: Outcome

I think we need to say here that it is important that the athlete is clear on what they are trying to accomplish. What do you want them to be able to do? In tennis this is obvious, get behind the ball and beat the bounce; it’s especially important to have the right intent in that situation because intent drives visual focus!!! But what about in the gym?? I think of the typical intent we say to athletes in the gym that ALL reps need to have an explosive intent on the concentric phase no matter how heavy the weight.

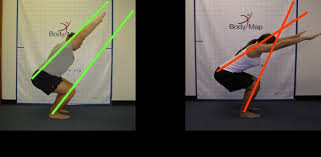

The same exercises done with different intentions – maximal speed, force or accuracy – can lead to markedly different outcomes in neuromuscular control and movements. This is where strength training and cognitive training can have the biggest cross-over; getting athletes to practice having different intents in force production, speed, or accuracy which will lead to greater improvements in performance.

Weight room example

Our coaching commands and instructions are important here. How about simply telling them, ‘beat your best time or performance’, or a asking them to try and win in a good old fashioned race against your peers. Or how about aiming for a specific height on a jump or power output on a lift, or to achieve a specific number of reps in a row without stopping etc (e.g 10 skips in a row). But the best type of instruction is the one which is really open to the interpretation and imagination of the athlete, such as:

‘

Get through this obstacle course as quick as you can’, and in the weights room it could be, ‘I want you to find a way to get up off the floor while keeping your left arm straight- Turkish get up.

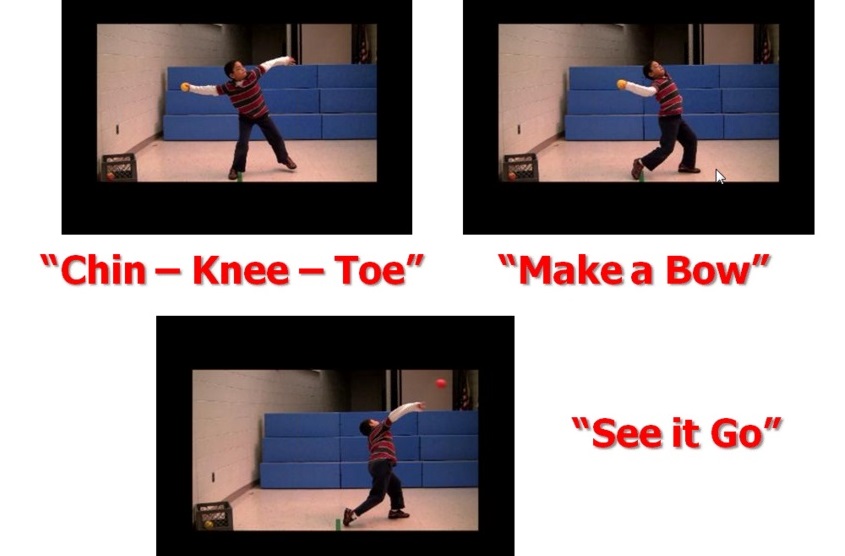

ATTENTION: Process

To me the key thing Ives and Shelley are saying here is the need to develop a ‘non-awareness’ strategy. We don’t want the athlete to pay attention on the task while it is in progress. [Note: this may not be applied across all exercises and session but we are offering it to the reader as a tool to accelerate learning where appropriate]

Focus from the athlete will typically be internalised and given to feelings of range of motion, control of the load, bracing, breathing and alignment. However it has been argued (Wulf et al., 2000) that internalised focus results in poorer learning of motor skills and that external focus should be given to cues, equipment (e.g., golf club) or movement effect (where the ball goes). Similarly Ives and Shelley (2003) advocate against athletes focusing on themselves – i.e. looking in a mirror – but would rather have mental effort directed towards strategies and cues relevant to sports specific performance.

How about paying attention to the bar path in a clean, or the benefit of just giving the athlete the cue of sit down on to the box and stand up on a squat to focus their attention on the box rather than themselves????

In a later section we will talk about the use of sports skills being incorporated with the physical task to really help with this movement non-awareness!

Movement Variability

When the athlete has more variability they learn more adaptability and in the end the skill is more robust. When athletes are free to generate their own movement solutions during practice they learn more adaptability when faced with novel performance situations, which may be particularly important for higher-level performers. As such, functional training within an appropriate psychophysical environment provides a setting to exploit movement variability as a mechanism to enhance an athlete’s adaptability, creativity, and spontaneity— all of which can be argued to be hallmarks of the best performances in sport.”

DISCOVERY-LEARNING PARADIGM

Now we have introduced the need for directed mental effort, attention, intent and movement variability we can introduce the application of these aspects into a coaching framework involving discovery learning.

Discovery Learning is about learners solving for themselves how and what movements to make given the SITUATIONAL CONSTRAINTS imposed upon them. We will discover below that the constraints are key aspects we can control to influence the performance of the task. This becomes especially important when we are dealing with more advanced learners whose skilled are more developed.

In the case of working with beginners or any situation when we are introducing a new skill to an athlete we could look at giving minimal coaching technical feedback and simply letting the athlete come up with the solution. They will bring their own inherent variability to the party because they are learning to coordinate their body.

Ives and Shelvey (2003) say:

”To illustrate for functional training, we suggest that athletes not be told to perform weight training exercises with specific techniques. The athlete, within the bounds of safety, should be free to explore the exercises and become aware of their own movement effects and perceptual outcomes. Rigorously defining ‘proper’ form and the use of mechanical stabilization and anti cheating aids excessively constrain athletes’ exploration and problem-solving movements, and bear little resemblance to that which occurs during athletic performances. With no instruction, however, the athlete may search endlessly for a proper movement solution.

Athletes may learn poor movements and adopt bad habits. The coach or trainer can guide the athlete by providing purposeful intent, ideas about where to focus attention, and clues to key perceptual cues. In this fashion, athletes are able to resolve problems and begin to understand the nature of movement on their own, and determine optimal solutions for themselves.”

In summary we can view the role of the coach as guiding the athlete to optimal performance through giving them a clear instruction on the intent we are looking for, and a few attentional cues BUT letting them solve the movement problem!

Working with more Advanced athletes

Now for more advanced athletes where a basic motor pattern is already learnt and there is less variability in the skill then there is a danger that the athlete can get stuck in the motions of doing the reps with less engagement. Here we can introduce the next level of complexity by building in constraints to re-introduce movement variability that was previously now not present.

Weight room example

SKILL: clean and press

INTENT: I want you to lift that weight from the floor to above your head with your arms straight, 10 times.

ATTENTION: keep the bar close to your body

CONSTRAINTS: (Environmental) Use of different equipment- barbell, kettlebell, sandbag, single arm, double arm etc, jump onto a box, land in a split stance.

So we’ve already seen above that playing around with the equipment and foot position etc can introduce some nice constraints to challenge the movement. But there’s one obvious thing we can do to introduce more movement variability!

Combining a physiological task with a sports skill

I just wanted to finish by giving another example of how a coach can enhance learning through introduction of constraints: This is perhaps the best way to enhance the specificity of physiological adaptations.

Using the volleyball spike as an example we can all see how a rebound jump might enhance jumping related performance in volley ball. But hopefully by now we can see how just doing a rebound jump could be missing a few important cognitive pieces. By being smart we can also do it in conditions of variable practice by manipulating the environmental and task CONSTRAINTS.

Remember how I said earlier that Tennis players get excited about hitting balls, well volley ball players like to spike volleyballs. [The caveat is that they have some basic jumping technique]. But if you put their focus on the skill of the spike a ball then the rebound jump is a means to an end rather than an end unto itself. Basically what I’m saying is jumping from one box doesn’t excite the athlete and won’t get the intent you want as much as throwing a ball in the air and making them spike it as you jump off the floor from the box!!!

This will create movement variability because the type of ball will vary.

Example

Intent: A successful ball spike (rather than an outcome of jump height as a means to an end)

Attention: Placed on the ball and the setter (not on the ground!!!!!)

Constraints: Can put a net in the way, can put other team mates around as well as blockers on the other side.

Note: if the skill of jumping from the box is compromised because of the increasing number of constraints then remove them until the skill can be executed safely, But, THE OBJECTIVE IS TO CHALLENGE THE SKILL and create an acceptable amount of movement variability without compromising joint mechanics at all during the landing.

I hope that has given you some food for thought and will challenge you to keep your weight room sessions challenging and engaging!!!

Fabrizio Gargiulo with contributions from Daz Drake

References

Ives, J.C. and Shelley, G.A., (2003). Psychophysics in Functional Strength and Power

Training: Review and Implementation Framework Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research,

Wulf, G., N.H. McNevin, T. Fuchs, F. Ritter and T. Toole, (2000). Attentional focus in complex skill learning. Res. Q. Exercise. Sport 71:229–239.