Pacey Performance Podcast REVIEW- Episode 367 Gareth Sandford

This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 367 – Gareth Sandford

Gareth Sandford

Researcher and physiologist for Athletics Canada, working with the Canadian Sports Institute, and the University of British Columbia.

Background:

Gareth Sandford

He previously earned his master’s in Sport Science and Physiology, where he did a year’s placement at Chelsea Football Club. He has also coached in the UK, US and in a tribal community in India.

? Listen to the full episode with Gareth Sandford here

Discussion topics:

What is the Anaerobic Speed Reserve and Why Would You Use It?

”Signal vs. Noise Principle- what question are we trying to answer? What decision do I want to try and make at the end? I want a test with high signal and low noise, so if I want to measure aerobic fitness and I include a COD in that test (which includes an acceleration and a deceleration), or if I include a rest period……which has an implication for different recovery kinetics between individuals both from a ventilation/breathing side of things but also what is going on in the muscle.

Every time I add another one of these factors to the test I am creating more noise and so the thing I originally wanted to look at and make a decision about, which was aerobic fitness, I’m now adding more and more variables to. So, when I re-test did they improve because their COD was better, meaning they were better at accelerating and/or decelerating, or is it better because we got some peripheral adaptation and the muscle can better recover from that high intensity effort? Or is it because the training we did aerobically worked and we got fitter from that? And if we are honest, I can’t answer that question clearly. Now I understand there is this tension between sport specific nature of a test and sport specific training. But when it comes to sport specific testing I think you need to think about what are you trying to make a decision about?

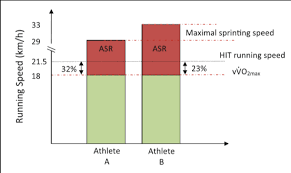

I use a 50-m sprint (MSS) vs 6-minute trial (MAS). The Anaerobic Speed Reserve is the difference between maximal sprinting speed (MSS) and running speed at VO2max”

What is the Critical Speed?

”Critical speed – is the last intensity where the body (from a fuel perspective) is primarily relying almost exclusively on the aerobic system to deliver that performance and in a highly trained endurance athlete (middle distance runner, 10K runner) you could sustain that intensity for 40-60 minutes, so for things like the half marathon, the 10k, marathon these are really important central variables to training and improving aerobic fitness. The reason that is important is because if you can raise that intensity, it essentially delays the chaos that goes on at a muscle level at a harder intensity. So a big aim of training is to raise that speed, and push that further and then build out from that speed your durability at that pace. So that’s one of the big aims with endurance training.

The challenge with implementing critical speed TESTING with runners is that a critical speed model requires a 2-3 minute all out effort and an all 12-minute effort. To use that test you are blowing a hole in someone’s training week. For the 2- and 12-minute scenario there are maybe, I’m going to say, less than 5 world class runners who could run you a reliable 2-minute and 12-minute all out effort; people like Laura Muir who are strong at 800m, 1500m, 3k, 5k. Therefore, the testing of critical speed is very challenging so what I tend to do is use a 6-minute trial (which might equate to about a 2k time trial).

Critical speed (or the lactate threshold- which is approximately, not exactly, similar to critical speed or the second inflection on a lactate curve) you would get that typically in an endurance athlete at 85-93% MAS. So, in a team sport athlete where the durability of those paces is not going to be as high, because it is not such an important training aim, that percentage is going to be slightly lower, probably in the 75-80% range, but what that also means is, there is some head room to push that up. So, when we are doing testing with our team sport athletes for aerobic purposes yes MAS is the thing we measure but we are using that for two purposes. 1- to prescribe sessions around MAS but also 2- to understand where approximately that critical speed is going to sit underneath it. And then we can use both of those as training zone stimulus with our athletes.”

What are the types of models that you can use in developing athletes with aerobic qualities like footballers?

”When you put a sub-group lens on top of that and look at the more endurance-based athletes within your group, the critical speed particularly, is like bread and butter for those guys. So someone like a Jordan Henderson or a James Millner, very different type of athlete to a Raheem Stirling. If you gave Raheem lots of long efforts at critical speed that would break someone like that; it’s too much of a stimulus from a number of angles. But for your more aerobic run all day type athlete that kind of stuff is really going to maximise the aerobic qualities they have. Whereas the more speed endurance, harder anaerobic stuff probably flattens them a bit (they don’t have the same glycolytic capability at a muscle level to cope with that). If you look at it from a muscle physiology perspective, if they are more slow twitch as an athlete their muscle machinery is built to work more aerobically, that’s their preference. So, you want to maximise that type of system in that type of athlete.

If you take Raheem the principle of critical speed is still important because there is a minimum aerobic demand to be able to handle 90 minutes 3 times a week. The question is how do you get there? The principle is still important, but you get there differently. This is where moving back from going ‘’here’s my training model, and going [instead] who have I got in front of me?’’ You can then be more specific in how you apply that critical speed principle to that speed-based athlete.

So someone with a speed based profile, who would probably have a slightly lower MAS and a very fast maximal sprinting speed, around 10 m/s sprinting speed (what I would consider a speed type athlete for team sport or middle distance endurance athlete). A more endurance-based athlete might be a bit lower on sprinting speed around 9 m/s but would have a very high MAS (so smaller speed reserve).

So the repeated speed or interval based approach is how I would tackle developing those aerobic qualities in those speed based athletes. There a few reasons for this; the research says that to build aerobic fitness you have to accumulate time at VO2 max. But the challenge is with that, if you are metabolically more fast twitch things become very anaerobic very, very quickly. And so the stimulus that was intended to be primarily aerobic actually isn’t. There are recovery and enjoyment implications of that and you just can’t get the type of volume you want to maximise that stimulus, and instead it tends to flatten and overcook people.

Repeated sprint or Interval based training allows you to run at a faster speed which is more mechanically in their wheelhouse. You can cap the amount of anaerobic based stimulus that is generating by duration of the repetition. Perceived exertion can be really high and very uncomfortable if they do a traditional plod. With intervals, you’re not looking to get faster, you’re just looking to build volume. As an example, 200m at 16-sec pace- let’s say calculate these speeds based of MAS and critical speed as an estimate and looking to build up the volume by the number of those reps you can do.

Now the more endurance- based runners I would actually consider taking a leaf out of some of the more middle-distance running philosophy and doing more tempo runs which is a workout that is in around that critical speed landmark, starting at the 6–8-minute repetition range length and build that out, progressing up to 20-30 min with a highly highly trained athlete (10 years training at 30 yrs old). So, I would be looking at how I could sneak that into my training week.”

What is Tempo running and what are the ways in which a coach can use it successfully to train his or her athletes?

”Jessica Enis case study: How do you build the endurance aspect of the 800 m race for example without taking away from the speed-based events (high jump, hurdles etc). It’s the same question middle distance and team sport coaches are asking. What they did was every day for a warm-up, Jess would do some kind of plodding jog. She didn’t particularly enjoy it but it was her warm-up. What they did over time was pick up the pace of that a little bit so that actually it was nearer the critical speed type effort, and they started with 2 mins, and then 3 and then 5-mins and all of a sudden across a week they accumulated up to 20-35 mins of work at critical speed. So micro-dosing it like that over time compounds and builds aerobic adaptation. So when you retest and you look at where MAS is you can judge those sessions of critical speed based on how someone is breathing. When we test that pace in the field and I’m listening to their breathing, If breathing is sounding like it is getting out on control then they are working too hard because they have moved beyond that sustainable pace.”

‘

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Signal vs. Noise Principle- I want a test with high signal and low noise.

- The Anaerobic Speed Reserve is the difference between maximal sprinting speed (MSS) and running speed at VO2max

- Critical speed – is the last intensity where the body (from a fuel perspective) is primarily relying almost exclusively on the aerobic system to deliver that performance.

- Know your athlete – repeated speed or interval based approach better way to develop aerobic qualities in speed based athletes.

- Tempo runs – used as part of a warm-up can be useful way to micro-dose time spent at critical speed pace.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

Twitter:

@Gareth_Sandford

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM