Long term speed progressions for the youth athlete

Hi Guys,

I hope we are all doing well and wishing everybody a safe return back into sport. Today’s blog is about a topic which I think over frequently, speed training! How do we get our young athletes faster? So they can dominate their opponents and what are the different ways we can achieve this? Speed kills and today I wanted to share a few insights into the long term speed progressions for the youth athlete. The way speed is expressed will vary in different sports a needs analysis will determine this. Today I will cover long term speed progressions in more general sense. Topics today will include:

What do we mean by the term ‘speed’?

Factors affecting speed?

Trainability of Speed?

Strength and its relation to speed in youth

Practical implications for training speed in the youth athlete

What do we mean by the term speed?

In physics Speed is a scalar quantity of time between two points. Speed can be further broken down into the three components that place varying demands on central nervous and muscular system.

- Reaction time, which is the speed that the athlete responds to an external stimulus

- Ground contact time, amount of time foot spends in contact with the floor

- Cyclic movement frequency, the number of repetitions in a given time frame

Noticeably, Reaction time is an expression of the nervous system, whilst ground contact time and cyclic movement frequency is expressed through the muscular system. Often, young athletes will try to express their speed through cyclic movement frequency i.e. moving their feet faster, to them it feels faster due to more frequent leg turnover. However, this does not mean they are covering more distance.

Trainability of speed?

Nurture or nature? An archaic argument amongst people. Is Speed a trainable quality? Or are certain individuals just gifted? Speed is considered the least trainable in relation to endurance or strength qualities however, this does not mean it is untrainable. In addition ingraining the foundations and optimal speed mechanics, will enable young athletes to realise their speed potential into their adulthood. Top athletes seem to utilise their speed potential better as they become experts in qualities such as coordination, strength and endurance. Now I am not saying everyone has the ability to become elite level sprinters! But, we can certainly unveil individual speed potential by teaching relevant speed mechanics and consistently running fast!

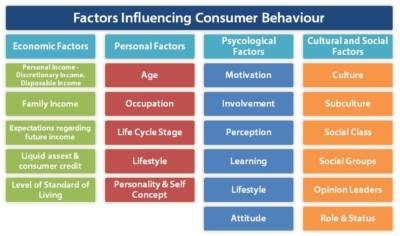

Factors influencing speed

Developing speed solely through physical means is debatable. Whilst the physical development of speed has huge importance, the question can remain whether it is a speed, movement issue or technical issue. For example reading the game well, anticipating the opponent’s shot or accelerating efficiently in awkward positions. Although, what I am about to set out next is mainly in relation to footwork patterns in tennis, I quite like the four performance factors, in developing speed by APA. I think we can apply some of the subcomponents when describing factors influencing speed, I have written these in the forms of questions I ask myself:

- Technical– Do they possess the intermuscular coordination to move efficiently, and the ability to position themselves on the pitch/court optimally to execute their action?

- Tactical– Are they in the right position? In team sports this could be the right position on the pitch or court?

- Physical– Do they have enough explosive strength to produce high levels of force quickly? Do they have sufficient fitness levels to reproduce this?

- Mental– Are they mentally focussed? Reading the game well?

Although this may seem like a puzzle to solve it allows us, as a team, to figure out what the issue is and provide potential solutions. It takes skill to really understand the problem, before implementing an intervention.

Strength and its relationship to speed in youth

How strong is strong enough? Whilst a lot of coaches have their own ideas on what the numbers dictate, I would argue that this number is very individual and depends on the athlete’s level. With regard to developing athletes, strength training can have a large, positive influence on speed due to factors such as increased stiffness and force output. Here is an interesting quote from the guys at ALTIS:

“Strength improvements occur naturally in the general population at a high rate up to their late teens to early 20s. Hence, from a long-term development perspective it is wise to start strength training (maximum strength development) when the rate of natural strength improvement begins to slow down and stagnate. Using this strategy offers the opportunity to continue to improve the sprint performance through new training means, and beat the natural stagnation of speed that occurs in late teen”.

Interesting insight, however it is acknowledged that lighter loads at a younger age is beneficial for technique development and working on the speed end of the force-velocity curve. Importantly, teaching the developing athlete to produce force quickly (explosive strength) and intent, carries significance when considering a long term progression. Moreover, the word intent is key, if an individual is simply not trying hard enough, we may not get the physical and psychomotor adaptations we desire.

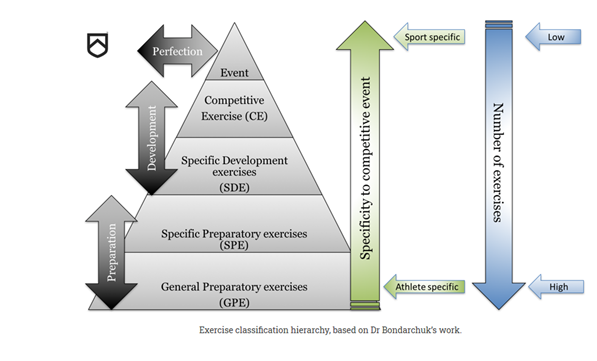

Practical implications for training speed in the youth athlete

I want to finish this short blog by suggesting six of my practical ideas when considering long-term speed progressions for the youth athlete.

- I would suggest that in the early stages, a large proportion of time is spent on acceleration.

- Keep coaching cues simple, try not to overload the youngster with too much information, I like to use the power of three, no more than three work-ons at a time.

- Using a game based model is great for that particular theme, creating competition and the subsequent intent. Using games/activity scenarios also develops optical and acoustic reaction ability.

- Sprinting in multi-directions from a variety of start positions to give the young athlete variety and the tools to react and execute to their sports varying demands.

- Use a variety of drills to reduce repetitive strain injuries particularly with athletes reaching peak height velocity

- In developing athletes strength training can develop characteristics including technique development, intent and intramuscular coordination.

Thanks for reading!

Konrad McKenzie

Strength and Conditioning Coach

P.s. We are taking a short break next week. We will be back the week after and look forward to supplying you with more useful content! Thank you, for your continued support of this blog.

Follow Konrad: @konrad_mcken

Follow Daz: @apacoachdaz

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM