Pacey Performance Podcast Review – Episode 413 Marco Altini

This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 413 – Marco Altini

Marco Altini

Marco is a Scientist and Owner of HRV4Training. In addition to this, Marco is also an advisor to Oura Ring.

Background

Marco has a mixed background between computer science and sport science. He has degree in computer science & engineering, a PhD in Data science and another Masters in sport science. He has a role as a guest lecturer in a University in Amsterdam.

🔉 Listen to the full episode with Marco Altini here

Discussion topics:

”Is coding, is learning aspects of computer science the next thing and how far are we along the road of the computer science and sport science getting closer together?”

”We are getting there. Not for everyone, but for some people I think it can be a new path to explore and something where you can start to play with all the data that are taken from the different devices now fairly present in professional environments and even at lower levels to use that information and help the team in different ways.

We teach a course here at the University which is exactly that, data science for sport scientists so the basics of how to process the data and machine learning and building models and evaluating the accuracy. I think that can be something interesting for sport scientists but again it doesn’t necessarily have to be what everyone should be doing but I think if some people start doing that I also think it helps the whole industry to have a better approach and more critical thinking around these solutions that are otherwise given to you and they are difficult to interpret if you don’t really understand how they work.”

”What is HRV and why should we be bothered about it?”

”HRV stands for Heart Rate Variability and it refers to the fact that the heart does not beat at a constant frequency there is always some variation between consecutive beats; and this variation is not random, it is actually caused by how the autonomic nervous system (ANS) modulates heart rhythm.

And since the ANS is changing its activity in response to stressors, measuring HRV becomes a way to capture our response to stress, so in short it is just a proxy for stress that is non invasive and easy to measure (such as hormonal changes which are harder to measure, and more expensive). We cannot measure the ANS directly either, we can only measures what the ANS influences that is Heart rhythm and that is why eventually we look at HRV because it becomes a proxy of these stressors.”

”What are the different ways we can measure HRV?”

Chest strap

”We can measure it traditionally using an electrocardiogram (ECG) which measures the electrical activity of the heart and that is the same technology you have today in a chest strap, so if you use an app that allows you to link to a strap with a sensor like Polar or Garmen then you are are measuring the electrical activity of your heart, and from the beat to beat differences you can compute your HRV.

Optical Methods

An alternative is with optical methods where there has been a lot of work for example an Oura ring or a Whoop device that you wear on your finger or on your wrist and they are measuring changes in blood volume. Of course the blood is flowing when the heart is beating so there is a very strong link between activity that you measure at the heart and the activity that you measure somewhere else.

At HRV4Training we use just the phone camera so you don’t need any sensor- the technology is the same because instead of having a dedicated sensor, we use a flash. The sensor would normally flash a green light or an infrared light so you can’t see it (but it’s there) then you have another receptor, an LED, that is capturing the reflection of the light so you can see these changes in blood volume. If you use a phone, it’s a similar story but the light source is the flash and you capture changes taking a video with the phone camera.

There is a caveat that not every device is equipped for this task as most devices are not. They need to be designed for this purpose, where as most are designed to measure heart rate and that makes the data sometimes not usable for HRV.”

”What would make optimal measuring conditions and maybe give some team sport context for that coach who is working with multiple athletes?”

”So first of all we need to contextualise what we are interested in measuring. We talk about HRV as a measure of stress and it is not really specific to a particular form of stress but it is very sensitive to all forms of stress. So that is why it can be useful because it can give us an idea of the response of the athlete to not only training but other forms of stress that they might be experiencing such as:

- International travel

- Illness

- Intake of alcohol

- Any sort of thing that impacts your ability to train and perform

Now if you want to look at this overall marker we cannot measure at any random time of the day or the night because the ANS is always continuously adjusting depending on the things we do. A lot of these adjustments are transitory and irrelevant for our application of interest, which is to quantify this overall stress.

So to quantify this ”baseline” stress level that results from the most impactful stressors and not just from any useless transition like having coffee or eating something, or walking up the stairs. We don’t care about those changes, we care about your state at rest as a result of the past few days of cumulative stressors and the strong ones that have really affected you.

Now to get a snapshot of that we have really two moments when we can take a measurement that are not impacted by all these other transitory stressors. These two moments would be either we measure:

- During the entire night or

- First thing in the morning when you wake up

If you use a device that looks at the night it is important it is the entire night or at least 4-5 hours because if you look for just a few minutes (like the Apple watch- which provides a few data points during the night) they are all over the place because the ANS activity is tightly coupled with the sleep stages, for example, and sleep stages happen on any given night at different times. So using a few data points it may be that the device is sampling when you are in deep sleep and another night you are in REM sleep, and there is going to be a very large difference and it has nothing to do with your baseline stress level, just the fact that you were in a different sleep stage.

Both Oura and Whoop provide the average of the night and provide the same data because they are using the same technique.

It is also important to be consistent and use only one time of day – you can’t use night during some days and morning other days. Also some athletes may forget if you tell them to take a measurement in the morning. Another consideration when working with teams is if you measure in the morning then you are measuring after the restorative effect of sleep and after the stressors have happened.

Night vs day measurements

If you are a team and you played a match in the evening then the overnight data will be more impacted by the game simply because it is earlier so it is likely that it will show a suppression, it does not mean that you have not recovered (in the morning) just that you are measuring very close to the source of stress. So the interpretation of the data needs to account for when you are measuring. So you can wait another day and see if things go back to normal and then you have nothing to worry about.

One thing is to talk about the raw data and HRV and make sure it is accurate and another thing is to look at readiness and recovery scores that are built on top of that, how that information is used and there indeed the discrepancies are obvious.

A good way to look at the wearables in general is to look at the metrics and see which ones they agree on and in which ones they don’t. The ones in which they agree are typically the ones you can rely on. So if you look at heart rate, HRV and temperature you will see they are very similar across devices but if you look at sleep stages, or readiness or recovery then they are all over the place!

Intensity of Training

The response to high intensity training will be a much higher suppression of HRV. The intensity will drive much of the change sometimes more than the volume. The menstral cycle is an important factor as you have variations that are linked to the changes in hormones. So if you have a reduction in HRV during the second phase of the cycle (accompanied by a slight increase in heart rate) that is quite typical and so that suppression is linked to something you are expecting, and so you don’t associate it with something else. Therefore you don’t attribute the change to something like a poor response to training. But the variability between women but also within the same person (across cycles) is so high that the HRV is not very easy to track the menstrual cycle that way but we must keep the cycle in mind.

Interpretation of the Data

You should collect data for a while in order to build the ”normal range” which is the range of values in which your data will be if there are no abnormal stressors and things are going well. The normal range is somewhere between one to two months. The baseline change is the weekly moving average so it is the weekly value with respect to the normal range.

At point then it is easy to flag deviations from this normal range so that you can identify potential issues so that is where we have had a data platform built where we can read data from. The night devices should also have the same as we feel we should be looking at the physiology and the response rather than building scores that confound that information.

If you have a suppression in HRV but on the day the athlete subjectively reports that they feel great then we don’t have such a reactive approach and do not change anything, and then we wait for the second day. If on the second day everything bounces back to normal, great. We haven’t done anything. If we have two or three days of suppression then at that point the baseline and the 7 day moving average will start to go down, and perhaps the 7 day moving average will go down below the normal range – and then we have a more chronic form of stress. It’s a repeated poor response so that is a good time to start looking at the reason for that change and possibly implement some changes in the programme. This could be manipulating load or prioritising other forms of recovery such as sleep which may have been neglected.

What you want to see, especially in a professional environment, is not these combinations of parameters and variables (readiness and recovery scores) – it is the actual response of the body (HRV) so that is what you should be looking at (the raw data and the physiology) but still be able to contextualise it with respect to an athlete’s normal, otherwise if there is a reduction you never know if it is meaningfully lower or it is just a bit lower, and you shouldn’t care because it is just normal day to day variability.

For example, you are doing a training camp so now you are training more and your readiness and recovery scores will penalise them for doing more because the model expects that when you do more you are less recovered. It is just as simple as that. But then that is not the information you care about – you want to see the actual response of the body – so if the HRV let’s say, is still within the normal range, then it means you had a good response to that increased load and that is exactly what you wanted to see.

The physiological data gives you the answer if they are responding well to the load or not

So when you put all this extra information in like sleep and activity level into some of these apps you end up knowing less because if it says your recovery/readiness is less, is it less because your body did not respond well, or was it because your sleep was a bit different or your activity was a bit different. This is not to say that sleep and activity are not important, they are, but they are context to see when there is a change, if it is coming from there or not. But it is not what you should be looking at when you are looking for the response, you should just be looking at the physiology- the HRV and how it responds in response to the stressors and not in combination with other parameters.

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Heart Rate Variability (HRV) – refers to the fact that the heart does not beat at a constant frequency there is always some variation between consecutive beats; and this variation is not random, it is actually caused by how the autonomic nervous system (ANS) modulates heart rhythm.

- Chest straps vs Optical methods – chest strap measures the electrical activity of the heart whereas optimal methods measure blood volume to estimate HRV.

- Time to measure – all night or first thing in the morning when you wake up are the two best times

- Interpretation – it is important to establish a normal range before you start to interpret if the change in HRV was a meaningful change.

- Interpretation – don’t be too reactive to just one day of suppressed HRV. It is better to pay attention to a few days of suppression before making a decision to act.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

Episode 381 Alastair McBurnie & Tom Dos’Santos

Episode 380 Alastair McBurnie & Tom Dos’Santos

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

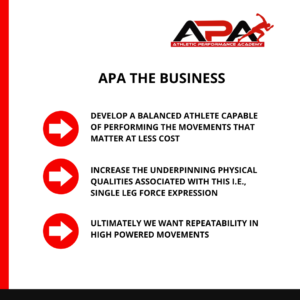

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM