Episode 450 – Tony Blazevich – “Activation” sessions and asymmetries: Are they really that important?

Tony Blazevich

Background

This week on the Pacey Performance Podcast, Rob is speaking to Professor of Biomechanics, Tony Blazevich. The first half of the episode is all about activation sessions. What does “activation” or sometimes called “pre-activation” actually do? Does it do anything? Does it do what we think it does? In the second half of the episode Tony finishes off with a fun chat about sprint mechanics as this was Tony’s area when doing his PhD.

Email: Blazevich@exu.edu.au

🔉 Listen to the full episode here

Discussion topics:

”In terms of biomechanics, and one of the disciplines, I suppose that normally encompasses a sport science degree, is biomechanics the most scary for an S&C coach?”

”Well, I mean, it depends on your background, but I would say, yes. But here’s the thing. I mean, biomechanics is normally first up, also not the favorite of any sports science student. And what I would say is, I nearly failed maths in high school, I really struggled with maths, physics is a whole different kettle of fish. I loved physics, because it made sense. Maths was very abstract. And so I think with biomechanics, if you are taught by someone who really focuses on techniques, technology and the mathematical underpinnings, then it’s going to scare a lot of people who don’t have happy experiences in that realm. But to me, I always thought when I was a sports science student, that I would end up as a physiologist, because after all, isn’t that what they all were?

But actually, as I got further into my degree, I realized that if I don’t know the movement patterns that are required, if I don’t know the forces we have to develop, if I don’t know the ranges of motion I have to move through. And if I don’t know the speeds that I need someone to move at, then how can I possibly set any kind of useful training program? And so I ended up having to move further and further into the biomechanics. And by the time I got to my PhD, my questions were simply, how do we give an optimum strength training program to a sprint runner? And I would already figure out that maybe just imitating or trying to imitate velocity was not really a key, but there are lots of adaptations as we train it in very different velocities. But maybe there’s something about the movement pattern that we need to replicate.

And I really, in my early career got into this idea of understanding how much we need to replicate a movement pattern, or whether just with lots of sports training, we can just give some basic lifts. And of course, the answer is very, very complicated. And the more I learned, the more I realized I never knew at the time, but that meant that I really had to focus on biomechanics. And ever since then, comparing how humans move to birds and cheetah and monkeys or primates, other primates. That kind of biomechanics really informed me and that was when I was over with you guys in the UK, there are people at UCL and King’s College and that who were really on the animal side, and it really opened my eyes to understanding how any organism can actually complete a task. And once we just break everything back and say, “What organism have I got? What is their goal? And what would be an optimum solution to this movement problem?” Then we start to be able to develop plans. And to be honest, it’s just the most enjoyable part of Sport Sciences, if we just stick to sport today is trying to understand a human from that level. So yeah, I would say, get into your biomechanics as much as you possibly can.”

“One thing I want to start with Tony, and I think it’s probably the thing that with time with an athlete, especially on the field, the S&C Coach has relative carte blanche over, and that’s the warmup. Whether you get 20 minutes, whether you get half an hour, whether you get 10 minutes, is the time where the S&C coach can have some sort of influence and a regular influence. Why do we do a warm up in the first place? And then we will get into the intricacies of different phases of the warm up, I suppose, in a second?”

“Yeah, sure. I mean, there are a lot number of reasons we do the warm up. And you have kind of hit on this idea that if you are the S&C expert in sports like football, I know it’s very common that the warm up is sort of that one place where they say, “Right, you are that person you go and lead it and everything else is really up to the coach.” In other sports, of course, rugby, for example, collision sports, S&C coaches usually have a lot more input, including even the technical aspects of, how to hit and all this kind of stuff. But if we do accept that warm up is all you have got, I mean, ultimately, the warm up is there to get the body ready for optimum performance from a physiological perspective. So that’s everything from changing muscle temperature, remember that around about a one-degree increase in muscle temperature can increase the power output by about 5%. So it’s quite a significant effect having a higher muscle temperature, we have got increasing blood flow and getting the aerobic energy system really kicking along to reduce that oxygen debt when we need to then do high intensity exercise, we have got increases in muscle water, which I think a lot of us forget and maybe we are not still sure of exactly what the overall benefit is. But if you have read studies from the 60s and 70s, you will be very convinced that as the muscle draws a bit of water mostly dragged in by lactate ions or molecules, that muscle water increases muscle force production and improves it across the velocity spectrum. So we think that might have a big effect. And, that’s sort of, in addition to the neurological perspective.

The neurological is, of course, if you are talking about an S&C, and only having a certain amount of time and trying to figure out how to make the most of it, I think what most of us talk about is, “Well, how can I use that as a way to ingrain optimal movement patterns? How can I use that as a learning opportunity, because I am doing a warm up in every training session and before every game, instead of just literally warming them up, how can I get more bang for buck?” And that’s where a lot of your listeners will think about using drills or skills to optimize movement patterns, putting in situations specific skills and drills that allow players to learn to pick out and notice patterns of play, which the more you see them, the more you start to get them naturally, that can be done in training, understanding how they can regulate their psychology for optimum levels of arousal that can be done during the warm up so that they can then continue to monitor that throughout whatever their competition game or match is. And so there are lots and lots of things you can achieve in a warm up, if you know how to then put the pieces together.”

“Just going back to the animals and it may come back to the same universities, you never see a cheetah stretching and going to do mobility before they go and sprint and catch prey or whatever it is. That’s obviously a far-fetched comparison. But where does that actually come from? Is there anything there whatsoever?”

“Yeah, I mean, first start with the cat. I mean, cats do stretch, by the way. But they don’t do it just before they hunt maybe, they usually have been stalking and moving before they hunt. So they are moving. But you are absolutely right. I mean, the question there, as we could always ask is, “Well, what if the cheetah could warm up would they have been more successful?” And the answer is, we don’t really know until we do the experiments, right? But if your question is, then seriously, why is it that humans feel the need to do these sort of long, protracted warm ups when every other animal on earth, goes about their daily existence without having to do the warm up? And all I would say is that it seems like at least in humans, and this is the same for most mammals, though, is that when we are sitting at rest, our body is not in an optimum state for movement. If you are about to be chased by another animal, we immediately increase body temperature, we increase sympathetic drive, we increase blood flow, we take all the blood from our internal organs.

But when we are about to play a game of netball, or basketball or run 100 meters, we don’t necessarily have that absolute life and death physiological response. And so we then have to imitate it, then once we try to imitate that to some degree, we then start to say, “Well, what else can we bolt on that would make us absolutely optimum?” Because in the end, when we are trying to win a game by one point or one goal or 1/100 of a second, and so then we start to say, “Well, what else can we do?” And this is where the warm up starts to get longer and more complicated when we really tried to fully optimize human performance. I don’t think we need to do that for every weekend warrior, or everyone who just wants to exercise I think these sort of proper, highly developed warm ups are really optimum for competitive athletes and we are trying to do something pretty extraordinary.”

“Do we need to do activation before a training session for rugby or a training session for football? What is the purpose? What do people think is the purpose?”

“Okay, well, I am probably going to have to give a slightly complicated answer here. Just to allay people’s fears, it is not the case that if I just get a glute band and do some side shuffles, and then 15 minutes later go and warm up fully for my sport and perform in the sport that there is likely to be some sort of major and significant effect on performance. That’s probably not the case. But let me just try to allay everyone’s fears across the whole spectrum here. It could be the case that some motor pattern opportunity is being gained by just practicing a very discrete skill first, and that maybe loading it by adding a band just presents more feedback to the central nervous system to know where the body is in space. The idea that it’s somehow then allowing us to activate the agonist muscle to some degree to get more force, I am not sure it’s true. And I can go into much more detail as to why but the idea that the brain needs to get calibration as to where its movements are in 3D space, could be a reason why those sorts of brief short activation sequences might make people feel like they are doing something well. I would argue that if you actually did a very sports specific, skill specific warm up, we would see that those initial activations are not doing anything at all.

But I just want to remind people, though, that it is the case that you might hear, particularly in the physiotherapy fraternity that these activation exercises are maybe more common than in the sports science fraternity and you wonder why and you think, “Well, maybe it’s because we are trained considerably in exercise, whereas they have to be able to diagnose so they get less time to actually learn about exercise.” But at the same time, remember, physios are there with a lot of people who have pain, a lot of people have been injured for a prolonged period of time. And we can talk about this, it absolutely affects your motor pattern and the way the brain communicates through the spinal cord to the muscles. And so in athletes who are struggling to adopt an optimum motor pattern, it is true that if we spend a very small amount of time deliberately trying to activate a muscle or muscle group at a certain length or at a certain joint angle, and we slowly increase the amount of force reproduced in that joint angle, that over the next minutes or even hours, that specific motor pathway will be highly excited, that it will be a pathway that is easier to send signals through, the possibility then exists in those athletes, that when they then start to do the warm up, they are actually feeling like they are able to hit the appropriate technique better.

Again, I am not saying that, that means that they can all of a sudden activate the muscles so remarkably well. What I am saying is that long term potentiation, by long term, we are talking seconds, minutes, maybe hours. Long term potentiation of a neural pathway literally is a way to allow our brain to activate a very specific action or muscle with less central or descending drive. So I just want to say that whilst I would normally not think that what we tend to see as activation exercises are going to have a significant impact on the majority of athletes, I just want people to take that step back and accept that potentially in some people, there is a reason to do it. And it might then help them further down the track through the warm up and into a game or a match.”

“Why did the glutes get such an emphasis on this because I have been places and people call it glute activation, So why focus there? And I know this is a horrible question. But is that focus necessary?”

“Yeah, I am going to give you my answer. And then I am going to give you that little caveat again. In the majority of people, doing a glute activation exercise is not going to affect the way they then perform a very complicated high velocity task. Okay, so for the majority of people, I have seen no evidence that lying on your back, one leg with your knee very flexed, which just takes your hamstrings off stretch, and trying to activate the glute then affects the way the body works. And I know that there are one or two studies maybe concluding that there is but when I delve into the actual data, I either don’t see that it backs up the conclusion or in fact, I would have taken the opposite conclusion that this actually is indicating that the nervous system is not using it right. So the question then is, “Why is everyone focusing on the glute?”

Well, for a start, if we are talking about running based athletes, it is true that when the hip is relatively flexed, and then generates an extensor moment, the gluteal muscles are very, very important. In that case, gluteus maximus is a really important hip extensor along with the hamstrings. Once the foot is on the ground, you have other gluteal muscles that are really important, minimus medius, as well as tensor fascia latae and a few of your, I will call them just hip rotator muscles a bit like your rotator cuff, you have got like a rotator cuff around the hip. And they are trying to hold the pelvis in the optimum position to allow the hip as the leg swings to store and release elastic energy. And if the hip is falling, that’s energy that we are using to cause rotation. And that’s not energy going into forward propulsion. If the hips are moving like this, then when the thigh moves back, the muscles that are storing elastic energy and not the ones that are then trying to drive the hip flexion once the hip then comes back and corrects itself.

So what we need is for the axial skeleton and the pelvis to be held in very specific body positions, we need a very complicated activation pattern to do it. This requires a lot of the muscles that help to do it, either to extend the hip in the first place, or to hold the pelvis or gluteal muscles, not just glute maximus. And in my experience, I have to admit, I am particularly working in football or in soccer, where you see flattened bums in some athletes, the amount of hip rotation being caused is significant. And when we have then spent eight weeks doing exercises, both the running drills and strength work to get the hip extensors working more effectively, the glutes firing if you like, the running mechanics fix up, and the injuries are moving away. And they are running faster. So I know we don’t like to say, “I want to activate my glute better.” And then people say, “Well, if I couldn’t activate my glute, I couldn’t walk.” And I would say, “Well, I can do a push up, but I can’t bench press 200 kilos.” At the elite level, it could be the case that working a certain motor pathway is very, very useful. And because a lot of us are running athletes, the glute probably caught a lot of that stuff. But look, at the end of the day, the predominant power output is actually coming from your ankle when you run, not from your hip. Your hip obviously does the work that is stored at the ankle. So it’s still absolutely vital. But in lots of other sports and lots of other movement directions. There are many other muscles that need to be activating appropriately for optimum performance. So I am not sure why glute is always specifically targeted. But at the same time, I just want to put in that caveat that in a lot of athletes who aren’t highly trained sprint runners and are doing sports where they are often performing under fatigue and start to get into bad motor pattern habits, that working on how the hip extensors function can be very, very useful for those athletes.”

“So if I am a S&C coach, and I am working in a professional club, and I have sold the coaches, that I need an extra 10 minutes per day, Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday for an activation session, what would you recommend that looks like for a group? Do we continue down the glute activation? Because that potentially, based on your previous comments, could be beneficial ?”

“Now, that’s an unanswerable question in the sense that what you would have to be doing is you would have to understand how your players are moving. You have to be thinking about what you believe their current weaknesses are and then if you could improve the way they move, that would reduce injury or improve performance, what exercises would they be? Now, first of all, it’s going to be different for every individual. So you are going to have to prescribe it individually. But let’s pretend that most of your athletes are running in a certain way. Well, the thing is, is that what I would ask is, whether doing some side shuffle glute band stuff is actually going to then optimize the technique you are trying to improve, whether that’s running, running acceleration, changing directions, swerving, whatever it is.

That is if your rugby player is not getting low enough to engage in a tackle, should you be imitating something like that with walkover lunges, or bear crawls on the ground to improve the mobility through the hip? If you have got an athlete that is struggling to decelerate, you might want to then just give a couple of opportunities to decelerate. A lot of athletes have a problem decelerating, and then changing direction and re-accelerating. And so the idea of actually giving them a specific task might be better. And if you want to really peal it back again to replicating glute activation, you know things like one-legged walk over lunges so that we can practice how the hip is going to extend from that, flexed position where we are relatively weak, you can do those kinds of, I guess, activation exercises to remind the brain of where the pelvis is in space, where the hip is, and to remind the brain to make sure that you are using glutes, hamstrings and everything to actually extended the hip. Every coach is probably aware that if you want to optimize a complex task, it can help to break the task down into smaller chunks, allow an understanding of those chunks and then build it back up. And I would argue that as the S&C Coach, you have got the opportunity to do exactly that. And if it looks like a glute band exercise, because you have decided, whatever, that’s not for me to judge, if it looks like a walkover lunge, or it looks like a sprint running drill, or it looks like whatever, that’s up to you. But breaking down a task, and then building it up is not a bad way to spend 10 minutes of a warm up.”

“The influence of the track coaches has made its way into the team sport world and having the audience that we have got mainly in a team sport environment, should they be looking to the best sprinters in the world and saying “I need to use that as my technical model. I need to move my athletes towards what that looks like” Or should we have an alternative model that is more appropriate for my athletes?”

“So there’s a global understanding of how most humans would relatively optimally run at high speed. There’s a certain configuration of the leg that if we get it about right, we are actually able to store and release elastic energy. These sorts of ideas, I think are good for every team sport athlete, and there’s no doubt that having a basic understanding of running mechanics and doing basic sprint running training is going to be good for athletes. And, I guess in the US a lot of them have done track at high school, and then they go on to the NFL and they can run, their mechanics are actually really generally very good, not comparing to the elite. I guess the thing that differs is that first of all, there are individual differences. Second of all, you can’t spend all your time doing sprint training. It’s a bit like the S&C coach who wishes they could spend all the time of the athletes in the gym. That’s just not going to happen.

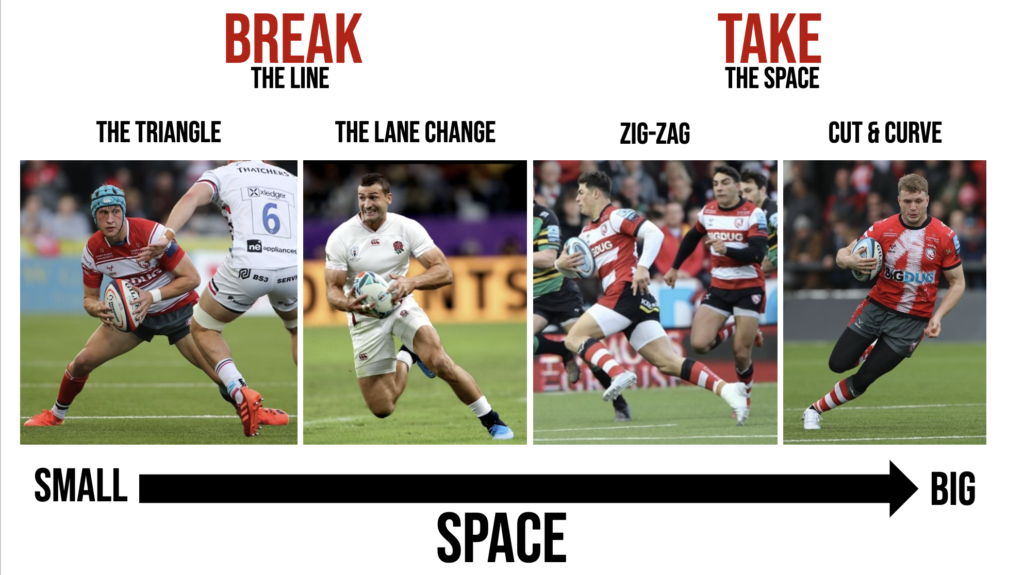

But first of all, there are some nuances. There are some differences in how someone has to run when they are on a field, changing direction and responding to patterns that are in front of them. There’s no doubt that you can only change direction when your foot is on the ground. So having a longer stride may not always be optimum, because you can swerve at long stride, but you can’t change direction effectively at long strides, we may never try to deliberately run our fastest. A lot of running backs say, “I never actually try and run as fast as I can,” because you are so busy scanning and manipulating that you are not necessarily trying to run as fast as you can. Centre of gravity might be slightly lower, because remember, to change direction, you need to land with some knee flexion and push outwards. And if you are high, you literally can’t do that. And there’s an ACL risk there, because you can align with a straight leg. So there is the idea of keeping centre of gravity lower during acceleration and waiting for changes in direction. There are lots of reasons or lots of ways that I would argue that we manipulate the technique to reduce arm length, stride length, lower centre of gravity, and increased stride rates that are useful in the field sport context that we wouldn’t teach a 100-metre runner. So again, maybe the answer to the question is globally, yes, I actually do believe that understanding how to teach someone to run fast is useful. But then understanding then what you are actually trying to achieve on the field or the court and optimizing that motor pattern is really an important consideration. So just getting someone who can run a fast 100 meters doesn’t mean, they are then going to be extremely good at a sport.”

“So you mentioned sprint drills there. And again, it’s something that’s come up multiple times in conversations with guys that are in the trenches every day with team sport athletes trying to get them fast, or sprinters trying to get them fast. Do you see that there could be potentially poor use of sprint drills, lack of understanding of what the actual end goal is for these particular drills?”

“Yeah, and so in my opinion, my current belief system, where I am at the moment is, again, if we think about trying to learn a very, very complicated movement it is very useful to break it down into smaller components and make sure that the brain understands where the body is in space, then start to move it faster, then start to add on more and more components until we learn a complex activity. In sprinting, which is a very complex sport, we might argue that what we call sprint drills are meant to do that. And I personally have had a lot of success in taking chronically injured athletes and not only improving mobility and balance and a few other things, but taking them back to basic sprint running drills. Because what they are then learning is where their body is in 3D space and getting the nervous system to be able to control this hugely complex environment to move in a pattern that is much more optimum for performance and also for reducing the risk of injury.

And so, if we just take something like a knee lift drill, why do a knee lift? Notice I never call it the high knee lift drill. And that comes down to the cue that if someone’s trying to do the highest knee lift, they tend to lean back, the toes are pointed. I mean, what’s the point? There is none… I can’t understand the reason for that kind of drill. And that’s where we see it, we see people doing drills, but not actually understanding what they are trying to achieve with the drill. Some of the common drills, I never use, to be honest, because I am just not sure what I am trying to learn from it. But if you have got a set of drills, where you know exactly what you are trying to get the human to achieve, and then you build them up into a run. And then if you notice that there’s an issue, you might come back and work on another drill, and then go back into the run and see if that motor pattern has helped. That’s where I think those drills are very, very useful. And if you do them for, particularly from a young age, for years, your body knows exactly where you are in space. And that movement pattern becomes really, really important.

And I will just remind you, because obviously there will be people saying, “Yeah, but the only problem during drills is you have to stay very internal. You always think about where you are, when you are on the field, you can’t do that.” I completely agree. And that’s the whole point right, if every warm up, and every off-season, every pre-season…? Yeah, we do it with our youth development squads from young ages, once it becomes naturalized, you don’t think so much anymore. And that’s the other benefit to warm up is if you just optimized it now, your brain doesn’t have to think, it’s the optimum motor pattern you have just practiced, then you can actually focus on the field and the tackling and the ball and the motor, the patterns that you are trying to achieve external to you and your body should follow a more optimal motor pattern. So I am a big fan of an appropriate drills done with specific rationale in the lead up to proper complex running, change in direction skills.”

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Benefit of warm-up – how can I use that as a way to ingrain optimal movement patterns?

- Band “activation” exercises – adding a band just presents more feedback to the central nervous system to know where the body is in space.

- Best use of warm -up – first you would have to understand how your players are moving. You have to be thinking about what you believe their current weaknesses are and then if you could improve the way they move, that would reduce injury or improve performance, what exercises would they be?

- Condition for the task not the muscle – the idea of actually giving them a specific task might be better [than a banded glute exercise.

- Nuances in sprint technique – there are some nuances. There are some differences in how someone has to run when they are on a field, changing direction and responding to patterns that are in front of them. There’s no doubt that you can only change direction when your foots on the ground. So having a longer stride may not always be optimum.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM

=> Follow us on Facebook

=> Follow us on Instagram

=> Follow us on Twitter