7th annual strength and conditioning student conference at Middlesex University

In this week’s Blog I asked Corina Murray to write a summary of the presentations at the 7th Annual Strength & Conditioning Student Conference, Middlesex University. I hope you enjoy!

About me

My name is Corina Murray, I am currently a student studying Sports therapy at the University of Hertfordshire. I have just completed my second year and am now on a placement year to gain experience ready to go back into my third year. I have been working with APA at Gosling since September and am here until the end of June. I am really interested in Strength and conditioning so this placement has been really good for me and given me an insight into tennis.

Strength and conditioning conference – my blog!

On Saturday 5th of march I attended the 7th annual strength and conditioning student conference at Middlesex university. I haven’t been to a big conference like this before so didn’t know what to expect but found it all very interesting and learnt a lot. There were 4 speakers, Ed Baker, James Wild, Mark Russel and Eamonn Flanagan.

Ed Baker: Wheelchair Rugby Athlete

The first speaker was Ed Baker who spoke about Planning, programming and training of elite wheelchair rugby athletes and the road to Rio.

This was probably my favourite talk as I learnt so much that I never knew before.Wheelchair rugby players can roughly produce 1000w peak power at 5.9 m/s. This is due to the high intensity training they have day to day.

To test things such as acceleration, they use court sprints, as well as testing power to weight ratio and technique and flexibility. However, all of this testing requires a lot of skill due to the lack of function in parts of the body.

No hand function – no problem!! Most wheelchair rugby players have had spinals injuries from as far up as C3-4 so don’t have much function of their hands, therefore can’t perform exercises in the same way as other elite athletes. Their programmes have to be adapted to suit their needs but enable them to be the fittest and strongest in their sport. To be able to move their chairs with speed and power but with little hand function they have to produce force and friction by squeezing in their arms to the side of the body. The neck and core will also be strengthened to ensure they have got scapula control strong abdominals to enable them to turn the wheelchair without using their hands. I

t is also important to do a lot of resisted work such as sprints pushing weight, uphill sprints and interval training. To gain upper body strength it is important to do exercises like pull ups and chest press etc. but how?

Velcro straps have been used with many wheelchair athletes to strap their hands to the bar in a grip position. They can then strengthen the arm and upper body muscles effectively.

Ed’s programme for the elite athletes consist of three training blocks each being 2-3 hours 2 times a week. The first block is Aerobic development which is built up of:

-Interval training

-Low to high eccentric load

-Building up to longer intervals of 4 minutes continuous

-Technical practice, and strength training.

The second training block is the anaerobic power block which consists of:

– explosive and repeatable intervals

– lactic/ alactic explosive power

– maintaining skill training

– regeneration of ATP

The final block is the Peaking block which involves lactate capacity intervals.

Overall this talk was extremely informative as I learnt things about training with wheelchair athletes that I probably wouldn’t have thought about before.

James Wild: Sprint Acceleration Techniques

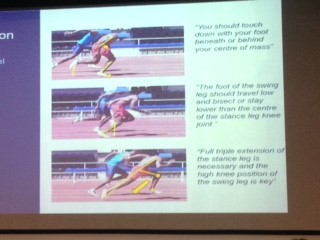

The second talk was by James Wild on sprint acceleration techniques of team sport and sprint athletes and how useful is a technical model?

So are these theories true?

The first question asked was should you touch down with your foot behind or beneath your centre of mass? With every athlete it completely depends on the sport and how quickly they need to accelerate. However, in a sprint your foot will get further in front with every step you take but to start it is more natural for the foot to be behind the centre of mass. 18cm is the common distance from the foot to the centre of mass with the first touchdown but this distance will decrease with every step. Rugby players tend to start with the foot closer as they are in more of an upright position as they need to keep their peripheral vision and generally start the sprint from a rolling start. But, which is best?

It has been found that placing the foot further back gives more of a drive and acceleration whereas placing it under the centre of mass or in front produces more of a breaking mechanism so therefore slows the athlete.

Does musculoskeletal structure affect how athletes sprint?

Bezodis et al (2015) found that the less dorsiflexion of the ankle there is then the more horizontal external power there will be.

Should athletes achieve full triple extension at toe off?

No – there are almost no athletes that get full triple extension when starting. If an athlete triple extends then it is potentially slowing them down as the time to recover from that step and go into the next is a lot longer, it also places a lot of force on the ligaments and tendons surrounding the joint as they would have to work a lot faster. It is rare in team sports to get triple extension anyway as they are not running as fast as sprinters would so therefore not producing enough force. Most athletes in team sports start from a rolling start anyway.

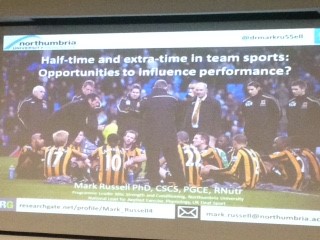

Dr Mark Russel: Half time and extra time in team sports

The third talk was by Dr Mark Russel who spoke about Half-time and extra-time in team sports: opportunity to influence performance?

Half time and extra time are important times for the athlete, half-time gives them a chance to rest, talk about the performance, hydrate and regain some energy. It is also important that their body temperature does not drop too much as this could cause injury in the second half. To ensure their temperature stays roughly the same they should perform another 3-4-minute warm up. However, there can be many barriers to re-warm up such as lack of time and unwillingness from the players and coaches as they will want to recover and have a team talk. If the warm up is not going to be done, then passive heat maintenance should be carried out in the form of extra clothing or foil blankets which will help keep heat in.

Even if the re-warm up is completed, a passive heat maintenance strategy has been found to improve lower body power output and repeated sprint ability in professional rugby union players so would most likely be beneficial to all athletes that get half time.

Before a game begins and also at half time, a 6-10% carbohydrate drink should be consumed so that energy levels do not drop too quickly throughout the game. This will also help players going into extra time as there are generally many reductions in performance in the last 30 of 120 minutes due to fatigue. Keeping warm, hydrated, motivated and keeping energy levels high will all help to improve performance in the second half and extra time.

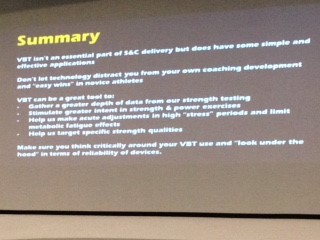

Eamonn Flanagan: Velocity based Strength Training

The final talk was on Recent trends and future directions in velocity based strength training which was taken by Eamonn Flanagan.

I found out that velocity based training is the use of a velocity measuring device to provide feedback during strength training to optimise the strength training process however is not an alternative to strength training. It is not an essential part of S&C delivery but does have some simple and effective applications. It is becoming a lot more popular due to it being more recognised and the technology becoming cheaper and accessible. Before starting any kind of velocity training it is important that the athletes have got plenty of stability and have experienced different types of weight training in the past. Without the knowledge of strength training and their own abilities the athletes should not take part until the coach agrees it is ok.

Technology is important for velocity training however it can become a distraction in the weight room. It is ok to use when completing testing however when you are in the middle of coaching your athletes, leave the technology behind as it can distract the athletes and also yourself which can lead to mistakes.