Isn’t Getting Fitter Simple?

It has often been said that the simplest approaches work the best, and on this basis the simplest way to get fitter is to go out and run around the block a few times, and when that gets easier just run a bit further!! Right? Yes, providing that the name of the game is distance!!

I think we will all recognise when we see someone who is fit (or at least have a pretty good idea) but we also need to explore some of the barriers to being able to develop fitness that will actually transfer where it counts…on the pitch, field, court or track!

Let us not forget that one of the key roles of an S&C coach is to develop a complete athlete capable of performing at the highest level they can free from any physical limitation. In my experience there are S&C coaches who are more big ‘S’ and little ‘c’ meaning they know their way around a weights room and how to get their athlete STRONG but don’t know as much about how to get them fit for the athlete’s sport.

S&C coaches need to understand that while one of their key roles is to get their athletes STRONGER the process of getting someone stronger is a means to an end. It is not an end unto itself! Stamina is important too!

Let me repeat that: It is a means to an end: NOT an end unto itself

It is also progressive journey and if you have already read the APA Philosophy page you will be familiar with the principle of Long-Term Athlete Development.

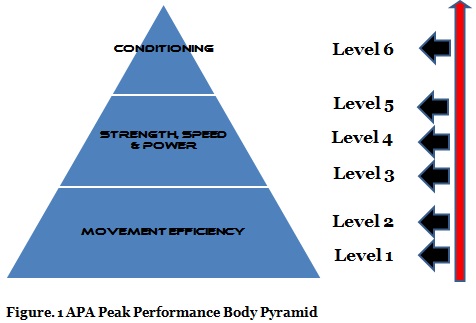

At APA we have created a 6 Stage Training System which is based on developing the athlete progressively. Please see the Figure below for an overview. This relates to not just Stamina but it underpins the principle of how to develop all biomotor abilities

The foundation level is all about developing the movement efficiency of the athlete so that they can move efficiently with the ability to move free from limitation or restriction. This level focuses on ‘Suppleness’ (mobility and stability). We also look at whether the athlete uses well-coordinated effort so that no movement is wasted-known as ‘skill’. I have already talked about the components of Skill in another page- so check it out here for an overview.

Definitions:

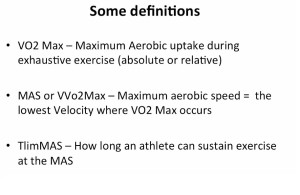

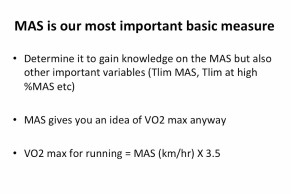

Kudos to Vern Gambetta, Dan Baker and Martin Buchheit for blazing the trail up the stamina path. These guys put me on to the concept of ‘Maximum Aerobic Speed (MAS).’ But before we get into that let’s look at a few definitions so we can understand why this concept is so important. The slides below are taken from Dan Baker’s 2014 Presentation on Aerobic Training Methods for Sports, as part of the Strength & Conditioning Education Inaugural Online Conference.

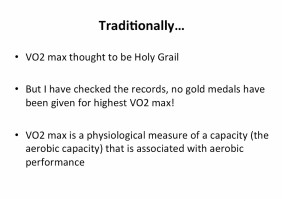

1970-1980s Maximum Aerobic Uptake (VO2 Max)

Initially all the research focused on VO2 Max………it was thought that a large absolute value (in Litres per minute) is vital for a sport like rowing where you are non weight bearing. A large relative value (in ml per kilogram per minute) is vital for weight bearing sports. While a large value will discriminate between elite and sub-elite athletes it won’t explain the difference between winning a medal in the Olympics and finishing last in the heats!

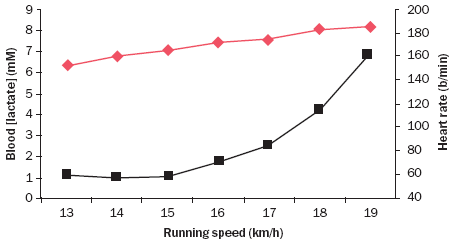

Anaerobic Threshold (AT)

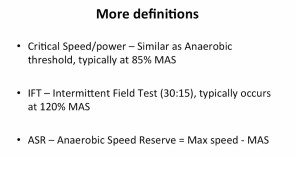

Around the time that study of VO2 Max was at its most popular a growing study of the Anaerobic Threshold (AT) developed, which has been more recently termed the ‘Critical Speed.’ This seemed to point to the fact that the %VO2 Max at which an athlete can sustain is more important.

21st Century Maximum Aerobic Speed (MAS)

As Dan shows here a new term was emerging in the 21st century which relates to a speed factor. Known as Maximum Aerobic Speed (MAS), it’s the lowest velocity where VO2 Max occurs. I like it because speed is a relative measure which can be used to describe intensity of the effort across the complete spectrum from submaximal aerobic work to supra-maximal anaerobic work.

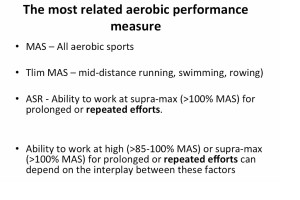

From studying Dan’s presentation it becomes clear how factors related to the MAS take on even more importance for certain sports.

Cyclical Sports of 5-8 minutes

The TlimMAS is the time limit which MAS can be sustained for. This is vital for cyclical sports that take place continuously over durations of 5-8 minutes. After all this is the length of time that we might expect an elite athlete to sustain their MAS for.

If two athletes have the same MAS then the athlete with the greater TlimMAS is going to win over 8 minutes if he can sustain his MAS for 8 minutes and his competitor can only maintain it for 5 minutes.

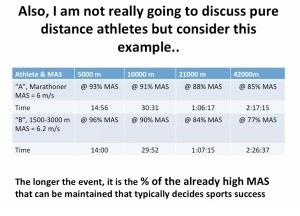

Furthermore, just look at what happens when you study this interplay between MAS and TlimMAS in races of different distances. Over 5km Athlete A gets beat because he runs at a lower percentage of MAS. But over a a 42km marathon he is able to maintain a higher percentage of MAS and comes home first.

Bottom line for these sports is that you need to have a high MAS and be able to sustain it for longer than your competitors.

All training should be based around training at race pace!!

Field and Court based Sports

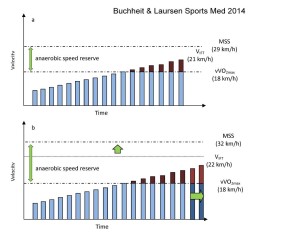

In these sports the action is much more intermittent meaning that plays can last anywhere from seconds to a few minutes. There is a natural built in interval of work and rest to the sport. In these sports it is more advantageous to train at speeds above the MAS, known as ‘supra-maximal’ training. To understand this concept better we need to know what the Anaerobic Speed Reserve (ASR) is.

The Anaerobic Speed Reserve

As described in one of the slides already this is:

Maximum Speed – Maximum Aerobic Speed

For example, 29 km/h – 18 km/h = 11 km/h

To put this into context Usain Bolt might hit 43 km/h at top speed during his 9.58-sec World record 100m sprint, and a typical professional soccer player might run around 36 km/h at top speed with a MAS of 16-17 km/h. So you can think of the Maximum Speed as being at least twice the Maximum Aerobic Speed!

Typically you get two types of athletes: The plough horse, work man like with a decent MAS but not very high Maximum Speed, so they have a small ASR. Then you get the thoroughbreds who have a low MAS but an extremely high Maximum Speed and therefore ASR.

This has all sorts of implications for training prescription which we will get into soon! But first we need to look at how we measure these qualities.

How do you measure Maximum Speed and MAS?

Measuring maximum speed should be fairly easy. Just measure your athlete doing a rolling start over 20m.

Measuring your MAS is also pretty straight forward but there are a few different approaches.

Option 1: Laboratory

At APA I have used two versions of an incremental running test. The first version is for the field sports athletes for whom running is not their actual sport. For men we start them at 6 km/h on a 1% gradient and increase the treadmill speed every minute until exhaustion. Expect scores of more than 16 km/h. For the females we do the same protocol but start at 4 km/h.

For the elite athletes for whom running is their sport (track & field) or just very highly conditioned athletes we do the same test but start at 9 km/h for the men and 6 km/h for the women.

The pros of doing this type of test is that it is very reproducible. The con is that it is on a treadmill!

Option 2: 6 minute time trial

This is a great way to determine the MAS.

Just take your athletes to the track and find out how far they run in 6 minutes. Obviously you can split the track up into 50 metre splits so they can measure to the nearest 50 metre zone. The pro of this is that it is very easy to accomodate large groups. The con is that you will have difficulties in the initial trials getting the athletes to pace themselves correctly. It’s also more difficult to manage as you are reliant on the athlete knowing how many laps they have done unless you have enough coaches to monitor this.

This is why you may opt instead to have a fixed distance that you know the majority of your athletes will complete in around 6 minutes, so this may be between 1000m and 2000m depending on the stage and level of the athlete.

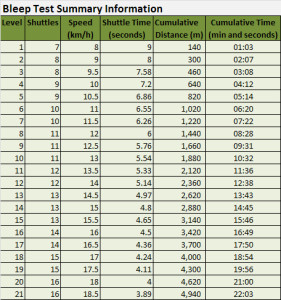

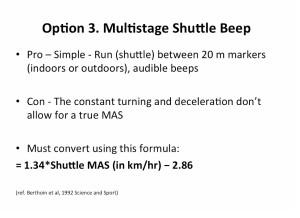

Option 3: Bleep Test

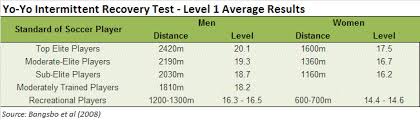

Option 4: Yo yo Intermittent Recovery Test- Level 1

I personally don’t use the Bleep test any more because it takes 15 minutes and 3000m to get to the sort of running speeds that actually pushes good athletes. I want to spend as little volume as possible doing things that will just make the legs heavy and slow. This is why I got rid of this in favour of the Yo yo Intermittent Recovery Test.

The starting speed is faster (10 km/h versus 8 km/h) and it goes up to (19 km/h) meaning it takes a little less time. Typical elite performers will get up to about 17-17.5 km/h. You will reach fatigue in less distance (around 2000-2500m for the sub elite and elite athletes). The most important thing to know is that it is thought this test may take the athlete into their ASR, so they are borrowing a little bit from their Anaerobic metabolism to complete the final stages of the test.

There has been formula published for estimating VO2 max (ml/min/kg) from the Yo-Yo IR1 and IR2 test results (Bangsbo et al. 2008):

Yo-Yo IR1 test:VO2max (mL/min/kg) = IR1 distance (m) × 0.0084 + 36.4

Critics of the Yo yo test

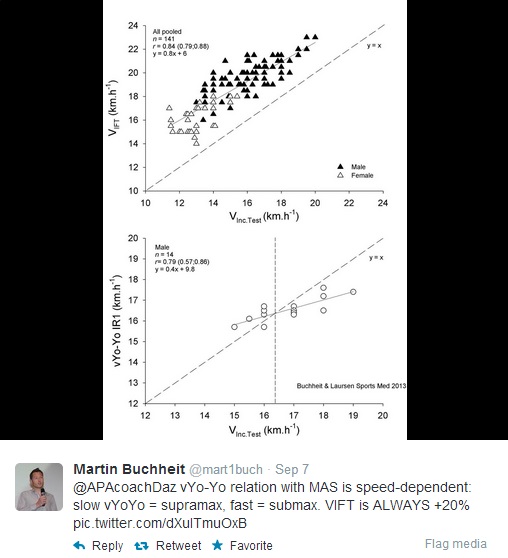

Martin Buchheit won’t mind me saying that he thinks the 30-15 Intermittent Fitness test (IFT) is better than the Yo yo test

According to his research the V-IFT is always 20% above the MAS whereas V-Yo-yo can be above and below the MAS dependant on the individual athlete. On this basis I usually assume that my yo-yo test is a good predictor of MAS.

To cover my bases I usually do the Yo-yo test in squads as it is efficient and do an incremental treadmill test with my individual athletes so I have a couple of measures to compare.

How to you Train using the Maximum Aerobic Speed

Well this could be a pretty long topic in itself. I’m not going to get into all the possible training prescriptions here. I just want to cover off a few key principles.

There are 3 types of speed that your athlete’s body needs to know!

- < 70% MAS for recovery

- Race pace

- > Race pace

The only people that need to consistently do long slow distance running are you guessed it…….Distance runners for whom Race pace might be a two hour run at 85% MAS. This is because their race pace is a sub-maximal running speed. At APA most of our stamina sessions that aren’t designed to promote recovery are at 90% MAS-140% MAS. That’s where the majority of my athletes need to be working.

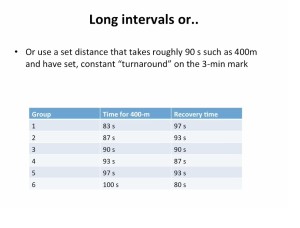

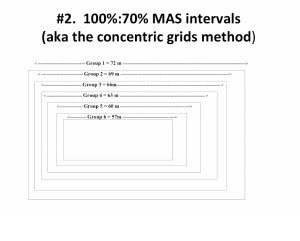

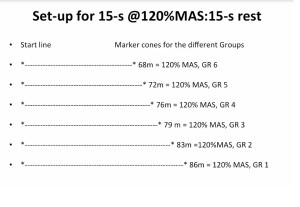

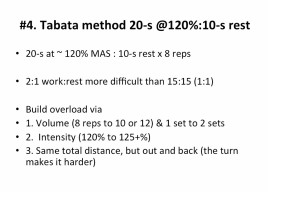

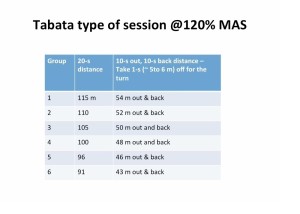

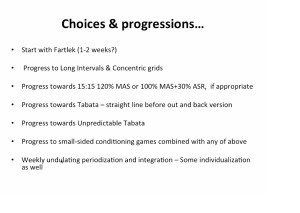

Here is a basic progression from Longer Intervals of 3 minutes to GRIDS (15-s work at 100% MAS: 15-s active rest 70% MAS) to EUROFIT (15-s work at 120% MAS: 15-s passive rest ) to TABATA (20-s work at 120-140% MAS: 10-s passive rest)

We will build up the intensity from 92% MAS to 120% in these first 3 progressions

Then comes the nasty work at 120% plus!!!!!

What next?

From here we would get into our supra-maximal repeated sprints. At APA we emphasise linear repeated track sprints first and then emphasise repeated shuttle runs with changes of direction.

Long-term Athlete Development

Puberty is a ‘Game Changer’ as this is when we can start to crank up the intensity of the training using many of the methods I’ve described above.

Table 1. APA 6 Stages of Development

|

Girls |

Boys |

||

|

Fundamentals |

Level 1 |

6-8 years old |

5-9 years old |

|

Learn to Train |

Level 2 |

8-10 years old |

9-12 years old |

|

Train to Train |

Level 3 |

10-12 years old |

12-14 years old |

|

Train to Train |

Level 4 |

12-14 years old |

14-16 years old |

|

Train to Compete |

Level 5 |

14-16 years old |

16-18 years old |

|

Train to Win |

Level 6 |

17 years old+ |

19 years old+ |

As you can see, an athlete will spend the majority of their formative years (pre-puberty) in Level 1 and Level 2 learning how to coordinate proper movements. As it relates to Strength this means learning how to get the body into the proper positions to perform different types of Strength movements:

APA Stamina development Pathway:

| Stamina Focus- Based on Percentage of Maximum Aerobic Speed (MAS) | |

|

L1 |

Games: (Tag games/relay races/partner activities/skipping contests) |

|

L2 |

Continuous runs and Long Intervals: Train Aerobic system using 20-30 min runs 85% MASand shorter 6-8 minute fun obstacle courses / sports drills |

|

L3 |

Medium and Short Intervals: : Medium: goal 1000 skips in 5 minutes, and footwork combinations for 2-5 minutes. Short: focus on up to 1-minute 100% MAS intervals using runs and SAQ circuits, progressing to 120-140% MAS |

| L4 | Multi-directional Speed: Shuttles: Train Anaerobic System using repeated there and back maximal effort sprinting, known as shuttles. This is the basic form of sport specific conditioning. |

|

L5 |

Multi-directional Speed: All Directions: Train Anaerobic System using repeated maximal effort sprinting in any direction. This is the basic form of sport specific conditioning. |

|

L6 |

Straight Ahead Speed Repeated sprints: Train Anaerobic System using maximal effort sprinting and jumping. This is the highest intensity form of sport specific conditioning |

The Table above highlights how the skill of running is a main focus as younger athletes move out of the ‘Foundation’ stage and start to train the skills. Level 3 to Level 6 is associated with performance enhancement focused on running at speeds around MAS and above. We test and train biomotor abilities associated with gross athleticism such as strength and speed. This tells us about how efficient an athlete is at generating power! It’s important to test the skills under conditions of more stress by progressively challenging the body under ever increasing levels of fatigue.

We will assess the athlete in all areas of the Peak Performance Body Pyramid all of the time but the distribution of time spent training the different qualities will be based on what the assessment shows and the athlete’s stage of development.