APA Philosophy 7- Sets x reps

So now that you have a basic idea of the exercise selection and what order I would work the different components we need to have a look at the typical recommended Training Load for these different exercises. I am going to jump straight in with some guidelines from the ACSM.

Suggested Repetition Ranges

Population Rep Range Healthy participants under age 50-60 8-12 Pubescent children Pre-pubescent children 8-15 Individuals older than age 50-60 or frail persons 10-15 Individuals primarily interested in muscular endurance Cardiac patients with physician’s approval 10-12 Pregnant women without contraindications who have previously participated in weight training 12-15

ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 7th Edition

ACSM’s Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 3rd Edition

Now, with all the coaches at APA I have used the 6-15 repetition range as a guideline for the muscle conditioning or accessory exercises for Level 3 onwards where you are working against some load. This fits pretty well with the ACSM guidelines of 8-15 repetitions. Obviously at Level 1 and 2 where it is all body weight for the most part you can exceed that repetition number and where the ACSM stop at 15 I will often go a bit further and get my youngest athletes doing up to 20 repetitions on certain exercises. These guidelines apply to weights lifted continuously, which we know as ‘weight training.’

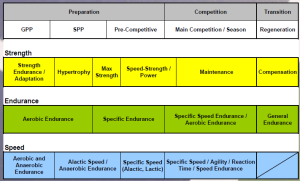

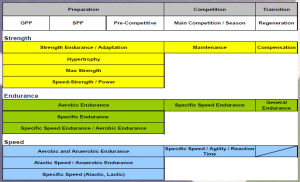

Remember, we will also have our children doing Olympic weightlifting and Power lifting so the recommendations that I give for these type of exercises are a little different. The children may be in a learning phase and we will want to get them doing a lot of repetitions but not necessarily one after the other continuously. So for these types of lifts the reps will always be less even when they are learning because we want them to get used to applying total focus to every repetition. Again, I must thank Jamie Smith for doing a great job of neatly describing the repetition ranges for the various categorisations. I put the terms in parenthesis as they relate to APA terminology so it is clear. In a typical session we will work from Left to Right starting with the Power >> Strength >> Muscle Conditioning >> Energy System development.

|

Methods |

Maximal Effort (Strength) |

Dynamic Effort (Power) |

Sub-maximal Effort (Muscle conditioning) |

Repeated Effort |

Metabolic Effort |

|

Training Load |

1-5 Reps (Depending on training level) 90% + 5-8 Sets *I personally go in with 4-8 reps initially at 80-90% 1RM with Level 4 then progress to 1-5 at Level 5/6 |

1-5 Reps (Depending on training level and Movement) 40-70% 5-10 Sets

|

4-10 Reps (Depending on training level) 80-90% 3-5 Sets *I personally go 6-15 reps Level 3 with 8-12 being typical at 65-80% 1RM moving to 6-10 at 75-85% 1RM |

10 + Reps (Depending on training objective) < 75% 2-4 Sets

|

Rep/ set scheme will vary on the different energy system methods, circuits, complexes, timed sets, density training, medley conditioning, and countdowns

|

|

Training Effect |

Development of maximal strength

|

Development of explosive strength and the ability to produce force in the shortest amount of time

|

Development of muscular hypertrophy

|

Development of strength endurance and restoration

|

Development of general and specific work capacity

|

|

Exercise Classification |

Primary and Secondary Movements

|

Explosive and Primary Movements |

Primary, Secondary, and Assistive Movements

|

Secondary, Assistive, and Auxiliary Movements

|

Secondary, Assistive, Auxiliary, Energy System Movements

|

I can’t really argue with the numbers from Jamie. As discussed above and if you read my previous post on Stages of development you will see I went in at 6-15 repetitions for our Level 3 Anatomical Adaptation / Hypertrophy phase and yes I would typically work around the higher 8-12 repetition range with beginner athletes and I like to move into the lower 6-10 repetition range for intermediate athletes. We call this part of the session our muscle conditioning. This represents the biggest part of a novice athlete’s training (overload) in the gym.

For Strength I would say that I initially like to work around the 4-8 range to bridge the gap between hypertrophy and pure Maximal Strength. This is our Strength part. For our level 4 athletes and above this represents a significant part of the training effect. For our novice athletes they are learning technique.

I like 5 x 5 programmes and 8-6-4 programmes. Once we have got a few cycles in the 4-8 range we can come back to Maximal Strength and hit the big numbers at lower reps, around the 1-5 mark. This is advanced training. Having said all of that any work involving the barbell such as squats, deadlifts, bench press, overhead press and even chin ups I like to focus on doing no more than 8 reps or so in a row even with technique training as I want the athlete to focus on doing each rep with perfect technique. This means that our beginner athletes will still be doing 4-8 repetitions at this section in the session even though the weight is light.

The final point to make is that with the Velocity Dependant lifts such as the Olympic lifts (which is the Power section) I will generally get the athlete to do no more than 3 repetitions in a row and only if it is part of a combination where you are breaking down the lift into sections. Even if it is technique work and we want to do 10 cleans, or 20 snatches every rep needs to be completed with a pause between each one where they release contact with the bar. So the Power section is always done for quality. With advanced athletes you can get them to rep out cleans etc for a conditioning effect both in preparatory and pre-competitive training cycles but then it fits into a different section, with a different purpose!!

Varying Workloads: What does the Research say?

I just wanted to throw a curve ball out there because so far I have only presented my way which is to train concurrently by targetting all the parameters in every session. Below is some research on how you can alter workload from session to session.

Making workload alterations (8RM, 6RM, 4RM) every workout was more effective in eliciting strength gains than doing so every 4 weeks.

Rhea MR, Ball SD, Phillips WT, Burkett LN (2002). A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for strength. J Strength Cond Res. 16(2):250-5.

Hunter et. al. compared variable resistant training (once-weekly training at 80%, 65%, and 50% 1RM) versus training 3 times a week at 80% 1RM in men and women over the age of 60. After 6 months both groups made similar strength and lean body mass gains. However the variable resistant training group reported lower perceived exertion during a carrying task.

Hunter GR, Wetzstein CJ, McLafferty CL Jr, Zuckerman PA, Landers KA, Bamman MM (2001). High-resistance versus variable-resistance training in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 33(10):1759-64.

I am open minded and want to make sure that just because I like to do something a certain way doesn’t mean that I think it is the only way. For me there is no question that Variation is an important training variable to consider. I believe my programmes have in built variation in every session because I work on Power, Maximal Strength and Muscle conditioning in EVERY session. I vary my training load from week to week by manipulating the volume load (sets x reps) on a weekly basis in Strength exercises and vary exercise selection every cycle in the muscle conditioning exercises. I don’t like to have the type of variation in my strength parameters described above because I personally want to hit every part of the Force-Velocity curve every session, but clearly evidence supports it works!! Something for you to ponder in your own programme design!!

Well that about sums up the basics of the Training Load parameters for now. I’ll be back with a post on Training Frequency / Density and a few more golden nuggets from my Coaching Mandate and that will wrap up the big 10 APA Philosophy Posts!!!