If you haven’t read the first blog post then read it HERE. For this final instalment I want to talk about two further points:

- Observing performance

- Giving and receiving feedback

These two points are actually secondary for me when I’m interviewing a prospective coach because I believe that the passion to inspire an athlete by creating a great training environment is what I look for first. The technical knowledge to know what to observe and give feedback on is something I feel I can teach more easily. But if you can do both then even better!

Observing Performance

A big part of your role as a coach is to observe performance. You observe the athlete’s performance and evaluate it. First and foremost you have to set up a great training environment to ensure that the athlete is giving you an account of their best effort. If you have failed in achieving the first task then there is no point observing something where the athlete is not trying.

So observation has to be an integrated approach starting with mental effort (i.e., their mindset to give 100%).

A good checklist to apply is observe performance and provide feedback in the following order: Drill, then Will, then Skill

Drill– are they doing the drill the correct way? So are they using the correct equipment, are they following the instructions?

Will– overall does it look like there is Mental & physical hard and smart (engaged) work taking place?

Skill– are they using the correct techniques to get the outcome?

This process applies for all athletes. But we do need to consider the different needs of different levels of athletes.

Observing Advanced Athletes: the mouse in the room

Have a look at my previous blog where we observed and analysed the Snatch Balance (aka Drop Snatch) below:

Now clearly in this type of setting you need to know your stuff. The athlete is highly motivated and the Drill and Will is being observed properly. You need to have a good level of technical knowledge and you need to know what the fault is that is creating the failed lift when you are observing performance. The slight heel lift of the left foot is the ‘mouse in the room.’ It’s a small fault but it makes a big difference to an elite athlete’s performance. This heel lift is the skill that needs to be addressed.

Observing Novice Athletes: the elephant in the room

Again observation skills are really crucial here as there are some much more obvious dysfunctional motor patterns that can be observed here that require feedback. With novice athletes there may be several things you have observed that you want to give feedback on. In a previous blog I talked about how novices provide inherent variability in their performance (which creates a great learning environment). So the tendency might be to try and correct all the movements by raising their awareness to all of them. But another approach suggests we should keep them focused on the task outcome and limit how much feedback we give them.

So how much feedback should we give?

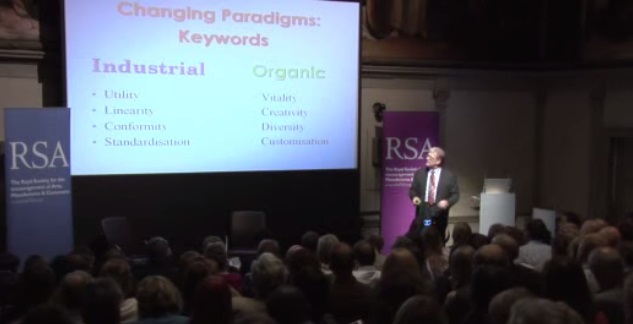

Forgive me for going off on a tangent but I have recently been inspired by the views of a pragmatic educationalist called Sir Ken Robinson. For me I see a lot of parallels with coaching and teaching, and it’s in the way we teach (and give feedback) that we can really make an impact on the athlete we are working with.

This lecture is in the context of education and children but I think it applies to any learning. If you don’t want to watch the whole lecture, the key point he makes is that ”children are learning organisms. Children don’t need to be helped to learn for the most part. They are born with a vast veracious appetite for learning. Children just pick things up. Of course you nudge them, you correct them, you encourage them. Children’s appetite only starts to dissipate them when you educate them and force feed them information. Children learn any way. But the conceit of education is that we can help them learn it better than if they were otherwise left to their own devices.(if we do it the right way)”

He talked about the flipped classroom approach: where you don’t teach them everything. You get them actively involved in teaching themselves and teaching each other.

Ives & Shelley talk about the need to develop a ‘non-awareness’ strategy, which relates to the same idea of letting the child take control of their own learning through discovery learning.

So what is Discovery Learning?

Discovery Learning is about learners solving for themselves how and what movements to make given the SITUATIONAL CONSTRAINTS imposed upon them. We will discover below that the constraints are key aspects we can control to influence the performance of the task. This becomes especially important when we are dealing with more advanced learners whose skilled are more developed.

Working with Beginners

In the case of working with beginners or any situation when we are introducing a new skill to an athlete we could look at giving minimal coaching technical feedback and simply letting the athlete come up with the solution. They will bring their own inherent variability to the party because they are learning to coordinate their body.

Ives and Shelvey (2003) say:

”To illustrate for functional training, we suggest that athletes not be told to perform weight training exercises with specific techniques. The athlete,within the bounds of safety, should be free to explore the exercises and become aware of their own movement effects and perceptual outcomes. Don’t rigorously defining‘proper’ form. With no instruction, the athlete may search endlessly for a proper movement solution.

A word of caution:

Athletes may learn poor movements and adopt bad habits.

The coach or trainer can guide the athlete by providing purposeful intent, ideas about where to focus attention, and clues to key perceptual cues. In this fashion, athletes are able to resolve problems and begin to understand the nature of movement on their own, and determine optimal solutions for themselves.”

In summary we can view the role of the coach as guiding the athlete to optimal performance through giving them a clear instruction on the intent we are looking for, and a few attentional cues BUT letting them solve the movement problem!

Now this may be quite a lot of information to digest. This is specifically focused on skill related feedback. On a more global sense I have found the check list below very useful when considering the relevance of any feedback I want to give.

|

Coaching Skills – Feedback

|

Observations

|

|

Coach to provide BESST feedback

|

| Black and white |

| Simple and clear, success-failure boundary, giving a sense of urgency as it is or it isn’t.

The task and its processes offer ‘No wriggle room’. |

|

| Effort emphasized |

| Effort emphasised e.g. “Well done. You worked hard for that.”

The simple message to be reinforced through feedback is effort grows talent

|

|

| Specific |

| Not ‘Great point!’ but ‘Great determination to get behind the ball.’

|

|

| Solution-focused |

| Praise = ‘Well done, you kept your hand in front which helped you to …”

Encouragement = “Just keep your hand in front.”

|

|

| Theirs! |

| Encourage the learner to give and ask for feedback

|

|

I hoped you found this blog interesting and will challenge your thinking the next time you are about to observe performance in one of your athletes!

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help