3 Topics every S&C coach should have an opinion on!

This blog post is inspired by a really interesting Discussion Forum that recently took place at one of my visits to the National Strength & Conditioning Workshop, at the Lawn Tennis Association. One of the perks of being the Head of S&C at Gosling Tennis Academy is getting the chance to go to these workshops 3 times a year to share best practice and learn from each other.

During one of the ‘break out’ sessions my friend and colleague Dominic King, lead a discussion on a number of key topics that come up as part of our interaction with coaches, medical professionals, and parents. I thought I would select my Top 3 ‘Hot Topics’ and give you my opinion on them.

1. LTAD Model

Check out this link HERE for a full text downloadable journal article: ‘The Long-term Athlete Development model: physiological evidence and application.’

Key points:

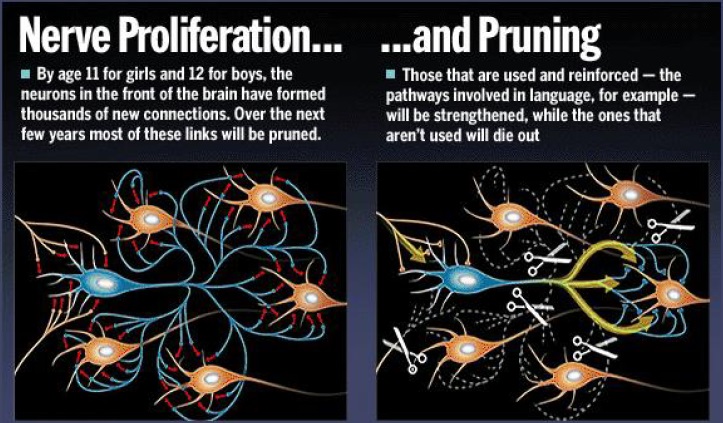

In this article, it highlights that there are key physical developmental processes that occur during childhood and adolescence that might influence short- and long-term athletic performance

- These ”sensitive” developmental periods are known as “windows of opportunity”.

- There is a lack of empirical evidence upon which the model is based, questionable assumptions and erroneous methodologies.

- Fundamentally, this is a generic model rather than an individualized plan for athletes.

- It is crucial that the LTAD model is seen as a “work in progress”

My opinion:

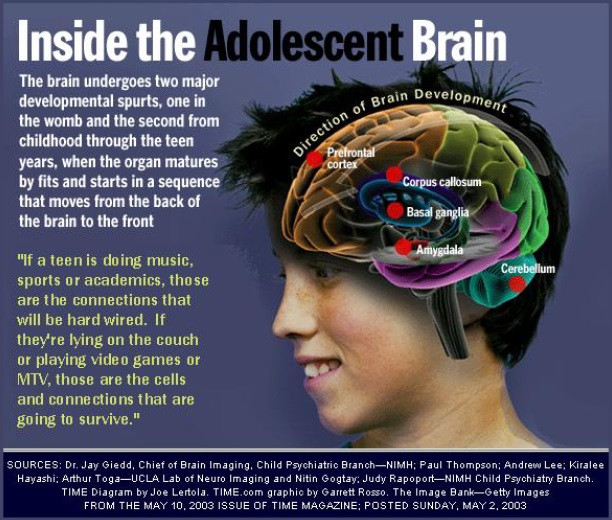

Yes, there are accelerated periods of biological growth; in childhood athletes become more coordinated and in adolescence puberty creates gains in strength and aerobic/anaerobic performance and potential losses in flexibility.

Need Proof?

But I don’t like the term “window” because it suggests that the periods open and close, when in fact they may open and remain so on to and throughout adulthood. Is an athlete suddenly going to reach a speed plateau or have a speed barrier when doing speed training at 16 because the speed window is now closed, I’m not convinced.

One critical biological marker is puberty. I do feel that this is a good indication of when someone may be able to handle more intensive training methods (pre-supposing they have good movement efficiency and an appropriate training history). For the period of training before puberty I still believe in training all the biomotor abilities including strength. I’m more inclined to have training priorities based on what my assessment of the athlete shows, rather than basing it blindly on a windows of opportunity framework. A young athlete could already be lighting fast but lack stamina, but if I just hammer away at speed I will never be addressing their stamina until they are much older.

2. 10’000 hour Rule

The 10,000-hours concept can be traced back to a 1993 paper written by Anders Ericsson, a Professor at the University of Colorado, called The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance.

Check out a great review of the topic HERE

Ericsson has pointed out that 10,000 was an average, and that many of the best musicians in his study had accumulated “substantially fewer” hours of practice. He underlined, also, that the quality of the practice was important.

Malcolm Gladwell places himself roughly in the middle of a sliding scale with Ericsson at one end, placing little emphasis on the role of natural talent, and at the other end a writer such as David Epstein, author of the The Sports Gene. Epstein is “a bit more of a talent person than me” Gladwell suggests.

My opinion:

I’m inclined to sit somewhere close to Gladwell. I do believe that natural talent plays a big role. I like the idea of ‘Nuturing Nature.’ I believe everyone has the capacity to improve and achieve their peak performance potential but I believe only those with an amount of natural talent will be able to perform at the elite level. For some sports this is clear cut; a wannabe sprinter needs natural speed and a wannabe marathon runner needs natural endurance. Other sports need high levels of skill requiring lots of practice- how much is the more difficult question to answer.

One of the difficulties with assessing whether expert-level performance can be obtained just through practice is that most studies are done after the subjects have reached that level.

It would be better to follow the progress of someone with no innate talent in a particular discipline who chooses to complete 10,000 hours of deliberate practice in it.

At Gosling Tennis Academy the parents are advised that the Tennis journey is a 20,000 hour one. You need to aim to get to the first 10,000 hours in around 10 years so someone who starts at 5 years might reach expert level in the skills of Tennis by around 14 yrs old. Then expect to spend another 10, 000 hours transitioning from junior ranks to professional level.

I personally feel that this guide needs a massive ‘caveat.’ That there is no guarantee that you will become an expert (read that as ‘professional’) if you commit to doing 20,000 hours.

I also feel you need to state that it is an individual journey and I believe that those who have more talent will need less hours of practice.

I prefer to say, you need ENOUGH practice to develop the skills of the sport to a competent level- so you have skills that will stand up to the demands of the game under time, space and fatigue pressure. Those children who have less talent for the sport of Tennis may need to spend more of their time practising Tennis. Those children who pick it up sooner can spend more of their time practising other sports.

I’m not prepared to say that everyone will need 10,000 hours to become an expert, and I’m not prepared to say that even if you do 10,000 hours you will become an expert, assuming for the sport of Tennis, for example, that expert means becoming a Pro.

3. Sport Specialisation

Getting straight to the point I believe that all young athletes (pre-puberty) should be doing other sports, in addition to their favourite one. My big 3 are:

[column width=”32%” padding=”2%”]

Swimming

[/column]

[column width=”32%” padding=”0″]

Gymnastics

[/column]

[column width=”32%” padding=”2%”]

Athletics

[/column][end_columns]

I also think that every child should ideally have exposure to a team sport environment, such as playing for a football, rugby, cricket, netball team etc. This doesn’t have to be part of a sports club it can just be representing the school team.

Ideally 2-5 hours of ‘other sports’ in addition to their main sport.

Typically I find Tennis players are committing to playing Tennis any where from 3 hours at 5 years up to around 15 hours at 12 years. But you do need to find time to get the other sports in. At some point down the track, a young emerging athlete may need to specialise and the hours of other sports will be cut to just 1 or 2 so they need to be in sooner rather than later.

Early specialisation vs. Late specialisation

Some sports require more concentrated practise at an earlier age to develop the necessary skills. These are high skill dependant sports like gymnastics and diving. From my experience I would also include Tennis in there too. For example, we are seeing a growing number of younger players (pre-puberty) joining the Tennis Academy full-time, which can involve up to 20 hours of Activity per week (including Tennis and Strength & Conditioning/Other sports).

Is 20 hours a week too much for a young athlete?

Think ‘optimum’ not ‘maximum.’

If an athlete wants to develop the necessary skills in the sport of Tennis then this will require a certain amount of practice, more than the couple of times a week squad practice that you might normally commit to in a sport like Football. But how much more is up for debate.

There are a couple of reasons for this. Firstly, as said above, the skills are more complex. Secondly, the amount of ‘free play’ opportunities in sports like Tennis is less than in sports like football.

But……I believe that not all athletes will require the same amount of hours of Tennis to achieve the same level of skill. I’m not afraid to say that I believe that the more ‘talented’ players will pick things up quicker.

These young athletes have a long career ahead of them. If I can work on an ‘optimum’ programme for them (that looks at the least amount of Tennis I can get them to achieve the desired skill level) I will do that over giving them the maximum amount available. More is not always better.