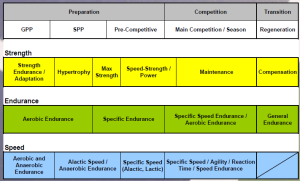

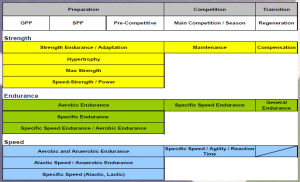

APA Philosophy 6- Stage of Development

So the previous Post, APA Philosophy 5 on Exercise Selection started to build up a framework for an hour in the Gym with a young athlete, but it didn’t go into any detail on how this session might be manipulated to suit the stage of development of the athlete, their goals and the phase of the programme, as well as how that hour in the gym might change if it is the ONLY hour they get with me per week versus it being one of several sessions in the week! Remember, the posts so far have focused on Gym time but we also need to talk about SKILL and SPEED development so we will get to that shortly. Firstly, in this post I want to rap up Strength Exercise Parameters!!

So Below I have included a couple of important Tables which identify 6 Stages of Development that I see in a young athlete’s career. Now before you shoot me down let me say that the ages are just guidelines, and each child may progress through the levels at different rates.

| Girls | Boys | ||

| Fundamentals | Level 1 | 6-8 years old | 5-9 years old |

| Learn to Train | Level 2 | 8-10 years old | 9-12 years old |

| Train to Train | Level 3 | 10-12 years old | 12-14 years old |

| Train to Train | Level 4 | 12-14 years old | 14-16 years old |

| Train to Compete | Level 5 | 14-16 years old | 16-18 years old |

| Train to Win | Level 6 | 17 years old+ | 19 years old+ |

The key points I want to make are that when a child comes into the programme the first thing we can start to do is get an indication of where they might be on their athletic journey based on their physical maturity and training history. Are they pre- during or post-puberty? Have they ever trained in S&C before and what skills have they acquired? Level 3 is Puberty. Everything before Level 3 is pre-puberty; everything after Level 3 is post-puberty.

I am going to describe the progressions through the levels assuming that the athlete has come into our programme as a 5 year old and has stayed with us until their leave High School at 18 years old. Of course this is the ideal scenario but very often we ‘inherit’ athletes along the way and have to try and figure out what gaps need to be plugged!!!

Please refer to my previous post on Exercise Selection where I described my sessions as having a Power, Strength, Muscle Conditioning, and Energy System component. These will always be present but the focus will be different for different ages of children and at different times in the year. Keep going back to that word, ‘Focus.’ Just because we focus on something doesn’t mean other things aren’t being done!!

| Strength Focus | ||||

| Level 1 | Bodyweight Play (Animals/pair work/gymnastics) | |||

| Level 2 | Teach Anatomical Adaptation> SOFT RESISTANCE (0.7BM 10RM) 10-20 r 40-60%1RM | |||

| Level 3 | Train Hypertrophy 6-15 r (1.0 BM 5RM) 60-80% 1RM | |||

| Level 4 | Train Strength 3-8 r (1.5BM 5RM) 75-85% 1RM | |||

| Level 5 | Train Maximal Strength/Power 1-5r (1.75 BM 3RM) 85% 1RM | |||

| Level 6 | Train Maximal Strength/Power 1-5r (>2.0 BM 1RM) 85% 1RM | |||

Level 1: Fundamentals

At 5 years old the child is at Ground Level, Level 1. Istvan Balyi describes this as the ‘Fundamentals’ stage. Now there is a growing trend to move away from strict LTAD principles and LTAD ‘Windows of Opportunity.’ I will give my own opinions on this in another Blog but for now I just want to say that I like the categorisations as they relate to changes in physical maturity. It is important at the very least to reflect as a coach how you will modify (if at all) your programmes as the child matures.

A 5 year old will FOCUS on HAVING FUN and do his/her strength training implicitly using fun imitation games such as pretending to be an animal that squats, and crawls and lunges around!! They also get to do fun partner games and do some basic gymnastic skills. This doesn’t mean we don’t start teaching the children how to use broomsticks (which is the next level)- it’s just not the focus! I guess thought that there isn’t a strict plan of exercises that the children follow for a number of weeks but yes I will put my frog jumps and hop scotch in first to tick the Power element. Then I will do my gorilla walks and crawls for my strength development and there won’t be much direct muscle conditioning in the traditional sense but a good old fashioned Tug O War can tick that box if you want to be anal about it!!!

Level 2: Learning to Train

So when Level 2 comes around the child can be identified as someone who is now ready to receive specific instruction on the technical cues of weight training and we can start running through the basic squat variations as well as introducing the Olympic Weightlifting exercises using a broomstick to take the place of a barbell. Because we start just using broomsticks then I have no problem starting a child earlier if they are ready to receive my instruction and are aware enough to act on the feedback.

Once they have demonstrated good competency on the basic movement patterns then they can start to work against a little more load. I want to get this ‘soft resistance’ phase in early to start preparing the tendons and ligaments so that when puberty does come knocking the body is all primed ready to handle a bit more load. Here we are using light body bars, Swiss balls, medicine balls and most importantly body weight resistance. I can develop a press up and chin all day long and you should look to too!!

We would typically progress beyond the ‘soft resistance’, working up to barbells in training using about 50% of their body mass for repetitions of up to about 15, with a target in testing of 10RM of 70% of body mass.

Level 3: Training to Train

This Training to Train phase lasts for a significant chunk of the young athlete’s development.

Think of this as focusing on the muscle conditioning element while all the time we are developing the techniques of the Power lifts and Olympic Lifts ready for down the line when they become the focus.

Here we go into a more traditional Anatomical Adaptation phase, which is associated with Hypertrophy training. I like to stay here for as long as possible for the reasons already mentioned (get the ligaments ready to handle the force of the muscles). I will start in the higher repetition end of the range, typically your classic Hypertrophy range of 8-12 repetitions at around 65-75% 1RM. Then later on I will progress to the lower end of the range typically 6-10 repetitions at 70-80% 1RM.

These loads would probably be around 70%-80% of their body mass for 6-10 reps, with a target in testing of 5RM of around 100% of body mass. In preparation for Level 4 we may introduce maximal strength training sets and reps schemes, using 5×5 starting with about 80% of their body mass but still using slightly reduced rest periods because the load is still not truly challenging.

Think of this stage as a really hard core version of muscle conditioning but this time using loads up to around 100% of our body mass.

Level 4-6: Puberty and Post Puberty

When a child reaches Puberty (we determine this as onset of the menstrual cycle in girls and Peak Height Velocity in boys) we typically stay in the hypertrophy range for about 6-9 months before thinking about going onto our first Maximal Strength phase. Basically here we just increasingly focus more and more on maximal strength and power. In Level 4 once PHV has passed I like to work in the range of 4-8 reps around 75-85% 1RM using 5 x 5 programmes as a basic introduce with variations around this. This would be following a few initial phases early in the year of muscle conditioning after which we will then really chase some load in this rep range.

Later in the athlete’s development the next time we come back to chasing some load we crank it up again and build up to heavy weights in the 1-5 rep range. It’s around Level 5 and 6 that the Olympic Lifts have developed nicely and on the later stages of our training blocks we will back off the volume of the Strength exercises and really push some big numbers on the Olympic Lifts or whatever power exercise the athlete is competent at!!!! It’s also here where we are at loads greater than 85% 1RM that it is well worth splitting your workouts up into Lower body and Upper body sessions and maybe doing your power work and Strength work on different days.

Well that about raps up the introduction to Stages of Development. We will have a closer look at sets x reps prescription in the next post!