Coping with Injuries

Thanks once again to APA S&C Fabrizio Gargiulo for contributing another great Blog. Fab will be running weekly blogs on the website for the foreseeable future so if you have a topic you would like Fab to write about then please drop us an email at info@athleticperformanceacademy.co.uk

Injuries are common place within sports at all levels and across all age groups. Notably the more mobile joints such as ankles, knees and shoulders are more susceptible to damage as well as the highly used large muscles such as the quadriceps and hamstrings and smaller stabilising muscles such as the rotator cuffs and peroneals. In this blog I will discuss the impact injuries have in terms of training management and the psychology behind managing said injury. I will draw from personal experience on both fronts – being the injured player and coaching an injured player and hope to be able to demonstrate some of the strategies used to success in the past. [BREAK]

Mechanism of injury

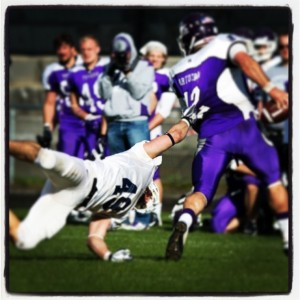

The ‘how’ someone became injured will play a large role in the rehabilitation and the psychological repair of the player. Mechanisms range from over-training, poor mechanics and single traumatic events such as contact injuries. Whilst every injury is individual there is a common series of actions required to getting the player back to full health and fitness and to return to competing. Initial RICE protocols and diagnosis of the injury will prevent further damage. Once a diagnosis is established a path of rehabilitative exercise and management possibly including; manipulation, massage, exercise and alteration of technique can be conducted. These phases can last for varying amount of time, with cases of days, weeks, months and even years before returning to action. Often the initial reaction of an athlete to an injury is met with a wide range of emotions which may include denial, anger, sadness and even depression. An injury often seems unfair to anyone who has been physically active and otherwise healthy. Developing coping strategies are vital to the quick return to the sporting field and for any future issues. Having been on the receiving end of an injury nearly every year that I have competed, I have experienced most of the aforementioned emotions and learnt how to ‘handle’ being injured more successfully, I try to pass these experiences onto my athletes and clients. [BREAK]

Coping during the rehabilitation time

The varying amount of time needed to recover from an injury also has a significant impact on the psychological state of repair. There are several methods of adjusting to cope with injuries; however acceptance is the first key issue – occasionally athletes will refuse to accept they have an injury and continue to play through, often this can be as a result of denial or stress or the importance of the competition. If they are truly injured and continuing will cause further detriment to their physical state they should be removed from competition. Once the athlete has accepted their changed state of readiness they can begin the healing process. This is not to accept blame for the injury but to understand what they are capable of currently and what they need to do in order to return to full fitness and competition. [BREAK]

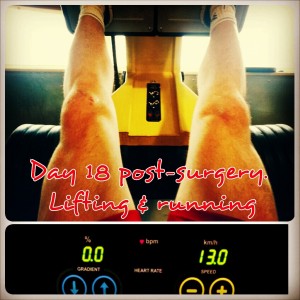

Learning about the injury; how it occurred, what the diagnosis is, what treatment can be done and how long it can take to recover from will all help the athlete to gain an understanding of the injury. In the case of any surgical procedures – something that I have encountered – it is reassuring to know what the surgeon is going to do and how the procedure will work etc. The first time I underwent surgery I was only 21, it was my first major injury and I was very apprehensive going into theatre. The surgery went well, the rehab and recovery the same and I was able to play at the highest level again for 5 more years before I suffered the same injury. This time when I went in for surgery I was far more relaxed and just looking forward to getting it over with and returning to training and playing once again. Having been through the process of having the same injury happen twice and conducting plenty of my own research into how to rehabilitate it and return to competition as quickly as possible, I was confident in my return on both occasions. [BREAK]

Staying involved – I found that this is possibly one of the biggest factors in helping to overcome the injury psychologically, especially in team sports where you are used to having the support network of your team mates around you. In so called individual sports such as tennis, badminton, swimming, equestrian and athletics, the athlete still has a support network of fellow competitors, coaches, medical staff, physiotherapists, massage therapists and possibly agents or performance managers. At APA we have this support team surrounding all of our players and this helps both the player; to have people to stay in touch with on a daily basis and the coach; to draw expertise from different areas. Staying around the training centre also helps the athlete to maintain their ‘athlete identity’. Many athletes, especially if professional from an early age will not have done anything other than play their sport, therefore having a serious injury and having to spend time away from the sport would be a serious shock and can be difficult to handle mentally. Useful ways to keep players involved can be through coaching – supporting the coaches, especially with younger groups of players maintains a sense of the journey they have taken to get to where they are now. Keeping the player in some form of training if possible – a leg injury shouldn’t restrict them from upper body training in the gym or vice versa. Maintaining fitness is also important for a quicker and smoother transition to playing again. [BREAK]

Being professional in everything you do will speed up the recovery process. This ranges from being proactive and precise with your rehabilitation, to managing your mood and behaviour away from training, getting the correct nutritional support into your body and focusing all your energies towards returning to full health and competition. All of these actions require considerable effort and this is why having a team of support around you is a massive help. Regular support from medical staff to reassure the athlete of progress being made and with modern social media, support from people in similar situations can be found from all over. [BREAK]

Returning to competition

Psychologically this is potentially the hardest part of recovering from an injury, especially if you were injured on the field of play. The fear of repeating the injury, having trust in the joint or muscle or not being able to return to the level of which you were previously playing can weigh heavily on the mind. The main supporting factor in regaining trust in yourself is time and making small steps of progress rather than rushing back. However at some point you do need to be in deep enough water to swim. Having people who have experienced similar situations and overcome injuries successfully can be a useful resource to draw from.

Ultimately athletes love to compete and will find solace in being able to return to playing. Patience, support, gradual progress and staying strong mentally are all part of the recipe for success to return to full health and competition.