The Connected Body- Why you need to use Compound Exercises

Please enjoy our latest Blog contribution from APA coach Fabrizio Gargiulo

The human body is vastly complex, comprised of several ‘systems’. Some are commonly known, others less so. Today we take a look at one of these systems known as the Myofascial system. Most people understand the make up of the body as a series of muscles, tendons and ligaments attached to the skeleton, all surrounded by skin and protecting the vital internal organs. In this blog I aim to challenge the belief that muscles are individual and can operate in isolation and to explain why we (at APA) train our athletes predominantly in compound exercises.

The term Myofascial refers to the unit comprised of muscle and connective tissue. Myofascial meridians join the bones, muscles, tendons, ligaments, and connective tissue throughout the body in a web-like chain covering the whole body from the ground up to the head. The connective tissue is what connects a chain of muscles together. The muscles could and should be viewed, not as lots of individual muscles attached to bones, but as a single muscle running from head to toe that attaches at many points in order to allow movement. Indeed muscle is not even attached to bone directly but through the connective tissue – fascia. All too easily, however, we are seduced into the convenient mechanical picture that a muscle ‘begins’ or originates here and ‘ends’ or inserts there, and therefore its function is to approximate these two points. This is certainly how it is taught throughout academia, perhaps for simplicity, however a deeper understanding of the connective tissue enables the S&C coach to better plan and articulate training programmes.

The fascia acts as a ‘double-bag’ surrounding the bones, cartilage, and synovial fluid in the inner bag, the periosteum and ligaments forming the inner bag. The muscle fibres being in the outer bag, with the outer bag itself being formed of structures called fascia, intermuscular septa, and myofascia. In total all the bodies structures are connected via fascia, this can from time to time cause problems when one area is placed under stress or trauma, there is likely a chain reaction to another connected part of the body. However it can also work in the advantage of the body with the ‘transfer of tension’ enabling some outstanding feats of strength and athleticism.

The principle researcher in the area of Myofascial meridians for many years has been Thomas Myers. Myers’ talks about the influence of injury on the fascial system with an analogy – if a tree falls on the corner of a building, the corner collapses but the building can remain intact. Much treatment therapy of the body operates with this view of the body – fix the broken part. If one looks at the body as a tensegrity model, however, the entire structure will give when a stress is applied in one corner. “Load it too much and the structure will ultimately break”. Ultimately the strain placed on a structure is distributed throughout that structure and the tensegrity of the structure may have a weak point, which I likely to be the place of collapse or in the human body, point of pain.

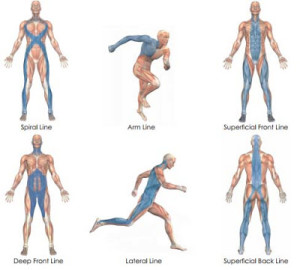

Within the human body there have been several ‘lines’ of fascia identified (sometimes known as sling systems) as shown in the diagram.

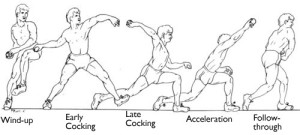

Athletic movements are dynamic by nature and utilise many if not all of these lines when performing sporting actions such as running, throwing, jumping, kicking a ball or swimming. It is important therefore that we as strength and conditioning coaches consider the implications of the training we administer to our athletes – ultimately the goal of which is to improve performance and reduce injury risk.

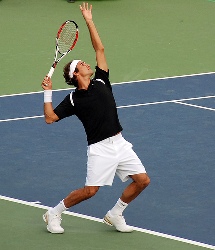

Compound movement training is nothing new, but it is something we advocate highly at APA. Our athletes from a young age are taught strength exercises such as how to squat, lunge, push and pull. With sports such as tennis being multi-directional and explosive, we also focus on teaching landing mechanics, jumping mechanics, change of direction mechanics and Olympic lifting techniques. . Compound exercises are an excellent way of getting the body to utilise many of the lines or sling systems of fascia in the body to stabilise movement, produce power and decelerate the mass of the body.

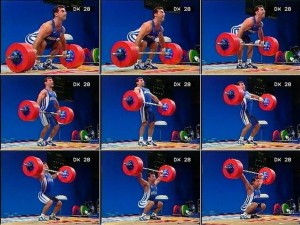

As our athletes develop, the early teaching of compound movements such as squats or Olympic lifts will gradually become loaded exercises. Thus enabling us to strengthen the entire chain of the body; myofibrils, connective fascia and the nervous system that feeds them in order to improve athletic performance. Once an athlete has fully developed, the intensity of the training they complete will be the increasing factor, designed to replicate the stress placed on them during competitive situations.

Specificity vs. Athletic training?

There has long been a discussion about training athletes in the specific movements for their sport. The methodology used at APA is to establish a fundamental athletic base from which sport specific training can be added onto. Our predominant athletic population is tennis players, however many of our young players (5-12yrs) will play various other sports alongside tennis, until they choose to focus on one sport. We encourage young players to participate in many sports whilst they are still developing the cognitive and proprioceptive skills needed. However as APA operates in a tennis environment, we train and improve the movements specific to tennis alongside gross motor skills and compound athletic exercises. One of the primary reasons for compound exercises being used is the range or extent of muscles used as part of the exercise and the cross-over or translation to movements within sport.

Examples of which can be found in the Olympic lifts – primarily challenging the superficial front and back lines – which focus on taking the body from a ‘triple flexed’ position to a ‘triple extended’ position under load. A not too distant example of a sporting move is the serve in tennis, although the added rotation and implements of the racquet and ball make it a more complex skill to complete, the muscular actions are very similar.

Running and squatting also utilise similar musculature and fascial lines…

The superficial front and back lines are predominantly used for both running and squatting.

Throwing and kicking a ball also challenge connective fascial systems and so benefit from training the lines and muscles used in each action, such as squatting, lunging, pushing, pulling, rotating and overhead pressing. The lateral and spiral lines are both involved in actions requiring a degree of rotation.

As you can see in all the photos above the body is being placed under severe mechanical stress and it is the fascia and connective tissue that is holding everything together. Without compound training, the myofibrils of the muscles would be the primary target of strength training as in isolation exercises such as leg extension or bicep curls. By training compound movements we are improving our athletes’ whole body and everything that goes into physically performing an explosive task.

If you are interested in using APA to help you improve your athletic performance please get in touch.

Fabrizio Gargiulo