Why the key to getting faster is to step back first

When you go to a workshop, I bet you have been told that if you want to be fast you need to make sure you don’t step back first. I read this on an American Baseball website recently:

”Standing up on the first step before accelerating is a common mistake that players make when breaking from a base and moving to a batter ball. Another mistake is taking a false or drop step.”

What everyone probably didn’t expect to hear at this latest APA workshop was that this advice and other comments like it are quite frankly totally wrong.

This blog is a summary of the recent APA Speed, Agility & Quickness Training for Sports Workshop, May 24th 2014 covering a lot of different hot topics and dispelling some myths along the way. Buckle up!!

So what did we cover?

We started in the classroom and covered some training principles first

The APA 3 S System (copyright)

Then we went through some videos to better understand what good movement looks like.

Before we get to the videos just a few points. The key to getting faster is:

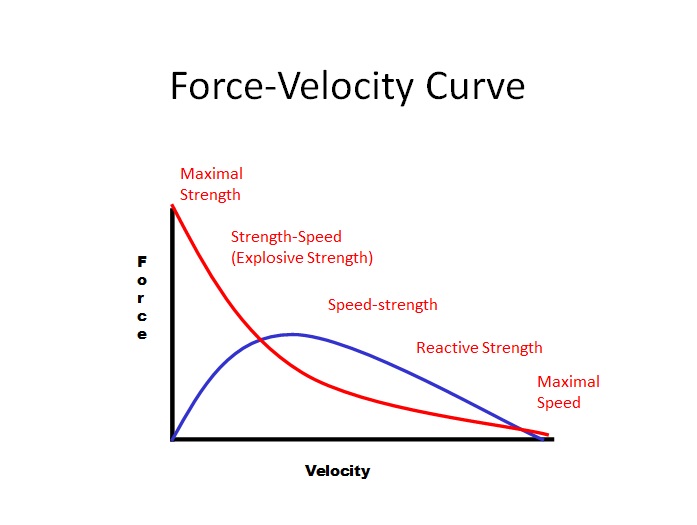

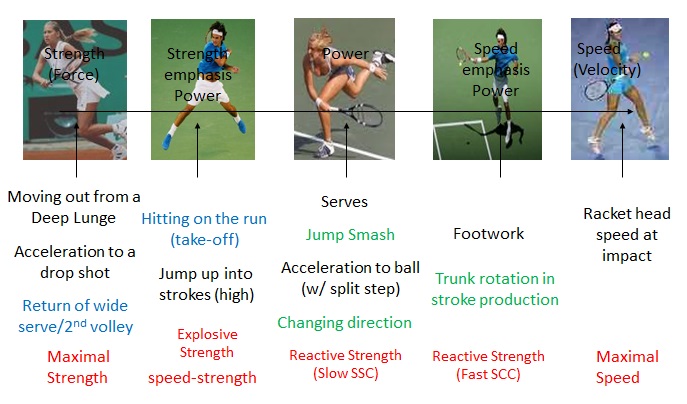

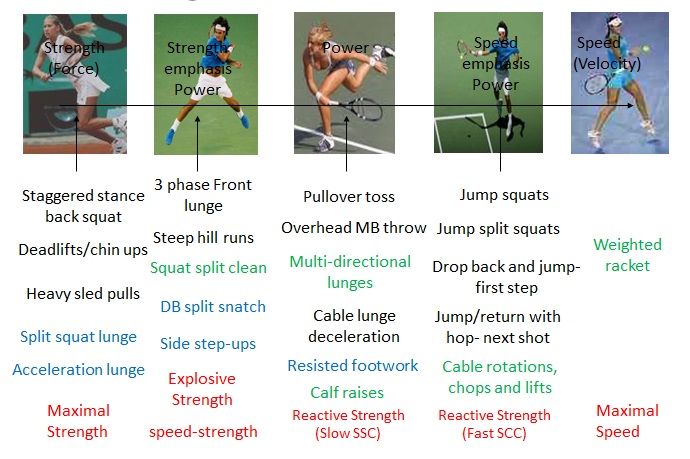

1. The amount of force that an athlete puts into the ground (relative to body weight)

2. The direction of that force

The amount of force that an athlete puts into the ground is improved through strength and power training. In biomechanics they call this ‘kinetics.’ These are trainable qualities. The direction of that force is where the “skill of speed” comes into play. This can be improved through proper positioning and practice and these are coachable qualities . This is known as ‘kinematics,’ and it is here that the workshop was targeted. What does proper positioning look like, and how can we coach that?

Straight ahead Speed

Acceleration:

We looked at proper start position and acceleration mechanics for a 20m sprint. We discussed the differences between a 3 point start and a block start.

Key points:

The stance and start sets the athlete’s force angles for the entire 20m and thus, improving these things will have the greatest improvement on overall 20m time. The key emphasis is to get the athlete to focus on driving (not stepping) out and pushing the ground back with as much force as possible.

We then looked at an example of how this acceleration position might be applied in the sport of Tennis, since the majority of attendees were Tennis coaches.

Top Speed:

We looked at proper foot position for the Top speed phase of a 40m sprint.

Key points:

According to Carl Lewis’s coach (in a pod cast Interview with Canadian Athletics Coaching Centre) the heel DOES come down at foot strike when running at top speed. But I know Dan Pfaff has said that it doesn’t. My opinion is that the foot makes initial contact with the ball of the feet. What we certainly don’t want to see is athletes making initial contact with the heel!!!

What do you think? Leave me your comments below.

First Step Speed

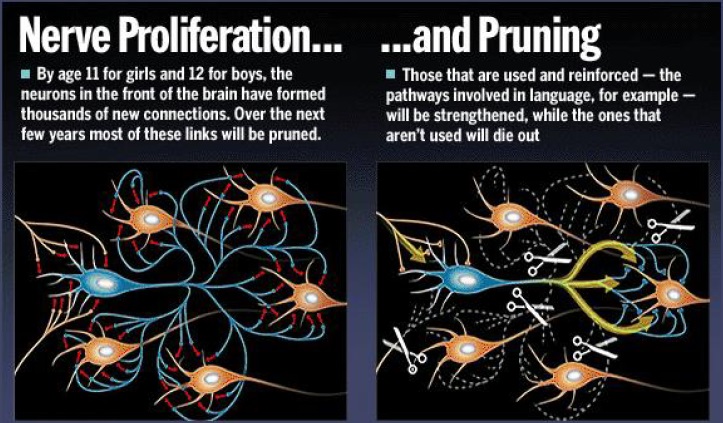

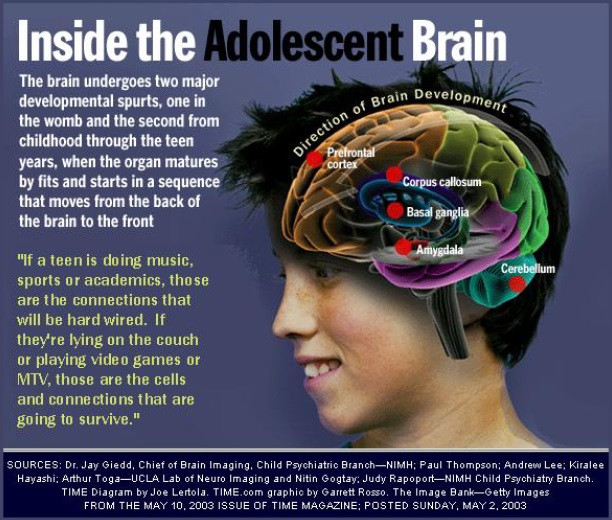

We looked at a 5m start which focuses on the first two explosive steps. Unlike Straight ahead speed used during the 100m sprint, we will typically express first step speed in multiple directions and in response to a random signal to move quickly.

Key points:

I need to give credit to Lee Taft and the IYCA for introducing me to what they call the ‘Plyo Step.’ In Tennis we call it a ‘Dig Step.’ Other coaches call this a ‘False Step.’ Like me, Lee Taft was never satisfied with the irrational explanation that it is a mistake to do this.

He says: ‘I think you will find the logic and the scientific basis of biomechanics and physics will offer enough backing to see the purpose for allowing the Plyo Step to be the way the athlete moves during a reactive setting and from a non-track stance.’

Innovation and creativity is to be congratulated. I always say, ”be an innovator not an impersonator.” Coaches have looked at the plyo step (which is a natural stretch reflex) with this desire to improve sports performance and said, well, this is surely a wasted step, and it must take longer to move forward. But I think they are wrong!

Lee Taft explains:

”The fact that coaches call it a step back just isn’t true. If it were a step back, then the hips would have to travel back as well. This clearly doesn’t happen. Look at the picture of the Plyo Step and notice the position of the hips just prior to the Plyo Step and when the Plyo Step occurs. It can be clearly seen that the center of mass only moves forward. The fallacy the movement brings the athlete backward first just isn’t true. Next, the old timers use to say, “It takes longer to get moving forward”. Wrong again. The reason I named this movement a Plyo Step is because of the stretch shortening action that occurs when the foot aggressively contacts the ground. There is a quick response (action reaction) that occurs from the ground which helps to move the athlete forward much quicker.”

It must be stated that the best position to be able to respond in all directions is the basic athletic stance, with a slight adjustment. The key words here are’ slight adjustment.’ We use the plyo step to reorganise our body position so it is set up to produce force in the correct direction.

Who says, the first step is always going to go forward any way?

Detractors of the plyo step would say you need to step out of the athletic stance by pivoting forward from the ankle. That theory only works if you know the intended direction is going to be forward and you can already lean over the front foot to get into the optimal position to explode forward. Yes, this is correct when talking about a rugby forward or a lineman in American football whose sole job is to move forward and make a tackle. It is also fair to say that this is fairly common in Tennis too when the player knows where the ball is going. But for other sports it has to come from a more neutral athletic stance!

First Step Lateral

In Tennis 80% of all movement is lateral so lateral first step speed is particularly important. Ben Linder, Head Physical Trainer for the Swiss Tennis Federation, calls this ‘1-2 step movement’. This refers to the first two steps being the most important.

Split Step: Jump into First step

In Tennis before the first step takes place the athlete will normally do a jump in the air as the opponent is about to strike the ball. This is yet another example of using the stretch reflex to store and release additional elastic energy in the muscles to explode to the ball.

For this part of the classroom presentation we therefore looked at proper mechanics of the first step as it relates to the sport of Tennis.

Let’s look a bit closer

For me the first step is a powerful step in the intended direction. By step I mean a powerful contraction of the quadriceps and glutes often using a pivoting type action. However in Tennis, prior to this step there will usually be one of a few things that can happen before this powerful step takes place.

- The body jumps in the air and the feet land simultaneously known in Tennis as a ‘simultaneous split step.’ This is usually followed by a pivoting action of the foot- the way most coaches would like you to teach it!

- The foot/hip nearest the intended direction opens up slightly- common when you are in motion or have read the situation- is usually part of a ‘staggered split step’ (see below)

- The foot nearest the intended direction falls under the body in the opposite direction- common when you are moving from a very wide foot position

- The foot furthest away the intended direction pushes in the opposite direction to the ball known as a ‘dig step’- common when your feet are quite close together or you’re quite upright and are reacting to the play.

Staggered Split step

I wanted to focus on the staggered split step as it is similar to the plyo step/dig step but requires explanation

For me a plyo step or ‘dig step’ is a reflex response to a random signal to move. The ‘staggered split step’ is applying the same laws of equal and opposite forces but it is more of a ‘conscious’ push with the foot furthest away from the direction of travel. This happens when you read the game and can anticipate the direction of your first step. The dig step will come into play when you have to react to the direction of the ball and is a reflex. Somewhere between the two is the simultaneous split step where the athlete is able to pivot off the foot-like most coaches will want you to do in your first step!!

If you watch the clip carefully of Andre Agassi moving laterally above, you will see his left foot slightly hits the ground before his right. This is known as a ‘staggered split step.’

Multi-directional Speed

We looked at a Pro Agility Shuttle (5-10-5) which focuses on the explosive change of direction.

Key points:

Again credit goes to Brian Grasso of the IYCA who showed me the 4 steps to a good body position for changing direction.

1. Feet slightly wider than shoulders or ‘outside the box’ made by the shoulders and hips.

2. Feet turned slightly toward direction of travel

3. Hips back

4. Shift weight towards inside leg closest towards direction of travel

Then we looked at how this would apply to the tennis court

Notice how after hitting the ball Djokovic is initially out of balance and in no position to effectively apply the forces in the correct positions. But then he quickly reorganises his body so he can find the correct position to push himself back towards the centre of the court.

Practical

After about 40 minutes in the classroom going through these videos we went on to the court to look at some drills to develop the three types of Speed of the 3 S APA Training System (Straight ahead Speed, First step speed and Multi-directional Speed).

I will upload some videos to give you a taster in another blog but if you can’t wait to then, then you can get more information on these topics and over 200 video clips of drills at my new EBOOK. Click HERE for more details.

In the mean time I want you to do three things:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons at the top and bottom. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

I’ll read the comments. I’ll think about them. I’ll plan the entire future of this blog around them.

Daz