Perception is the new frontier of athletics?

Perception not practice makes perfect

I have been wanting to write about this for a few weeks.

Lately there has been a lot of press again about the next ‘new’ predictor of athletic performance. It seems deliberate practice has been replaced with new hype on the importance of ‘perception.’ If I sound a little derogatory I apologise but for those of you who know me, you will appreciate I am very reluctant to give too much kudos to one aspect of performance when it comes to predicting success in elite sport.

Is my child going to make it? Can it ever be any better than a 50:50 best guess?

Check out the full article here on a A new meta–analysis in Perspectives in Psychological Science which looked at 33 studies on the relationship between deliberate practice and athletic achievement and found that practice just doesn’t matter that much.

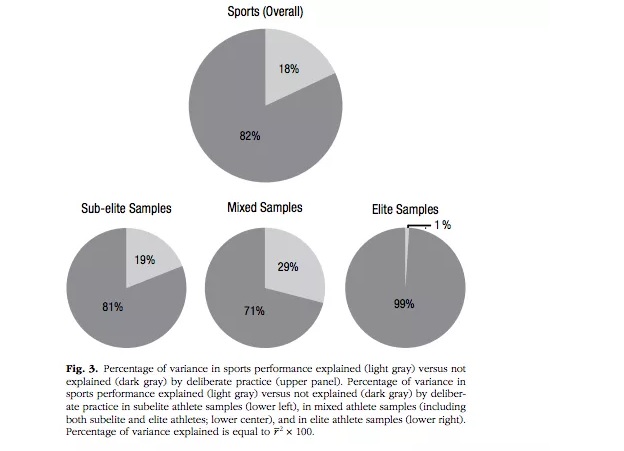

I really like the fact that it summarises that practice accounts for only 18% of the difference in athletic success between elite and sub elite athletes. Basically it is saying that practice time only accounts for 18% of the reason why someone is better than someone else.

”Even more simply: Some people are just better at sports than others, and the difference cannot be made up by practice alone.”

Personally I have always been comfortable with this idea that talented athletes just pick up skills sooner. Talented athletes have faster learning rates, a concept I like to compare to internet download speed- some athletes just dial up and process the information faster. Some people are just slow learners.

One thing it does say is: “We have so many factors within a person that can contribute to [athletic performance] — different genes, different cognitive abilities, different physical attributes. All of those things are important and interact with each other. Which is why it is so hard to pin down what predicts performance.”

It’s this focus on cognitive abilities that I would like to comment on.

My caveat is that this is just one part of the development pathway, just like psychological and physical development, cognitive development needs to be addressed too. Click here for the discussion of the programming components that should feature in an appropriate neuromuscular training programme.

In reality you need to create lots of stimulus to test the cognitive abilities of developmental level athletes and one of the easiest ways is to play other sports. ”The current evidence supports the contention that children should be encouraged to take part in a variety of sports at levels consistent with their abilities and interests to best attain the physical, psychological, and social benefits of sport.”

Different sports place different demands on your decision making processes- the trajectory of different shape and speeds of balls (tennis ball versus basketball versus rugby ball), opponents, dimensions of pitches, and time available to make the decisions. But there is nothing wrong in my opinion in training contextual decision making by trying to simulate elements of the sport while doing speed.

That’s why decision making features early in the APA speed development pathway (See Level 3- which is typically the time around puberty).

Table 1. APA 6 Stages of Development

|

Girls |

Boys |

||

|

Fundamentals |

Level 1 |

6-8 years old |

5-9 years old |

|

Learn to Train |

Level 2 |

8-10 years old |

9-12 years old |

|

Train to Train |

Level 3 |

10-12 years old |

12-14 years old |

|

Train to Train |

Level 4 |

12-14 years old |

14-16 years old |

|

Train to Compete |

Level 5 |

14-16 years old |

16-18 years old |

|

Train to Win |

Level 6 |

17 years old+ |

19 years old+ |

See below for how the skills are first taught in isolation then once we establish stable efficient motor skills we then add the performance layer where we test them under conditions of complexity (link skills together) and also decision making.

| Speed Focus | |

|

L1 |

Isolation: Marching (speed), turning and stopping (agility) and fast feet (quickness) |

|

L2 |

Isolation: Basic starts (speed), cutting (general agility), footwork (sport specific agility) and multi-directional sprints (quickness) |

|

L3 |

Combinations: focus on linking together various footwork patterns/directions. Can also include obstacle courses that weave together different challenges one after the other. |

| Randomisation: challenge the decision making skills of the athlete using tasks that focus on a specific aspect of speed. Can also include use of chaos games. | |

|

L4-5 |

Intensification: challenge the athlete to overcome external resistance |

|

L6 |

Accumulation: Train Anaerobic System using multi-directional running jumps |

This is not to say we won’t do any decision making prior to puberty. Of course we do- it’s just to highlight the emphasis.

So what does this mean for training?

The training above continues to fuel the flames of an ongoing debate about the relevance of programmed change of direction mechanics as performed above. There is no stimulus to respond to and its just pure turnover training or ‘fast feet.’

I say- yes that may be true but it is still presenting a neuromuscular overload. But what are the advocates of another approach saying?

Train decision making component of movement. It could mean the use of things like FitLights which were famously used by the likes of Paul Scholes at Manchester United (see here and here)

But while I really like the concept of training reactive agility, I don’t think this is the holy grail of athletic performance that some people are making it out to be! The physical components referred to in the video above take time to develop, both in terms of kinetics (magnitude of force- capacity) and kinematics (direction of force-mechanics).

Here is a great video highlighting the importance of coaching correct kinematics in change of direction mechanics. I think this is vital and I hope coaches value its importance. Pay attention.

I’m a bit concerned that former Manchester United Power development coach Mick Clegg said Christian Ronaldo never lifted heavy weights as it would detract from the skill development work. My standpoint is that a programme should always be balanced and work aspects of the entire Force-Velocity Curve.

What do you typically see in Football?

I think there is a lot of good quality ‘quickness’ work on display here. Is it explosive? No. Disagree? Check we are using the same definition of ‘explosiveness.’ See a great article here from Science in Sport on the Force-Velocity curve and further explanations of training methods to develop it.

I still think all sportmen and women should be doing strength training and as long as it is planned properly you need to do heavy weights to guarantee you are overloading the Force component of the Force-Velocity curve, as well as doing moderate weights, at moderate speed, and fast movements at fast speed, including weights, bungees, and even bodyweight fast feet drills.. There you go- variety is the spice of life. Rant over!