What is athleticism and have you got some?

This week I have had the privilege to guest lecture at the University of Hertfordshire Sports Studies 1st year and 3rd year coaching modules. The topic was ‘The Art of Coaching: How to Communicate Effectively.’ For ideas on this topic feel free to read the previous blog on this topic.

One of the great things about watching other coaches is you can pick up some cool ideas for drills – a lot of the drills I saw were games based. This was great for me to see as I often tend to coach through technical drills and I feel I need to open up the drills sooner into challenges/games which include more decision making. The use of decision making was the inspiration for this blog, and was something I referred to a lot in my recent workshop.

Workshop Review

This weekend I presented on the second in the APA series of workshops, ‘Coordination and Strength training for Sports.‘ Because the majority of attendees were tennis coaches and the focus of their work was with young athletes we focused on the area of skill, specifically coordination. Later on I’ll come back to the role of decision making.

I wanted to achieve a few objectives in this workshop:

- Define Athleticism and Skill

- Discuss theoretical concepts of skill acquisition

- Show some drills to develop Skill

Definition of Athleticism:

This was our start point……..I then wanted to build on this concept of ‘movement’ and go a step further by talking about movements that involve constant shifts in someone’s centre of gravity.

This was where we discussed AGILITY.

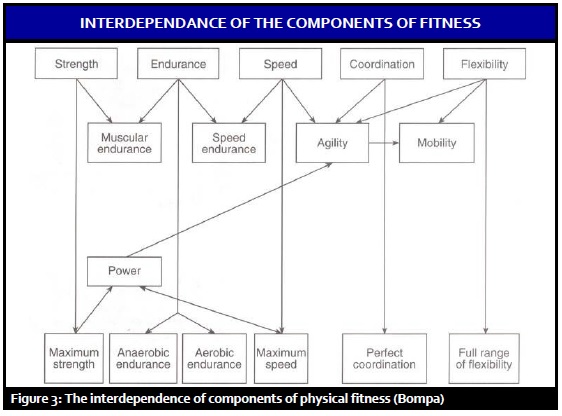

I wanted to highlight that the components of Fitness in the centre of the diagram are higher order components that are built on the foundation components of Fitness around the outside of the diagram. If you look closely you will see that there are more arrows pointing back into Agility. Agility is an expression of:

- Power

- Speed

- Coordination

- Flexibility

In today’s workshop we focused on the ‘Coordination component.’

Definition of Skill:

I introduced the concept of Skill with it’s sub-components (at APA we also talk about Balance and Reaction Speed)

- Balance

- Coordination

- Reaction Speed

Balance:

- Static Balance- drills where you are stationary.

- Dynamic Balance – where you are in motion and have to bring yourself to a stop either in response to a cue or following completion of a movement sequence.

Coordination:

- Locomotive and Manipulative.

- Locomotion- movement skills that are designed to get you from A to B.

- Manipulation- movement skills which involve the sending or receiving of objects such as kicking/striking/throwing/catching

Reaction speed:

- Response time is the sum of reaction time and movement time. Focus on skills that challenge reaction time. It doesn’t necessarily have to involve locomotive tasks – in fact in the beginning it can simply involve tasks that can be performed stationary.

- Simple reaction time is the motion required for an observer to respond to the presence of a stimulus. For example, a subject might be asked to press a button as soon as a light or sound appears. Mean RT for college-age individuals is about 160 milliseconds to detect an auditory stimulus, and approximately 190 milliseconds to detect visual stimulus.

Theoretical concepts of Skill Acquisition:

We can all agree on one thing – whatever coaching philosophy we have when it comes to developing movement skills – the outcome we all want is a permanent change/improvement in the way the (tennis) athlete moves on the court. We want to directly or indirectly enhance the quality of movement where it actually counts- on the field of play.

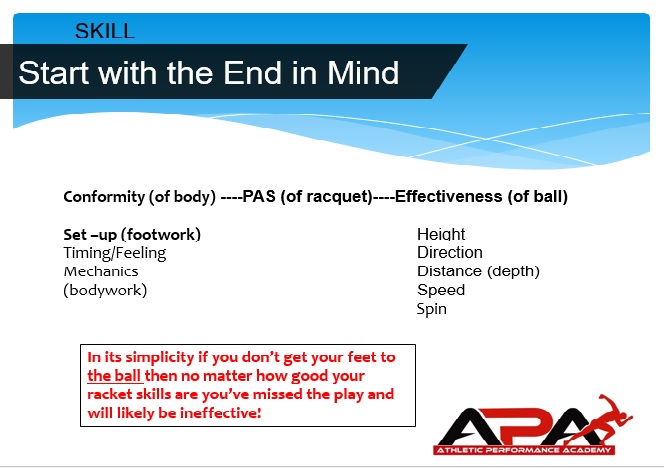

The slide above is basically saying that while the racquet skills (sport skills) are critical to getting the outcomes you want in terms of effectiveness of ball, they need to be supported by effective footwork (movement skills). It’s because of this that I wanted to talk about methods to develop movement skills that transfer to on court performance. Therefore in the workshop presentation and practical I discuss different aspects of Skill development.

Perception Skills:

In the video below there is a strong case made for the need to train cognitive/perceptual responses to a stimulus in order to call it Agility training – otherwise it is just change of direction. This is why the reaction speed component of skill is something that we bring in early to challenge the athlete’s decision making ability as a precursor for Agility training.

Video: courtesy of Sport Science Collective

It says there is recent research to suggest that there are no significant difference in change of direction test performance between higher and lower level athletes.

It goes on to say that neither strength/power training or change of direction training enhance Agility.

It highlights that Agility training includes technical components such as foot placement and body lean and posture, as well as physical components such as core strength, straight speed, and leg muscles qualities (Strength, Power and Reactive Strength)

Yet despite the physical components research indicates that training for strength and power does not enhance agility.

So how do we train for agility?

The cognitive component is highly trainable through use of drills involving decision making and small sided games.

ie., Add a perceptual challenge to a technical task- such as first step speed drill in response to a visual cue

Video: courtesy of T&K Tennis Team Tunisia

Technical and Physical Skills:

But before we all hurry to our play book of games I don’t think we should underplay the role of the other components. The technical components relate to kinematic aspects of skill which can be coached and corrected with almost immediate technical feedback (teaching). The physical components relate to kinetics aspects of skill which require longer term practice to overload the muscular skeletal system (training). I see the cognitive components as just another aspect of skill development where you can perform the skill under decision making pressure (performing).

Video: courtesy of E.M-Sports Science

Then the final expression of the skill is the actual sport itself. So at APA the skill development model for speed might look like this:

Basic 1– teach the technical components of foot placement and body lean in more stationary positions (see video above- E.M-Sports Science)

Basic 2– teach the technical components of foot placement and body lean in more dynamic positions

Basic 3– train the technical components using combinations of movements (complexity) and decision making pressure (add the perceptual component- see the video T&K Tennis Team Tunisia)

Advanced– train the physical components using overload stimulus (resistance) and later repetition (fatigue)

All all times the final skill can be tested in games based environments to keep engagement levels up and measure progress

Final point: Implicit and Explicit Teaching Methods

An effective coach will use drills that firstly engage the athlete – we want our athletes to be ENGAGED by the task, whether that be a maximal effort, or a really difficult challenge in some other way. Sports related skills are what excite the athlete so we need to find ways to tap into that sort of feeling in S&C with engaging tasks! What makes sport so compelling is the competitive element, the chaos and the constant mental stimulation and decision making!!

Focus on the Outcome and the Process takes care of itself:

There then needs to be a clear OUTCOME, the INTENTION– The athlete is clear on what they are trying to accomplish. What do you want them to be able to do? In tennis this is obvious, get behind the ball and beat the bounce; it’s especially important to have the right intent in that situation because intent drives visual focus!!! But what about in S&C?

- It could be a time based goal – beat your best time, or win a race.

- It could be to catch a ball without it bouncing twice or dropping below waist height

- It could be a distance based goal – jump or throw a certain distance

- It could be a reps based goal- achieve a certain number of reps in a certain time

The we come to the PROCESS- the ATTENTION

This is an area I feel I may have over coached.

Focus on a few External cues – where you want to get your body to (external) rather than how to get there (internal).

I feel I have put too much emphasis on drawing the athlete’s attention to a lot of internal factors (such as range of motion, control of the load, bracing, breathing and alignment/foot position). This creates a high level of awareness of what the BODY is doing in relation to the ground. The coaching is very Explicit. It might be better to select a FEW KEY COACHING CUES.

I still feel technical components need to be worked on without a perceptual challenge in many cases, however. For example, if the athlete appears to lack the coordination to organise themselves both with or without a perceptual stimuli. It may also have a use in developing symmetry in the body. But I think we need to bring in perceptual challenge too- probably a lot sooner than I have done and it is more engaging for the athlete.

The video below is an example of a common approach I have taken which is entirely focused on awareness of what the feet are doing. I actually define the spacing of the feet with physical barriers. The opportunity for Discovery Learning is eliminated because I am telling them where to put their feet. But my rational has been that it is effective coaching because the hoops/hurdles coach the drill for me by forcing the athlete to use the correct footwork. This certainly works better than trying to ‘tell’ them where to put their feet – or do it by copying me.

But there is no cognitive component in terms of visual stimulus to respond to. When we actually play tennis we don’t want to be paying attention to our feet while hitting a ball- we want to focus on the ball.

The key thing here is the need to develop a ‘non-awareness’ strategy. We don’t want the athlete to pay attention on the task while it is in progress. Ives and Shelley (2003) advocate against athletes focusing on themselves – e.g. looking in a mirror/or at their feet – but would rather have mental effort directed towards strategies and cues relevant to sports specific performance (i.e., focus on the ball).

In the video below the athlete is practising a vertical jump but has their attention placed on a visual focus above them which gives a better indication of how they would move in an open sports environment. The video above could simply be performed with the athlete moving to hit/catch a tennis ball.

Start with the End in Mind:

Secondly- I feel I have been guilty of breaking skills down often without firstly examining how close the athlete is to performing the final skill. I came out of the Whole-part-Whole school of skill acquisition. But from conversations with colleagues it might be said that the most effective coach is the one that gets the athlete to the final skill the quickest. Only break down if you have to, and even then consider trying keeping the final skill but just make it a little bit easier (e.g slow the movement down or give more time etc).

So if someone appears to have a poor process- first check you have given them a sufficiently challenging outcome to reach and give them a few goes to achieve the outcome before you decide to break down the process. It’s amazing what someone is capable of if they are challenged to achieve the final skill. Also try to give them as few cues as possible to make the changes- you may find that you can draw attention to just a few simple cues to make the corrections without a drill rather than having to stop the drill and break it down.