There’s no such thing as a sport specific strength exercise!

Okay folks, this is about my twentieth post on the topic- each time I move forward with my thinking on sport specific training.

Today’s blog has been inspired by my Tennis colleague Ruben Neyens, who was on a conference call with me and a few mutual friends where we were talking about strength training and specific exercises for Tennis. Ruben threw out a few questions/observations which are pretty typical of the Tennis coaches view of strength training.

Follow Ruben: @ruben.neyens

Follow me: @apacoachdaz

Statement 1: In Tennis it is often the case that the player needs to be able to execute the skill in quite challenging positions (uncomfortable/awkward) on the stretch, low or high positions in relation to usual centre of mass etc. How does strength training prepare the player for that?

Statement 2: The gym is quite a closed environment, where movements are pretty much the same every session with not much variation in movement. This compares to tennis where you never really hit the same forehand or backhand twice in a row and it’s quite open. How does strength training prepare the player for that?

With those questions posed, Ruben actually had to leave the meeting and I promised him I would give him thoughts on this on a blog….so here goes.

Enter Frans Bosch…well not literally, but I felt that these statements needed the attention of a man far smarter than me, so I pulled out Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrated Approach

In case the mere sight of the front cover has got you rolling your eyes because you’ve heard he is ‘anti-strength training‘, stick with me because I’m a big proponent of doing heavy weights but I want to give a balanced view of things. He makes some observations that are difficult to refute – such that the ‘strongest’ athletes are by no means always the fastest sprinters, and evaluation of training always shows that, in technically somewhat complex sports, increased force production does not automatically lead to improved performance.

On a side note, I one day hope to release a volume of work that challenges the status quo like Frans has. I regard myself as somewhat of a Newtonian when it comes to my thoughts about strength training- it’s all about Force. But Frans has definitely challenged my ideas about the role strength training in the gym has in transferring to sports performance.

Within the first 10 pages of his book Frans has already cast doubt over my entire reductionist approach to athletic performance and states that ‘a highly reductionist approach to these aspects will not take proper account of the dynamics that shape movement patterns.’

Disclaimer: throughout the book you need to view it through a lens of improved sports performance. He is making a case for the kind of strength training approaches that will transfer to improved sports performance (better movement technique in the competitive exercise whether that involves running, jumping, throwing etc). As we will see later, there are plenty of reasons to strength train the traditional way, even if it doesn’t cause direct transfer to sports performance. So just bear in mind his book and this blog is about movement and role strength training plays in improving it.

Movement patterns

Movement is composed on the basis of a flexible set of movement rules that are generally applicable and can filter and shape incidental adjustment to the demands of the environment.

The precisely taught lifting techniques will not be remembered, for it is not universally applicable, if only because the objects that are lifted in everyday life all differ in shape and weight. Stable yet flexible movement patterns do not develop by learning techniques precisely but through self-organisation from complexity.

Already I can imagine Ruben nodding his head because when you speak to a tennis coach they are talking to you about a movement problem so it stands to reason they would also see the traditional gym environment as being too inflexible to help them with their tennis player’s movement.

Yet one common word we share in our coaching toolbox is ‘technique.’ A good description of technique in a sporting movement is therefore not one that prescribes ideal joint angles, but one that describes universally valid underlying principles of the movement and leaves room for variants that develop from self-organisation and are related to the individual properties of the body.

The role of strength and speed in movement

During the intermuscular cooperation, the amount of force is no longer the most important feature of good movement – what is crucial is the timing of the production of force. The more contextual a movement pattern becomes, the more strength and coordination become a single entity.

Likewise, the speed of action of muscle fibres only partly determines the eventual speed of contextual movements. It’s the timing (and hence coordination) that once again is more important. Speed is thus a function of coordination too.

A reductionist approach to movement- whether this means thinking in terms of categories such as speed and strength, or pursuing perfect technique in isolation – does not focus on the limits of sensorimotor links. Approaching sport specific strength training from a purely physiological angle disregards the way in which the learning system organises movements and transfers between them.

Role of Coordination

Sports coaches intuitively sense that strength training will produce the best transfer if the movements are performed in movement patterns similar to those in the sporting movement. There appears to be a close connection between strength and coordination.

Strength training is coordination training with resistance

Want proof? Look at what happens when a beginner enters the gym for the first time. During the first few weeks the muscles will not get stronger, nor will they increase in size. Performance will improve when there is improved cooperation between the agonist, antagonist and synergists (improved intermuscular coordination).

The Sweet Spot

Traditional strength training strategies focus on improving the qualities in the contractile parts of the muscle. More modern approaches put far more emphasis on the role of the central nervous system in force production. A synthesis of the two approaches would seem useful.

Role of isometrics

I’ve written about this extensively in previous blogs – but for now I will just remind the reader that a recurrent theme throughout the book is isometric contraction of the contractile elements which is a feature of many contextual high speed sporting movements, and differs greatly from concentric and eccentric actions, described in plyometric exercises. This allows the elastic component of muscle to be stretched, and creates forces many times that which the body could be capable of producing concentrically. This is because there is no eccentric-concentric action in the muscle fibres when loading and unloading elastic energy during throwing and running. The muscle fibres act isometrically, so that the musculotendinous units lengthen and shorten through stretching of the elastic parts.

Daz note: this muscle action can only occur in actions where the knee angle does not exceed 20-25 degrees. Therefore we are talking about specific types of jumps, such as single leg take offs, very reactive double leg jumps and high speed running.

Central Nervous System Control: General Exercises

Traditional strength training focuses on the role of the brain and spinal cord in controlling all muscle contractions by sending messages to the muscles in response to sensory input. Large intermuscular patterns – the building blocks of movement – can be controlled this way. This could be another way to describe ‘general’ exercises in the gym.

When thinking about movement patterns in sport, such control at spinal cord level has little significance according to Bosch. It is still very difficult to translate that into intensive contextual movement, especially in the upper limbs. However, Bosch notes the movement of extension of the arm synchronous with rotation of the trunk around the longitudinal axis (used in punching) is one such general movement that is a generic building block of movement that can be used in such varied patterns as shot putting, boxing and arm entry in freestyle swimming.

Bosch talks about in sporting movements having to improvise and adapt it to the constantly changing demands of the environment. Now in order to do this, instead some are adapted but others remain unchanged. Seen in this light, strength exercises are very suitable for improving unchangeable components of skill.

This paves the way for Fran’s terminology of ‘attractors’ and ‘fluctuators.’ Higher parts of the system (brain and spinal chord) ensure the general, more abstract rules of the movement. while specific muscle actions and ranges of motion tend to develop from self organisation of the musculoskeletal system (peripheral nervous system).

So going back to statement 1 we can say that indeed in Tennis there will be great variety in the position players find themselves in. The key thing is to identify the attractors and fluctuators present in the movement. An attractor will be present in all variations of the movement (think of it as a non negotiable or a key performance indicator).

Common Attractors:

- Head position

- Arm abduction at an angle of about 90 degrees when throwing

- Contact point on the swing

Common Fluctuators:

- Trunk side flexion

- Knee flexion

- Pelvis rotation

A few typical universal attractors found in most running based sports include:

- Hip lock during running

- Swing leg retraction

- Foot plant from above

- Positive running position

- Head still

- Upper body initiates movement

- Extend trunk while rotating

- Distribute force while decelerating

Applications: Analysing athletic movement and identifying the stable components of the movement are key steps in devising a meaningful strength training programme. Strength training needs to take into account the laws of motor learning.

In sports in which technique has a decisive impact on performance (I think Tennis qualifies), it may be useful to gear strength training to coordination training as far as possible.

Ask yourself:

- Is the quality of the explosive sporting movement limited by the demands that motor control makes on its performance? How will the degrees of freedom be controlled in an environment of attractors and fluctuators?

- Under what conditions can strength training help shift that limit?

Role of Motor Control

This section is going to allow me to comment on statement 2, which was making the comment that the gym environment is very closed.

Frans observes that:

In explosive sports, performance is largely limited by the requirement that the movement must be controllable

A movement is only controllable if it can withstand external and internal pertubations. The main internal pertubation is fatigue. One of the most important mechanisms for controlling movements and making them robust is the influence of cocontractions in what is known as the speed-accuracy trade off.

When agonists and antagonists contract at the same time, they keep each other more or less balanced. The right balance is thus struck by a number of muscle properties that are not subject to neural control.

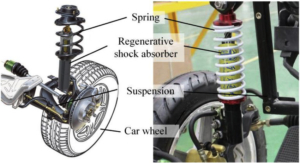

The effect of these mechanical properties is known as ‘preflexes,’ (mechanical muscle properties that influence the eventual performance of the movement without involving the central nervous system). The action of preflexes within cocontractions forms the basis for muscles’ self-organising ability. The effect of preflexes can be compared to the action of shock absorbers in a car’s suspension system.

The central nervous system emits the signal for the powerful cocontractions, and the correct movement is then largely ‘organised’ by the muscles themselves. One major benefit is that response time is nil (0 milliseconds), so you can make contractions when the central nervous system has insufficient time to intervene.

Now because this is a protective mechanism for the joint, this comes at the expense of speed of movement. This is important because it will for example, protect the shoulder when a child imitates an adult and tries to throw a ball overhead for the first time. The mechanical properties of the muscles will adopt a 90 degree abducted arm almost automatically to take the pressure off the shoulder joint.

It also has a positive effect because it reduces muscle slack. Muscle slack limits the intensity of movement. Reducing it by creating pretension with the help of contractions reduces this limiting effect on the potential intensity of movement.

Therefore, in sport where high speed high intensity movements take place (think sprinting and take offs in jumping, as well as ballistic throwing/striking) the limit on performance is probably determined by the demands that motor control makes on intensive movements. This limit, which occurs before the limits of the healthy central nervous system are reached, serves two purposes:

- keeping the movement controllable in an environment in which several unforeseeable pertubating forces will act on the mover

- protecting the athlete from injury by limiting the load on the system.

Before We Throw The Baby Out With The Bath Water

When you read the book carefully, Frans states on several occasions that traditional strength training (think maximal strength) and his approach (coordinatively complex ones with a light weight) should be blended. With everything that we have spoken about until this point we are about half way through his book!

Now we have gone through the theory, we finally get to the strategy………but I’m probably going to get into the meat of the strategy in a part 2, so for those who have stuck with me to this point I’ll give you a quick overview now.

Implications for Strength Training

Training methods should be designed to provide a reserve of load capacity to protect the body during high intensity movements.

Two strategies for strength training emerge from this idea:

- Raise Force Production by muscles as far as possible in the hope that the submaximal (‘good enough’) level, as well as the robustness of the movement, will increase together with the maximal level. The maximal level raises the submaximal level along with it, as it were. This strategy approaches strength training in terms of contractile properties of muscle.

- Increase the Robustness of the movement so that the ‘good enough’ level will shift towards greater force production during the athletic movement. The submaximal level then shifts towards the maximal level without the maximal level needing to rise. This strategy approaches strength training much more in terms of movement technique than the first (motor learning strategy).

As previously stated, in practice there will almost always be a blend of the two strategies. But with the understanding that motor control places an importance on robustness of a skill (adaptability), it makes clear why in many cases there is no reason for explosive athletes to try and lift heavier and heavier weights within strength training.

‘Strong enough’ is something most athletes can easily achieve, and it is pointless to invest in anything more. Making movement patterns more robust through strength exercises, is the most useful strategy for elite athletes to develop their skills.

Frans goes on to say that:

The problem with many strength exercises is that they lack a clear intention

I’m going to finish this blog post by summarising the last 30 pages of chapter 4 (of 7) and save the exercise selection part for another post.

Our body organises our movement solutions in clusters of similar intentions, rather than clusters of similar muscle activity. Movements are above all intention-orientated. The body does not think in terms of processes but in terms of the results of the movement. We all like a target to aim for! This is one of the clear benefits of Olympic lifts is that there is a clear end point of where the bar needs to finish and within what time, if you execute it correctly.

Furthermore, if attention is focused outside the body on features related to the movement, the movement and motor learning processes will be controlled more effectively. The reason why external focus works better than internal focus, is quite simply that external focus concerns the RESULT of the movement (the basket the ball has to go into, a stable landing in gymnastics, the box the serve has to land in). Most coaches direct attention internally and no where more so than in the gym doing strength training. The body couldn’t care less about the processes of how to lift weights, it’s only interested in the result. So give more feedback on knowledge of results (outcome) rather than knowledge of performance (process).

Now before you get alarmed this can simply mean giving the athlete a sense of the start and end point of a movement and letting them figure out how to get there. This is important because research shows that movements learnt with a great deal of augmented knowledge of performance feedback are less stable and less reliable especially in stress situations!

The gym is often seen as a boring place for athletes because every rep is the same. The learning process will not be greatly stimulated if the sensory information is well known. Repeating the ideal execution of the movement in a standard setting does not lead to chaos- VARIATION in the execution of the movement in unfamiliar settings does.

This monotony within strength training has an adverse effect on the training effect. It also impairs coordination transfer, and so it will not be easy to organise strength training in a way that creates the condition for such transfer.

The Movement Paradox: Finding Generalised Rules Through Variability

I want to finish by repeating a statement I made at the start: stable yet flexible movement patterns do not develop by learning techniques precisely but through self-organisation from complexity.

A principle of movement will be learned and automated more quickly if it is GENERALLY valid and hence can be applied in many different movement patterns. It is absolutely essential to seek generally applicable principles of movement. The ideal way to do this is variation in training (repetition without repetition), which should play a part in the learning of strength training techniques.

The learning system is very interested in general rules that can be applied in many situations. These basic components of the movements have attractor characteristics. They are STABLE and ECONOMICAL. Variable training can separate the stable (i.e. generally applicable) components of the movement from the changeable, fluctuating (ie incidental) ones.

Final thought: a movement can only be truly mastered if it is to be executed stably as well as in changing environments. Performing well in competition depends on this combination of stability and adaptability. In the run up to competitions it may be therefore useful to retain some variability in training.

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM