My thoughts on the Triphasic Method – Part 1

I’ve been meaning to write this blog post for a while, in truth the book’s been sitting on my book shelf for over a year but I’ve finally got around to reading it properly and I have to say it wasn’t what I was expecting- in a good way.

If someone had asked me before reading the book if I knew what the triphasic method was, I’d probably have said: ”yeah, it’s a strength training programme which emphasises several weeks of each type of muscle contraction- eccentric, isometric and concentric.”

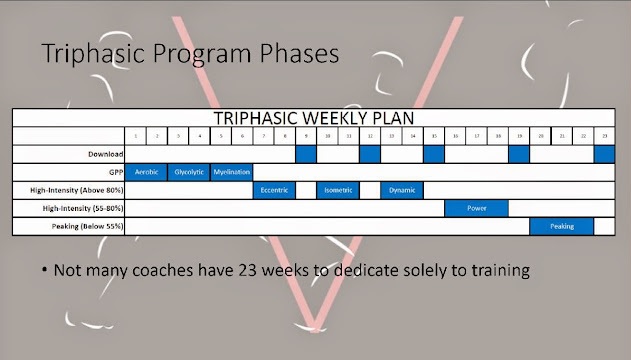

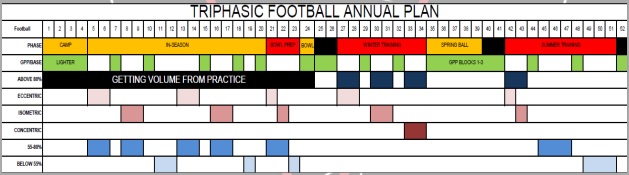

Having read it I’d still say that’s what it’s about but I learnt A LOT more besides. The triphasic method is only part of the entire training system Cal uses; the triphasic method refers to the ‘strength’ phase (also known as the ABOVE 80 block), but there is also a ‘power’ block (55-80) and a ‘speed’ aka ‘peaking’ block (LESS THAN 55). All in all this represents a period of approximately 12 weeks from start to finish (not including deload weeks).

Overview

Triphasic training is a system devised by Cal Dietz in the 2000s and resulted in a book being published about it in 2012. The goals of triphasic training are:

- Transfer of Training – the ultimate goal

- Stress the body optimally

- Prevent the body from being pulled in too many directions

There are three components of triphasic training:

- Triphasic muscle action

- Modified Undulating periodisation

- Block training model

Below is a intro to some of the topics/statements made that caught my attention, so if they interest you too then you’ll want to keep reading:

Muscle physiology

- Sports are identical at their physiological core

- All dynamic muscle action is triphasic – that’s why most approaches to training explosive power (concentric biased) are dead on accurate one-third of the time ?

- Triphasic method is a foundational [strength] training method applicable to all sports – as all sports have the same physiological nature of muscle action taking place during dynamic movements

Periodisation

- Modified undulating periodisation is needed for drug free athletes to recover from the stress

- Block periodisation is better than concurrent (complex parallel) periodisation

- Block periodisation is better than traditional linear periodisation

? There was a really interesting discussion about the type of periodisation that is best suited for an elite athlete who needs a lot of stress and the best way to plan that, so I’ll definitely cover this later ?

Strength & Power

- The key to improving sport performance isn’t about who is the strongest; it’s about producing more force in less time- who has the narrowest V wins!

- This results when an athlete can absorb more force eccentrically- meaning the body can’t generate more force than it can absorb maximally

- The neurological system is stimulated at its highest level at loads that attain the highest power outputs

- The most important component of power, in relation to sports performance, is time

- Strength comes before power- don’t put the cart before the horse

? The general principle of having a strength base is nothing new but the focus of getting eccentrically and isometrically strong and how that sets up a concentric phase was very thought provoking ?

Loading parameters

- Loads chosen for strength block would ordinarily correspond with an RM of 4RM, 2RM and 6RM respectively.

- Loading parameters within strength blocks are focused on preservation of power output – therefore to ensure the quality of work remains high, sets in the ABOVE 80 BLOCK are limited to singles/doubles for medium day (82-87% 1RM), singles for high intensity day (90-97% 1RM) and three to four reps for low intensity day (75-80% 1RM).

- In the 55-80 BLOCK it is possible to train high force at high velocity- due to addition of a powerful SSC!

- In the BELOW 55 BLOCK sets are based on time – as opposed to performing a prescribed number of reps

? Probably the last points on the strength loading parameters were the ones that really stood out for me so we will cover this in a little more detail below ?

Matt Van Dyke wrote a Powerpoint Presentation on Advanced Triphasic Training Methods so it’s definitely worth a read if you want more specific info. I’d also check out this article from William Wayland who talks extensively about Oscillatory Training Methods– it’s not something I have used before but it part of Cal’s peaking block.

One thing to state having read the book, it is clear that the three phases I have mentioned (strength, power and speed) follow a GPP phase which is not discussed in the book. So I can’t really comment on the specifics of what Cal might recommend to do prior to starting triphasic training.

I’m just going to add a bit more detail to two specific areas that peaked my interest while reading the book. I’ll focus on Periodisation in Part 1 and Loading parameters in Part 2.

Periodisation

The triphasic method is focused on stressing the body optimally. Athletes do need to be stressed at the highest levels. According to the block training model, that stress must be focused on a specific performance parameter to ensure maximal adaptation of the athlete. If multiple forms of stress are applied to multiple parameters at once, the level of stress on each declines along with adaptation and performance.

In the early 1960s, Soviet athletes were mostly trained within a system they called the ”complex parallel” form of training. In more simple terms we can refer to this as a concurrent or ”mixed method” of training, where the athlete is exposed to several different means focusing on two or three parameters in each workout.

They may start with an explosive movement, such as cleans and then progress to a strength movement like a back squat and end the workout with hypertrophy work on the leg press. Cal makes the case that this mixed training approach is a sub-optimal way to improve the sports performance of an athlete. Although the ”total” stress of a mixed training workout can be very high, the amount of stress placed on each specific training parameter is very low.

E.g.

- Clean – 4×2 @ 125kg (85%1RM) – Speed-strength –> 1,000 kg VL

- Back Squat – 5×5 @150kg (80% 1RM) – Strength –> 3,750 kg VL

- Leg Press – 4×15 @140kg (65% 1RM) – Local muscular endurance –> 8,400 kg VL

If we take a fictional arbitrary number of 6,000 kg of training stress to see a positive adaptation you could see that the total stress of the overall workout is very high (13,150 VL) but the stress level required to see a positive adaptation only occurs for LME. The stress placed on the athlete, focusing on LME, decreases the total stress able to be placed on the other parameters, speed-strength and strength, resulting in no positive adaptations. This is a great workout if the goal is to improve LME but terrible if you are trying to build a powerful athlete.

Cal goes on to say:

- Mixed training only allows for 1-3 peaks per year. Due to the low levels of stress applied to each performance parameter, gains are slower and harder to come by, so you need ample time to develop and prepare for each

- Mixed training causes mixed results due to neurological confusion for the body – do you want me to powerful, strong, big or what??

- Mixed training doesn’t provide sufficient stimuli for high level athletes. The stress required to improve one’s performance in a target quality (e.g. strength) is so high that to try and improve another quality (e.g. speed) at the same time would be impossible.

Instead it is better to train one parameter at a time using a systematic approach accounting for the least pertinent parameters (those with lowest direct transfer to an athlete’s sport) first, with the most important parameters trained as close to a competition as possible. This approach is known as the BLOCK sequence approach.

❗The important point here is that only high level athletes need highly concentrated training loads to generate positive training adaptations. This principle wouldn’t hold true for novice athletes ❗

Early on in an athlete’s career, stress, any stress, will be new and likely cause a positive adaptation. Mixed training still provides enough stress to the athlete’s different systems to see improvement in various aspects of performance.

The sequence usually goes as follows:

- General Fitness – not specified in book (GPP)

- Maximal Strength (aka Triphasic) – 6 weeks (Accumulation phase)

- Power – 4 weeks (Transmutation phase)

- Speed (aka Peaking) – 2 weeks (Realization phase)

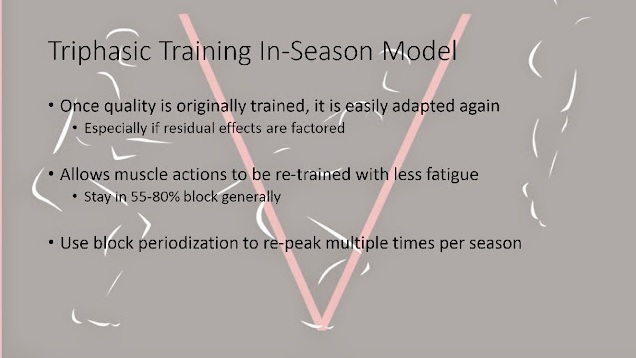

As stated above, not many coaches have the luxury of 23 weeks to dedicate solely to training (if you account for a 6 week GPP phase and several deload weeks) but if you are smart with the timing of the various parameters in the sequence you can use a block approach as part of a competitive season. More on this later.

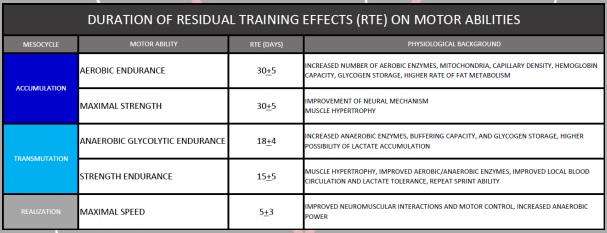

You can understand more about why it makes sense to train the qualities in that specific order by learning about training residuals. In a nutshell, the strength and aerobic qualities which you trained for 6 weeks in the accumulation phase, will have a training effect that will still last for up to 30 days after you stopped training them – which conveniently is the time you will go on to spend on the power and speed blocks. This means you will arrive at your peak with every quality still having had its training effect in tact.

Periodisation for Team Sports

As it was stated at the start of the Periodisation section ”once a quality is originally trained it is easily adapted again.” In North American sports they use the off-season (winter training) to apply the ABOVE 80 triphasic method (6 week strength phase) and then in-season most time is spent using the 55-80 BLOCK to ”adapt again.”

My thoughts on periodisation are as follows:

Let’s start with how we would approach a typical off-season training block.

Mixed training methods works best for novice athletes – most of my athletes fit that mold. I’m not doing mixed training through ignorance, I’m doing it because I believe that this is what they need. I’m all too aware that they will still get positive adaptations physiologically speaking but more than that, I want them to be doing a bit of everything all year around because they are in a teaching stage of development and I want them to practice the skills a lot.

In the example below, the loads used are clearly that of an advanced athlete. There is no way my athletes are getting anywhere close to those kind of loads. I want the clean and the squat in the same programme because I want them to learn the skill of how to do them better and that comes from frequent practice. Once their skill improves and they start requiring loads that are approaching their biological potential for force, it’s at that point that we can consider separating the stressors into separate strength and power sessions/blocks.

- Clean – 4×2 @ 125kg (85%1RM) – Speed-strength –> 1,000 kg VL

- Back Squat – 5×5 @150kg (80% 1RM) – Strength –> 3,750 kg VL

- Leg Press – 4×15 @140kg (65% 1RM) – Local muscular endurance –> 8,400 kg VL

Cal doesn’t use the OLifts in his triphasic method – rather he uses French contrast plyometrics twice a week and keeps the back squat in all the way through and simply varies the emphasis of the squat from one phase to the next (so you might be doing it super slow with a 6 sec eccentric in the first phase of the triphasic strength block and finishing with a super fast reactive squat in the speed block). I like this approach because for the most part he only tweaks things slightly from block to block and keeps the majority of exercises the same throughout. This makes it more clear what the effect of each block is as there is usually only one or two main changes – related to how the exercise is trained, as opposed to a complete overhaul of exercises.

At APA I approach training with our athletes using a similar approach to Cal, but it’s NOT A STRICT BLOCK model, it’s more concurrent. This means I have a thread of strength AND power exercises throughout any training blocks.

General Preparation:

I have a GPP 1 (Basic) and GPP 2 (Advanced) block. These are typically 3-6 weeks each. I use the General preparation phase to build strength qualities working up to maximal effort strength work for our Advanced athletes (5RM or a 3RM). I also build up aerobic and anaerobic capacities during these phases. I will be working on power qualities but these will be practised at a sub-maximal level, so using repeated jumps with external load (20-30% 1RM). Developmental athletes could be in these phases for extended periods of their time with us. Advanced athletes may only need to be here for a few weeks.

Specific Preparation:

In the SPP block I’ll prioritise Power and Speed (bringing them up to a maximal level also). For our advanced athletes who are already strong and hitting the strength KPIs we can focus more time on explosive strength. I personally still like to have a session that has a strength focus, and then one that has a power focus. If the focus of the workout is on strength, the power exercise will be a submaximal effort and the strength a maximal effort. If the focus is on power. the power exercise will be a maximal effort and the strength will be a submaximal effort, and performed more explosively. Our advanced athletes will be using vertical jumps with external loads (40-60% 1RM), and Olympic lifts for their maximal effort power work. Our less advanced athletes will still prioritise strength but we will increase the volume and intensity of plyometrics when appropriate.

On the statement ”mixed training only allows for 1-3 peaks per year”

I have never read that before. If anything, I would have said that the mixed approach is not designed to allow for a peak at all- it’s designed to maintain a high level of performance year round (well at least for the competitive season which can be many months) rather than peak for a specific event. The goal in my opinion, is to be at 80-90% of their peak all year round.

I will argue that most athletes cannot peak since they partake in intense practices and competition on a near regular basis and don’t have the energy capacity to exhibit their highest levels of performance. I would deem any and all of these individuals as “In-Season” athletes by definition. We can only really help athletes peak their fitness in the off-season where there is more time to dedicate to training, and should be treated as such.

Take my sport of tennis, for example. Tennis is a little different to team sports which build up to a weekend match and so still tend to get in at least 1-2 tough gym sessions mid week leading up to the match. I’ve found that in tennis, if they are in a tournament (and especially if playing singles and doubles) this might require them to play several matches a week and so the priority in between matches is RECOVERY.

If we regard tennis players as ‘in-season” athletes by definition, then how do we train athletes in-season?

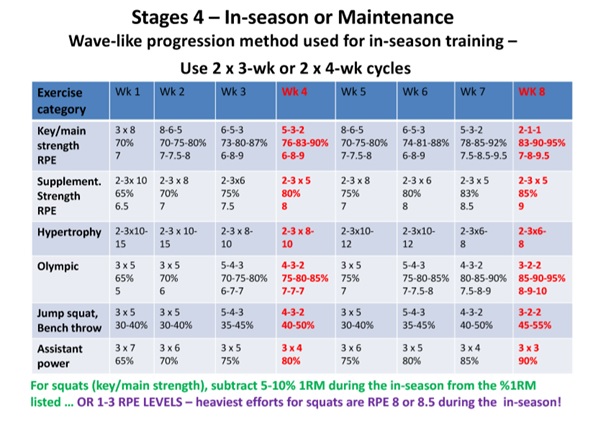

I would agree with Cal that staying in the 55-80 BLOCK is a good place to train in-season, if you have previously built up the foundational qualities in the first place. I know that Dan Baker used to have a 1x strength/size session and 1x power session in-season with his rugby league players. Another approach is to have a 2-3 week period of sessions focusing on hypertrophy and then 2-3 weeks focusing on strength/power.

Dan would also have a wave-like progression method for the loading to ensure that the players were only hitting close to maximum effort every 3-4 weeks (RPE 9+) and heaviest effort for squats in-season were RPE 8-8.5!

At APA we have a ”Force orientated” strength session and a ”Time orientated” strength session, the later using less external load with an emphasis on speed of movement. We use these x 1 week each as both a deload workout in between tough training weeks and also as a way to maintain strength/power during long tournament blocks.

But going back full circle, one of the original stated goals of the Triphasic method is to stress the body optimally. The APA philosophy is simple: give them what they need to keep improving! It’s nice to have a plan, a road map, but I’m not going to ”rush the journey” to get to the ”specific” work. Every training exercise has a training potential: the capacity to increase a specific aspect of fitness (e.g. strength) until that fitness quality reaches a certain level. Over time the training potential of the training exercise decreases.

So it makes more sense to use training exercises with the lowest potential first (which still elicit a training effect in a developmental athlete), followed sequentially by those that have a high training potential.

Give athletes the lowest dose of medicine you can until it stops getting them better! At that point you need to up the dosage!

I hope you found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM