How Much Do You Train Your Serve?

This blog is an update on the Vision of APA and a run down of the findings of the first Pilot Study looking at shot frequency data for junior elite tennis players.

I’ve mentioned previously that APA has the goal of being the ”Best Tennis S&C Team in the World” by 2025. This will be achieved in two parts. Firstly, by carrying out the most thorough tennis research project ever undertaken by an S&C company, with the goal of determining the physical determinants of elite tennis performance. I have been referring to this as my ”unofficial PhD.”

Secondly, by using the findings of the research to identify the most impactful training methods (APA Method 2.0) and undertake them with our athletes so they can best prepare for the current and future demands of professional tennis.

We have identified four areas of research interest:

1. Workload profiles – of training, simulated match-play and competitive tournaments

2. Serve – assessment of IR/ER shoulder rotation strength ratios, response to fatigue and relationship with serve velocity

3. Groundstrokes – assessment of rotational strength and power metrics and relationship with groundstroke velocity

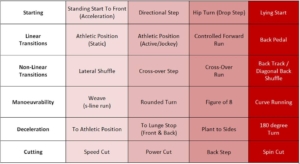

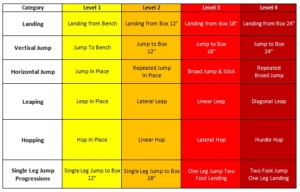

4. Movement – deceleration profiling, assessment of peak force and RFD of selected muscles (quadriceps and soleus) and relationship to movement velocities performed in match play.

Pilot Study #1 – Workload Profiling

As much as I would like to think that the strength & conditioning training in the gym plays a big part in helping players meet the physical demands of professional tennis, the bottom line is that the ”physical work” done on the court counts most. It’s the old adage of ”training tougher than a match.” So for me, the first priority was to gain some info on what is going on, on the tennis court.

For the first study I wanted to look at workload profiles of the players I work with, basically to see how the intensity of the tennis training compares to the [limited] data we have on workload profiles of pro players.

For those of you who are a bit more into the science, it’s worth noting that recently it has been shown that upper arm injuries and in-event treatment frequency increased by ≥2.4 times in both sexes at the Australian Open Grand Slam over a 5-year period (Gesheit et al., 2017). These kinds of injuries are a direct result of the mechanical loads imposed on the musculoskeletal system (especially the serve) and it is suggested that some measure of ball striking be considered to feature in an upper limb/body exposure (Reid et al., 2018).

The Game Insight Group (GIG) formed by Tennis Australia with Victoria University produce some cool stats on the Australian open using Hawkeye data – such as number of sprints (a sprint is a minimum of 5.5m travelling at least 4 m/s), Distance covered (km) and Hitting load (combines the number of shots a player has hit and how hard they hit them). Djokovic, for example will sprint on average 19 times a match, and in 2021 did 117 sprints across the 7 matches.

In all honesty, my ideal scenario would have been to look at workload profiles using intensity markers of the game such as Heart Rate and number of accelerations and decelerations if I had the technology (such as a GPS system and Heart Rate monitoring system). I think this kind of data would have best helped me to answer the question:

”How might our training and planning prepare players for match intensity & match volume experienced on the Tour?”

Given I didn’t have that technology, I opted instead to use Swing Vision (Player & Ball tracking app) to collect data from a selection of Junior National level players training at a full-time tennis Academy, for an entire week of training. I rationalised that this would enable me to carry out a qualitative analysis of shot frequency in training, and simulated match-play- which might give an indirect measure of training intensity & volume.

Furthermore, if I am going to follow up this pilot study with some research on training interventions to prepare the body for the serve and groundstroke demands, I figured it would make sense to first know how many times they perform these actions in training.

Therefore, the goal of this study was to quantify the number of strokes and the hitting intensities (rate of strokes per minute) performed by junior players during their on-court sessions over one week using Swing Vision.

What Did I Find Out?

Keeping in mind the old adage ”training tougher than a match,” what I would I say I found out is that ”training is different to a match.”

I’ve already presented some compelling data that the Tennis KPIs that count most (and therefore explain most of the variance in elite tennis performance between those in the Top 100 and those outside it) largely comes down to serve and return metrics. So some of the findings of my research did surprise me somewhat.

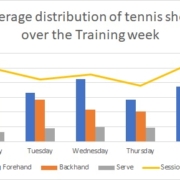

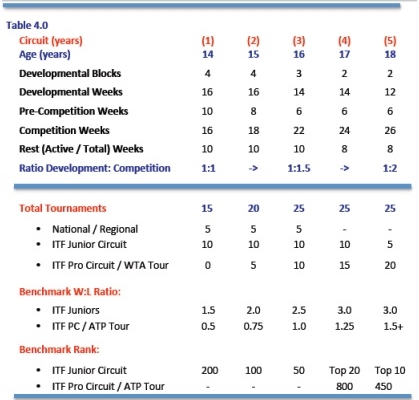

Figure 1 shows the average distribution of forehands, backhands and serves hit during each of the five tennis sessions for the group of Junior full-time players.

On average, the duration of a tennis session was 77.0 minutes in which players hit 190 forehands, 117 backhands, and 43 serves. The average weekly number of forehand shots was significantly higher than that of backhand shots. Both average weekly number of forehand and backhand shots were both significantly higher than that of serves.

On average, the peak stroke rate was 6.8 strokes/minute.

The Serve

In a typical match you can expect to hit around 120 serves, which accounts for 36% of all shots hit in a match.

The biggest finding was that in all juniors tracked, the serve accounted on average for:

8.7% of all shots hit per week, and an average of 43 per day (with a peak of 79).

Groundstrokes

In a typical match you might hit 210 groundstrokes which accounts for 64% of all shots hit in a match.

In my analysis of junior elite players the number of groundstrokes played per session was 278 on average.

Shots in the 0-4 range

In a match, 70% of points that pro male players play are in the 0-4 shot range. For pro female players that number is 66%.

In my analysis of junior elite players the number of rallies played in the 0-4 range averaged 62%.

Or in other words, the majority of points that pro players play, finish before the 5th shot. And that’s worth noting. If pro players’ rallies are ending in the first 4 shots, in practice that means that they are hitting a serve, a return, the server hits a second shot and the returner hits a second shot and that’s it – rally over.

In my research, I found out that the majority of the rallies were in the 0-4 shot range so one can conclude that the training is ”representative” of what goes on it a match. However, one significant conclusion we can make, is that due to the low number of serves hit, it is fair to assume most of these rally exchanges were initiated with some form of feed (either by the coach or one of the players, rather than a serve).

When we focus on what shots the players are actually hitting in matches, I think there’s probably some insight that needs to be taken into account. Like, for example, that the serve and return are pretty important. And I would say that they are really important no matter the level of play. And therefore there is something to be learned from looking at the stats of professional players in matches.

Discussion

The main finding is that there is a large disparity between the average numbers of serves, forehands and backhands hit in each session. The average forehand/backhand ratio in my pilot study was 1.62 which is higher than 1.24 ± 0.37 found for professional male players in competition (Reid et al, 2016). If the overemphasis on forehand shots seems to be a feature of the modern game, it should not be to the detriment of the improvement of backhand shots. Indeed, a study revealed that forehands are associated with a greater number of points won, while more points are lost with backhands played as the final shot (Cam et al., 2013).

It could be argued that these results are unsurprising if one shot is played (or practiced) more than the other. Moreover, the average external load of training seems not to match the demands of competition which may be the goal in the pre-season. The hitting intensities (strokes/min) of groundstroke shots peaked at 6.8 and are lower than those observed by Murphy et al. (2016) for training session (7 ± 1.0), simulated match play (10 ± 5.1) and tournament (14 ± 3.6). This difference could be due to longer rest time and/or a more technical/tactical focus.

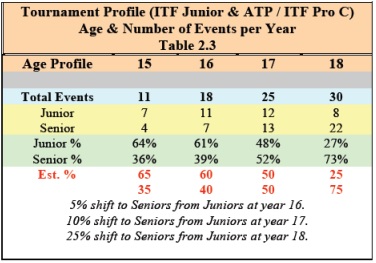

Regarding the average number of serves reported in my pilot study of 43, this number was lower than the 120 serves proposed by Myers et al. (2016). My results are similar to those of Perry et al. (2018) who observed that the number of serves during training session was significantly lower than that of competition for U15 male players (38.6 ± 24.2 vs 82.0 ± 24.8). Because tournament schedules for junior players are often condensed, the players may be required to play several matches in few days with a number of total serves that exceeds that of their current training week. This difference in volume of serves in competition compared to training suggests that coaches should better plan training serve loads (volume and intensity) to match competition to ensure a reduction in injury risk from inadequate exposure.

Coach Perspective

When you are a coach of either one player or perhaps a group of players, you only have 60-90 minutes to develop their game. Speaking to a Head coach recently he shared with me ”When you think how much time it takes to hit let’s say 10 purposeful serves, and 10 purposeful forehands it’s like worlds apart. If you do one serve every 30 seconds that’s 5 minutes, but you could hit those same purposeful forehands in 15 seconds. So that might skew your numbers slightly, and if we were to look it in more detail, we’d have to look at it and say, right, what are we saying a serve is worth versus a groundstroke? I think that’s where I’m at with it.

So player education would be key and one way to improve serving across the week is to say to the kids, you can serve on your own and you need to serve at full power. Some kids will do it, some kids won’t. Also, some re-education of the parents. Unfortunately if I did an hour of serving with a player and a parent was watching, it can look like a slow paced low intensity session, which is a tricky one.”

Training Recommendations

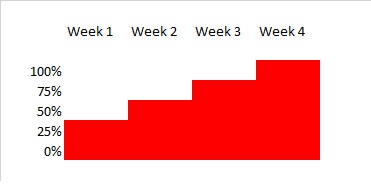

Different recommendations may be implemented during training sessions to both improve serving efficiency and decrease the risk of overload shoulder injury. Firstly, the volume and the intensity of serves should be variable from session to session to allow tissue regeneration and should be planned with intervals simulating the real game (Myers et al, 2016).

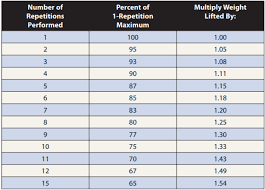

I’d like to see some days where the emphasis is on volume and hitting over 100 serves in a practice, and other days where the emphasis is on intensity, and aiming to hit your fastest serve possible with only 10-20 serves total.

I’d also like to see realistic practice conditions where more of the serving performed is to a returner who returns the ball and then the server has to hit the next shot (serve +1). So many serves I saw were hit into the service box without an opponent, and even if there was an opponent and they did return it, often times the server would not recover their position and attempt to hit it back.

Finally, bear in mind that in a match you may hit over 100 serves and ALL of these are hit with maximum effort. Of the 43 serves on average that were hit in practice, I can bear witness that less than half of those were anywhere close to maximum effort.

Insights from Spellman Performance

Les Spellman, owner of Spellman Performance recently spoke on the Pacey Performance Podcast on the topic of year round sprint speed development. Although the topic was different, if you replace [sprint] with the word [serve] I think the advice is still equally relevant. See below what Les had to say:

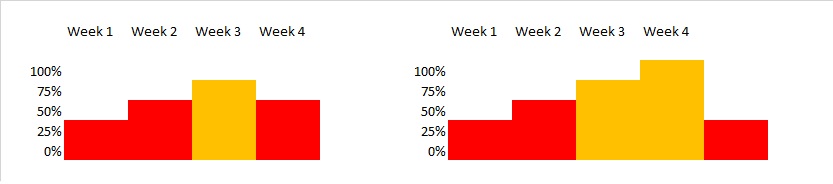

”In-season our approach was to maintain the resisted sprints and you surf the curve (so you go from heavy, to medium and light at different time periods) and then you allow practice to be fast. You allow practice to have the high velocities and you make sure guys hit top speed in games. What we realised was that we are getting the peak outputs in games, which is what you want – you want to play fast.

We are creating an environment where players are allowed to play fast where they’re not coming into the game where they are cooked. Most coaches may think, you don’t want to do those resisted sprints in season as it might pull back from their velocity qualities, but we’re micro-dosing it, we are only doing 2-4 reps in a session. But just that minimal dosage was allowing that athlete to maintain that ability to be very aggressive with their acceleration and have a lot of power, and then practices started to be performed faster, and hit new PBs in speed. It became a culture where guys wanted to run fast in practice.

The game and the actual system should allow players to run fast in practice. It shouldn’t just be a volume base. There should be adequate rest periods. There should be spacing to make the field big enough, wide enough, whatever, reduce the number of players, to allow the players to hit top speed. So you start to get those outputs in game and you don’t always have to artificially expose players to top speed. Now you can if they don’t in practice, okay go and do it. But if you get 95% of top speed reached in practice, okay cool, box checked. And when you have coaches that buy in, and say yes, let’s practice fast, it makes it easy.”

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM