How Do We Learn To Move – Part 2

This blog has been simmering for a few years now. I wanted to share my experiences as someone who has been coaching for 20 years, and has subscribed to one particular philosophy of coaching athletes how to move- only to move away from this way in recent years.

In Part 1 – I summarised an excellent presentation from Paul Venner – Frans Bosch System & Aquabags

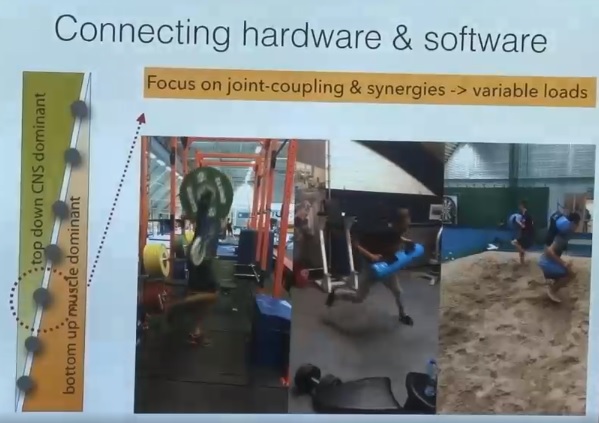

Paul really connected a few dots for me in terms of the synergy between the ”Top down” (CNS dominant) approach and the ”Bottom Up” (Muscle dominant approach). It made me realise why strength & conditioning coaches (myself included) have got a bit lost when we try to ”teach” dynamic movement activities (that have a time constraint) using the same approach we use with the heavy strength compound lifts (that have a load constraint) but where you can take much longer – relatively speaking – to complete the action.

I personally prefer Gray Cook’s explanation of hardware vs software which I referred to in a recent blog – How Do You Decide on the Goals of an S&C programme? Gray Cooks asks:

”Is it a ”software issue”, meaning they just need to practice the movement more to gain competence and develop the software (the neural input- ability to time and coordinate a specific pattern)? Or is it that they lack the hardware (the muscles, the bones, and the tissues resulting from not having enough mobility & stability to get into the position in the first place).

It takes a lot of time for the tissue to remodel. And when you’re doing strength training for the first time you’re doing software re-organisation for the first 3-4 weeks before you ever get any change in tissues like increased bone density or hypertrophy of muscles.”

However, I get where Paul is coming from when he talks about CNS vs Muscle dominant control. He is talking about those motor control process where we have time (think Max Strength) vs those where we don’t (think evading an opponent in rugby).

Power Training Methods

The only word of caution I would give is do your own needs analysis of your sport. There has been an increasing focus on the concept of muscle slack and co-contractions and its importance in high-intensity high-speed actions such as sprinting, jump take-offs and high-speed change of directions.

In practice this will mean focus on maximum power methods which emphasise pre-tension – with little or no external load (in max strength training the load builds tension, but out on the field I don’t have external load so I have to build it myself). This is based on the concept of muscle slack, and getting rid of it! I want to be able to get up without going down first and the way to train that is with pre-tension and using no load or changing loads such as aqua bags to train this ”co-contraction” control.

In my sport of tennis I can find scenarios where this might be the case (running forehand) when they have to run the entire width of the baseline (8 metres) and reach speeds of 4 m/s or more. In this example, all the peak ground reaction forces (GRF) during landing occur within 0.05 seconds (approx 3 x body weight). So yes, some work on power methods that focus on co-contraction could make sense there.

But in a typical 180 degree cut the peak GRFs during the penultimate step take place around 0.35-0.44 seconds – Mechanical Determinants of Faster Change of Direction Speed Performance in Male Athletes (2017).

The 180◦ COD plant step in another study was found to be >0.25 s, the only COD manoeuvre where the plant step was not reliant on a fast stretch-shortening cycle – Effect of Approach Distance and Change of Direction Angles Upon Step and Joint Kinematics, Peak Muscle Activation, and Change of Direction Performance (2020)

So, I would argue that this is a movement where you will use the ”Slow SSC” to go down first in order to get back up, which I refer to as ”load and explode.”

But, any way, back to the topic at hand – How We Learn to Move.

Rob Gray – Software Re-Organisation

Going back to Gray Cook’s point that when you’re doing strength training (or any new skill for that matter) for the first time, you’re doing software re-organisation for the first 3-4 weeks before you ever get any change in tissues like increased bone density or hypertrophy of muscles.

I really like the term ”software re-organisation,” and I think most coaches will agree with the idea that we are trying to get the athlete to organise their movements better – that is to say the ability to time and coordinate a specific pattern, when we are teaching movement skills.

However, in his book Rob offers a compelling argument for why we need to completely review how we have traditionally gone about teaching athletes movement skills. I have highlighted so many passages that really the best thing to do is just go out and buy a copy yourself. In my blog I focus on the first six chapters which cover the theory – the ”Why.” If you want to learn more about the ”How” you’ll have to read the book for yourself.

For those of you who want the ”cliff notes” I’ll try my best to succinctly summarise the key take home points.

Ben Linder – ITF Academy (previously iCoach)

I have to mention first, long before I read this book, it was the work of the Swiss Tennis Federation Head of S&C Beni Linder, that opened my eyes to ”how” to do this practically. He did very little in the way of closed drills.

“Every-time you show a child how to do something, you take away their ability to learn it.”

Our coaching practice should be based on guided discovery, loose description, make the players work it out.” There was definitely an increase in complexity of the challenges throughout the session but even at the beginning when he was working on first step lateral speed to the left or right, he would make it random, and they had to respond to the information in the environment (in this case a command from the coach). There were very few times when there wasn’t some kind of ball (tennis ball or basket ball) that the athlete had to organise themselves with. Check out some of his work on the ITF Academy website if you want more insights on how to use a constraints led approach and differential learning. Any way, back to the book…

Preface

- Soccer, football, baseball and tennis are incredibly exciting, dynamic activities. So, why then do we practice them in such a static, isolated, and choreographed way?

- The dominant view has been that we become skillful by trying to repeat the one, ”correct” technique.

- Repetition is not only not the key to becoming skillful – it is impossible.

- When we acquire a new skill, we want to harness the natural inconsistency and variability in our bodies rather than treating it as noise and attempting to tame it through repetition.

- There is a new role for the coach too. Coaches need to be innovative practice designers adopting approaches like the Constraints Led Approach and Differential Learning.

The Myth of One ”Correct” Repeatable Technique

- Nikolai Bernstein blacksmith study – the experienced blacksmith hit the same spot on the chisel but not by repeating the same movement every time. We repeat an ACTION OUTCOME but not by repeating the movement that produced it – repetition without repetition.

- We don’t repeat our movements, but they are not completely random and variable either. They are shaped by the constraints of our environment.

- Most of the modern history of movement science has been the study of groups. The fact that we can put one number (an average) on an expert’s movements does not mean that there is one correct technique, and all experts do the same thing.

- Variability, not repeatability or repetition, rules the day in skilled performance.

- Having more than one solution to achieve the same outcome makes us robust and adaptable.

The Business of Producing Movements & Why We Don’t Need a Boss

- If the variability in our body allows us to move in multiple different ways to achieve the same goal, how then do we chose which way to move?

- This problem has been coined the ”degrees of freedom” problem. This is to say, in a movement of a joint, you are ”free” to chose the values they have in order to execute an action.

- To understand how we solve this fundamental problem of coordination, let’s look at the ”business” of motor control

- THEORY 1 – control of action is based on a company structure of top down, hierarchical, top-down control. Learning to move successfully primarily comes from having an effective boss (the brain of the company): one that can take in and process all the information and anticipate what needs to be done next. Richard Schmidt – Generalised Motor Programme (GMP).

- We have smartly designed a business that can be broken into parts, trained and then put back together. Examples include: hitting a ball off a tee in baseball or dribbling a ball around cones in soccer. There are no decisions involved.

- THEORY 2 – Self-Organisation. There is no boss! Consider a flock of birds. Individually, their reaction time was about 40 ms. Yet their time to start a turn in a flock was only about 15 ms. When flocking they were turning faster than they could react. In this business model, order and structure in the company arises from the interactions between the lower-level components of the system, not by some rules or a plan given by a higher level. The workers are organising themselves using only the information available to them, without the need for a boss. Instead of a hierarchical system we have perception-action coupling. That is, our actions are directly controlled by what we perceive (without any need for processing and analysis).

Freedom Through Constraints

- Actions are not caused by constraints. Rather, constraints serve to exclude some actions

- So the performer still comes up with their own movement solution through self-organisation – it’s just that their potential options for doing this have been reduced or constrained.

The Laws of Attraction – Part 1

- Why do all elite athletes seem to use somewhat similar techniques for performing things? If skill really involved this highly variable process of self-organisation, shouldn’t we see more variety in the way we act?

- As it turns out, the ”landscape” of perceptual-motor solutions is not flat. Instead it has a few valleys in it, and there are certain relationships that are more ”attractive” and stable than others.

- Even though, in theory, there are an endless number of movement solutions we could use, we all have certain coordination tendencies.

- Why do these attractors in coordination exist? They make us resistant to perturbations. They help prevent injuries. They allow us to deal with the extreme time pressures involved in many sporting actions.

- In order to learn a new skill, in most cases, we need to get out there and explore the perceptual-motor landscape to find new coordination solutions.

- Our attractors will resist our attempts to move into less stable regions of the landscape (even if long term it is a more efficient way of performing the action).

The Laws of Attraction – Part 2

- The athletes we work with are not blank slates. A movement solution is built on top of the perceptual-motor landscape the athlete brings to the first day of practice.

- Some attractors have already been built through early experience.

- The movement solution we come up with is shaped by the constraints we face when practising a skill.

- Effective coaching involves making sure that the constraints that the athlete faces in practice encourage them to climb out of attractor valleys and explore the perceptual-motor landscape.

- How do you encourage a learner to get out of their attractor valleys and get into these unstable regions? By adding a constraint.

- Learning is not a predictable process where we can just give the individual the ”correct technique” and expect success.

- To best support skill acquisition, we need to change the concept of the coach from ”instructor” (I have the correct solution and I’m here to give it to you) to that of a designer and a guide.

- An effective coach should attempt to design practice environments that foster and promote self-organisation rather than prescribing a solution to the athlete.

- The second part of being an effective coach is about being an informed and knowledgeable guide through the search process.

- A common misconception about this new approach to skill, is that it is just ”set it and forget it.’ That is, once the coach designs the practice, they just let it run without saying anything or stepping in. Just let me play games, and don’t coach them how to do it. That could not be further from the truth.

- Coaches should be observing practice to look out for solutions the athlete uses that will not be effective or will have the potential to produce injury. They should also be looking to see if the athlete is not taking the opportunities for action (the ”affordances” they are trying to amplify) they have created.

- In all these cases, the coach can and should step in and try to guide the search in a different direction.

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM