Giving Feedback- Why Less is More- Part 2

In this second part to my blog series on Feedback we are still looking at the feedback from the coach known as external feedback. Here we get into the detail a little more and look at what to say and perhaps also what NOT to say!

For an excellent review of the literature on feedback check out Mattspoint latest blogs on the topic. Part 1 and Part 2. Below are some extracts from Part 2 where he talks about Feedback Timing and feedback Frequency.

Feedback Timing

Overall, coaches and researchers caution against the over-reliance of concurrent -meaning during the skill- (and constant) feedback as it often turns into ‘white noise’, not benefiting the athlete in any meaningful way. From a player and parents perspective, this may sometimes be a challenge – “the coach doesn’t say much”. Truth is, the coach is likely purposely holding back their feedback, allowing the player to ‘figure it out’ before attempting to intervene.

Now of course there’s a difference between an absent-minded coach, one that just isn’t in tune with what’s going on, and one that’s withholding feedback for the player’s sake. But those of you reading this post are likely part of the latter, rather than the former.

Key point – wait until you see a consistent error before jumping in and correcting! Don’t create athletes that can’t operate without your feedback. Allow them space to develop their problem solving ability – this actually builds confidence.”

Feedback Frequency

Interestingly enough, research has indicated that when athletes are given the choice, they prefer to receive feedback about 30% of the time. In many tennis settings, however, the reverse (or worse) is true – coaches are giving feedback 70% of the time or more!

It does depend on the athlete you’re working with and where your skills as a coach lie. Younger coaches tend to say a lot to prove that ‘they know what they’re talking about’. Experienced coaches have ‘been there and done that’ and don’t need that validation.

For instance, ever seen a practice session with two pro players and an experienced coach? Very little is said during the actual session. When I work alongside elite coaches, we purposely set objectives before practice, provide minor cues during breaks/changeovers and a more in-depth debrief at the end of a session. This is even more true as we approach competition periods – I should reiterate, players need space to problem solve on their terms.

Faded Feedback

With faded feedback, a coach will initially provide feedback on every (or almost every) attempt. Research suggests that this helps accelerate the learner’s path towards the movement goal. As the movement becomes more proficient, feedback is provided less frequently – in effect, fading out. The ultimate goal being that the learner can achieve the intended movement without a dependence on the coach and/or the feedback.

The beauty here is that feedback can also be faded back in – in case the movement has regressed in some way. Once it’s back on track, the feedback again is withdrawn.

Bandwidth Feedback

With this form of feedback, a preset ‘degree of acceptability’ is established – with no feedback given when performance falls within the bandwidth and feedback given when it falls outside of the band of acceptability. The key here is that the learner is aware, before the fact, that if nothing is said, the movement is basically ‘correct’.

Research (Sherwood 1988) found that when the band was larger (~10%) compared to the target goal, it was more effective than smaller bands (1-5%). The theory being that less feedback (because of a larger bandwidth) will produce stable and consistent actions over time.

Summary Feedback

Here, feedback is given after a series of attempts – like 5 or 10, for instance. Interestingly enough, this feedback type has been shown to be more effective than trial-to-trial feedback – even though mistakes can be higher during practice, with this approach.

Interestingly enough, researchers found that getting feedback after every attempt promoted too much dependence. At the same time, feedback that was too infrequent (say, after 100 trials), didn’t guide the learner efficiently enough. Based on several experiments, feedback post about 5 trials seems to be most optimal when it comes to longer-term learning.

Tip: If you’re basket-feeding, try for multiple series of about 5 attempts, before intervening with feedback (even if you detect an error beforehand). This approach might have several benefits – first, the player has freedom to self-correct. Second, 5 attempts is still relatively low, so they won’t ingrain a bad habit. And lastly, from a physical standpoint it’s more specific to the demands of actual tennis-play (i.e. work:rest ratios).

Learner-Determined Feedback

This is pretty self-explanatory – feedback is only given when the learner requests it. I’ve encountered this on many occasions when working with elite players. But is it effective?

According to a throwing task study, participants that self-directed feedback, had better throwing accuracies compared to a group that was given faded feedback (feedback frequencies and types were matched). How can this be? Wulf and others in this field of study found that when feedback is learner-determined, it tends to be requested more following successful/correct attempts, compared to poor ones. Isn’t that interesting?

[Daz comment] As a coach I have to say I still feel like I need to be saying things more often and giving feedback and tips to correct their errors as soon as I see them. It’s partly because I feel parents expect it and it’s partly because I am in the habit of wanting to correct an error as soon as I see one- rather than giving them a few reps to figure it out! Wait until you see a consistent error before jumping in and correcting!

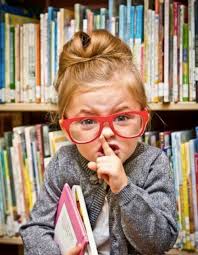

How I feel when I see a technical error- I need to stop myself from wanting to get involved and ‘tell’ them how to solve the problem!

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM