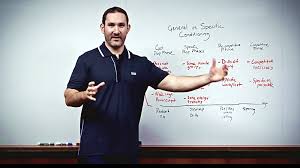

Joel Jamieson: Recovery-Driven Conditioning

Joel Jamieson– online educator who taches coaches how to write science based conditioning programmes that deliver real world results

Related

Ultimate MMA conditioning book

Bioforce HRV

Morpheus

Bioforce conditioning certification

What is Conditioning?

The overall mental and physical preparation in order for someone to compete or perform in whatever environment they are trying to compete or perform in, whether that’s the game of life and you’re trying to stay alive and sustain a healthy life or it’s in the octagon and last from bell to bell for 3-5 minutes.

Conditioning- how well they can use their fitness they have to accomplish something

- Energy system development– VO2max and Anaerobic threshold

- Movement capacity– the energy it takes to perform a movement (efficiency)

- Mental performance– control emotion and heart rate without a massive adrenalin dump

Movement capacity- we try to develop fitness and a lot of times that does mean going to high intensity and causing some fatigue to develop fitness qualities, but what we forget is that as we get fatigued our natural inclination is to let our fatigue fall apart.

If the coach is reinforcing that by saying: ‘Go faster, finish, keep going’ etc the problem becomes that they have learned to have poor technique as soon as they get tired, and have bad habits.

In sport as you fatigue, technique is always what wins! So we have to realise that as we develop these different fitness qualities we can’t let that develop hinder our movement and make us have sloppy technique. That doesn’t haven’t to be the case and it’s a very trainable quality!

Need For A Aerobic Base

Nowadays you will hear coaches say it’s all about interval training now. The research is based on time constraints of 4-6 weeks studies so of course if you are trying to improve fitness in that time, ”intensity is just a driver of the acceleration of things” so if I have 4-6 weeks and testing from point A to point B then training harder is going to lead to better results in those time frames.

But if we look at real world development over 6 months or a year then you can’t just do one intensity all the time. There is something to be said for spending time at lower intensities and higher volume training and greater frequency of training having looked at HRV data for many years.

In most sports that have a high aerobic demand there is a tendency to have a distribution annually of about 80% of time at lower intensities and 20% at higher intensities. That seemed to be a distribution that held true across almost any endurance sport in the world.

First 20-30 seconds of maximum effort work is predominantly anaerobic. After that point you will be predominantly aerobic. Because you were so anaerobic for the first 30 seconds, it takes up until to around 60 seconds of maximum intensity to where the total energy comes around to being around aerobic.

Now of course there is a difference between going for 2 minutes versus 2 hours but both events are going to be predominantly aerobic. It’s more just a question of how the aerobic system is functioning from an aerobic power versus aerobic capacity over the event. If you look at the average speed of a 1-mile and a marathon race the speed is not massively different to go one mile or to go 26. The reason for this is once you get to that 1-mile pace it is entirely aerobic, and when it is entirely aerobic it is possible to sustain that for a long time.

Specificity? Why not just practice the event?

Let’s use the classic indoor Concept 2 Rowing challenge.

A typical interval routine might be: 500m x four intervals with 5 minutes rest between intervals, and over time taper that down to rest to 1-minute between.

But why not just practice my 2000m rowing challenge every session and get better at the race?

It comes back to developing fitness qualities which requires a range of intensities. We are trying to develop different components of the aerobic engine, or anaerobic engine depending on the sport. Those happen at different intensities.

Let’s say I’m training for powerlifting, which is 1 repetition maximum of Bench press, Deadlift and Squat. So why don’t I just come in the gym and max out on 10 heavy singles every session and then walk out the gym? Well most people will say, ”A you’re going to blow your joints apart if you try that and B there is something to be said for doing some higher rep work and some different exercises.”

So we look at strength sports and inherently recognise that we can train for that with higher rep work and different exercises so it’s really the same thing if we are talking about the aerobic engine and aerobic sports. Yes the sport might mean rowing 2k for a few minutes, but that doesn’t mean that only doing that is the ultimate way to develop fitness qualities for it, because there are other intensities which will help us develop the overall biological systems and capacities that we need to get better at that specific event.

So one day a week we try and do a very close to competitive scenario session to get that overall brain-body connection used to that distance and pace and feeling so we do use specificity in training. But again, there are reasons and benefits to using other intensities to build the fitness qualities we need to be able to perform at that event.

Competition

The closer you get to the competitive event the more you want to simulate and recreate as many different parts of the event as possible. That’s where the psychological part of the training comes into play. The brain works by familiarity.

UFC fighters- the guys that have been in the Octagon more times are more calm and don’t get the adrenalin dumps than the person who is going in there for the first time.

There is a reason that the home team wins more than the away time as they are more familiar with the environment.

Train Slow Be Slow

There is no way I’m going on an ergometer for 45 minutes but there is some merit in doing longer work at zone 2 or what we know as that steady zone of 120-150 bpm! So can you just chop up your training into say 10 minutes weights circuit, 20 minutes rowing and then a brisk walk home?

General Central component- adaptations to blood vessel network, and heart are general adaptations that will apply to a lot of different types of exercises. An elite cyclist would still likely do well in other endurance events because they have developed these large central adaptations of aerobic fitness that will transfer to other aerobic events.

Specific component- more specific endurance to the sport, specific motion in leg drive in the exact movement of the bike.

The only caveat with doing general training is that you can’t take this idea that heart rate is equivalent no matter what you are doing. A strength circuit will cause a high heart rate but the resistance of strength training is significantly different to going out for a jog, or a row. The resistance drives my blood pressure up which causes different changes in the cardiovascular system.

But yes going out for a run, versus a bike versus a run can be used to get the general central adaptations, recognizing that the further out from an event we can prepare the body by doing different movements and events. The closer we get to the specific event

If that was not the case then bodybuilders and powerlifters would be great endurance athletes and they are not!

Charlie Francis popularised the High-Low System and he was talking about 70-80% of his overall work volume for his sprinters were tempo intervals at 70% of their maximum speed. So the vast majority of their overall running volume was done at low speeds, but 20-30% towards the end was done at their high speeds.

Now did that tempo interval work slow them down? No! Clearly not, they are the fastest guys in the world! So there is something to be said for the fact that the body is going to adapt to what you do, so if all you do ALL THE TIME is run slow then your body will get better at running at those speeds if you’re doing that over a period of time.

But the idea that any submaximal work is going to all of a sudden slow you down just doesn’t hold up. Your body is going to adapt to the BIGGER PICTURE of things as long as you provide your body with that high speed or high intensity stimulus it’s not going to slow down.

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM