How to make millions as a pro athlete

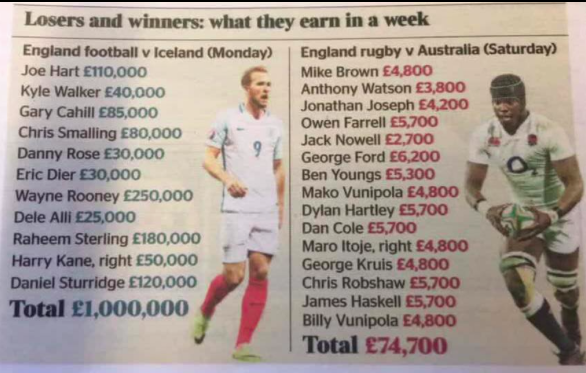

Hopefully that title grabbed your attention. The truth is anything that sells the dream of making millions grabs everyone’s attention. Now some sports are more lucrative than others- for example even at the elite level the very best footballers in the world earn significantly more than the very best rugby players.

And in my sport of Tennis, it is well known that unless you are in the Top 100 you are at best breaking even (not including endorsements). Only once you start getting into Grand Slams can you make a serious living out of the sport- and that’s assuming you can cement your place in the top 100.

Will they make it?

This week I was attending the 2nd Strength & Conditioning in Schools Conference hosted at Oakham School. In his presentation Director of Sport at the school, Iain Simpson asked the audience to give examples of athletes we currently work with that we think have a chance of ‘making it.’ By making it we are talking about earning a living from their chosen sport as a professional. We concluded that no one can give more than a best guess because there are so many unknowns. What we have to do as professionals is give the athlete the best chance of realising their potential without giving any guarantees.

This blog is going to be a quick overview of some key issues that will always keep coming up in conversation and are worth considering if you are faced with trying to answer this question, or are asking it as a parent etc. Here are my Top 5 topics you need to look into:

1. The Birthday Effect:

The age effect is still apparent in certain sports such as football. Those born with ‘early’ birthdays between September and December tend to make up 75% of the footballers who initially get offered contracts with pro Academies. Interesting, at the point of being offered professional contracts the split is 50:50% between the early birthdays and the rest.

Many of the initial standouts flatter to disceive and most are released. But half of the initial late birthdays are offered contracts.

What does this mean?

It means that if you are not born in the first quarter (September-December) you are very unlikely to get selected. BUT….if you do get selected you have a 50:50 chance of making it all the way.

The Director said that this is because one of the ingredients that seems to develop talent is ADVERSITY. The road has to be rocky in order to develop resilience and determination, which are key attributes of those that make it.

2. Environmental factors

There are many roads to Rome: Gold Mine Effect

We are constantly looking for the paths well trodden that have proven to produce talent time and time again. These ‘hot beds’ can be found in different parts of the world. Check out the ‘Gold Mine Effect’ which looks at the environmental impact on talent development.

Check out this cool explanation here

But while as humans we like to feel a degree of security in the knowledge that there is a route to success well trodden there will always be someone that will prove that you can make it going against the conventional way.

Here is a great story of the next star of Ice Hockey who is tipped to be the NHL #1 Draft pick. He grew up in Arizona and didn’t follow the traditional route. Read it here.

3. Deliberate Practice:

Everyone has heard of the 10,000 hour rule. According to Dr Anders Ericsson you need to forget talent: it’s practice that counts.

Read an article here on the subject.

4. Development first: Winning Second

The final piece for me is the role that winning takes in a young athlete’s journey. This is closely linked to the issue of Specialisation.

Click here to read an article on the role of winning.

5. Development first: Specialisation Second

This topic was also touched on in the presentations by Michael Johnston- Senior Strength Scientist for British Athletics, and Andreas Liefeith- Senior Lecturer in Biomechanics at York St John University and Wakefield Wildcats.

It’s a huge topic that deserves its own blog all to itself.

There are no doubt sports that you can say are early specialisation- gymnastics, swimming and I’d even throw in tennis into the mix. These sports require high levels of coordination and relative body strength which can be developed and acquired from a young age.

But with the exceptions of those sports it is generally advised to not specialise in a sport until your late teens. This way you have sufficient time to develop a broad base of motor skills- acquired only by playing a range of sports.

The simple logic is this: is the only tool you have is a hammer, then the only problem you can solve is one that involves a nail

So by learning how to develop more tools in your tool box (more motor patterns-running, jumping, kicking, catching, accelerating, decelerating, balancing, climbing, tumbling etc) you can solve more problems, making you more versatile in solving movement puzzles in the chaos of sport.

For a few interesting articles on the topi read Here and Here