Periodisation for Tennis – Part 4

One of the benefits of running a strength & conditioning coaching company is that each year I get to mentor a new set of coaches. In the last few weeks two questions have been raised by some of the interns which I thought would make a good blog topic for discussion.

- How do you decide on the goals of the S&C programme?

- How do you periodise the goals into an Annual Training plan?

I covered the first question in my last blog – Click here and now I will turn my attention to the second question of Periodisation.

I’ve probably written about this topic as much as any on my blog and usually it’s when I have been trying to figure things out and make myself accountable to commit my thoughts to paper. So certainly there has been some good stuff, and some not so good stuff, some things I still agree with and some things I have changed my mind on.

But for what it is worth – take a look at some previous blog articles – Periodisation for Tennis – Part 1; Periodisation for Tennis – Part 2; Periodisation for Tennis – Part 3; Periodisation for Teenagers; Periodisation – Hybrid Models for team Sports; Periodisation – Does it Even Work?

I also wrote a review of the Triphasic Method – click here and here, which are the probably the two most recent blogs I have written about on the topic of Periodisation.

All of the above blogs talk about frameworks and models but having gone back through them all it was actually the Periodisation for Tennis – Part 1 that I want to talk a little bit more about. In the team meetings with my staff we have been discussing how you go about solving the problem of working in Tennis where the athletes rarely complete several cycles of 4 consecutive weeks.

Junior Elite Tennis Players

Let’s take the example I gave of a female player in the 14-unders (double periodisation) and moving into 16-unders at aged 15 (triple periodisation). For boys the equivalent could be moving out of 16-under and into 18-under.

The STATS

- At 15 yrs they might play 35-75 matches per year

- They may play up to 9 international tournament

- They may play up to 3 consecutive tournaments in a row

- They might have 3 training blocks a year (triple periodisation) up to 8 weeks each

Almost 50% of the top 100 ITF ranked junior

girls fail to plan 1 block of 8 weeks and 1

block of 4 weeks (Raabe & Verbeek, 2004)

More STATS

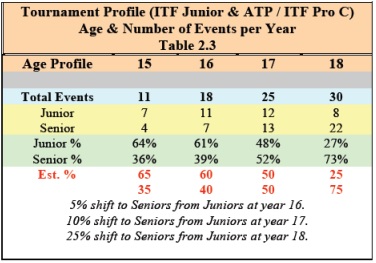

McCraw, P. Making the ATP Top 100. Transition from Top 10 ITF Junior to Top 10 ATP Tour (1996-2005).

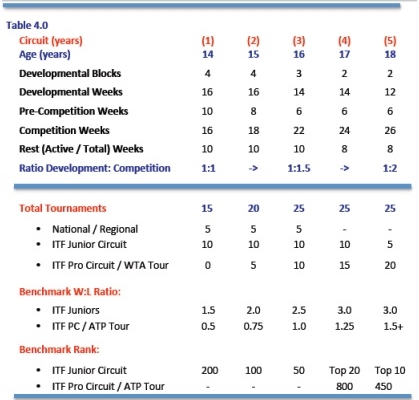

As you can see, different researchers report slightly different stats, but you can gather from the research that children can be playing tournaments from anywhere from 11 to 30 weeks of the year, with 12-16 weeks of training (development weeks) and 8-10 weeks of rest.

In reality, the best outcome is one longer training block of 8 weeks and probably two shorter ones of 4 weeks each, and a lot of 2 weeks in training followed by 2 weeks in competition.

When you have 8 weeks

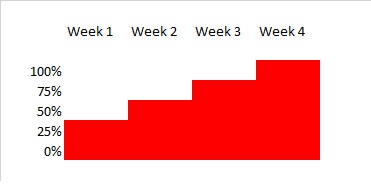

This is what I would do with a less advanced athlete. I’d do a 4-week build up phase, what I call the ‘GET FIT’ PHASE, and I’d follow it with a GET STRONG / GET EXPLOSIVE phase.

Phase 1 – GET FIT (Foundation) – Early Preparation – Hypertrophy

Phase 2 – GET STRONG / GET EXPLOSIVE – Late Preparation – Max Strength and Power

With my more advanced athletes there will be ‘loading’ of all parts of the Force-Velocity curve from the beginning of the preparation period, which will only be 4 weeks in most cases. It will be the emphasis that I will shift BUT all forms of training are present from the outset. This means that advanced athletes will be loading up on hypertrophy, strength and power either in the same session or at least in the same week (microcycle). See later in the blog for more information on this.

But What Happens when they come in for 2 weeks and go on the road for 2 weeks?

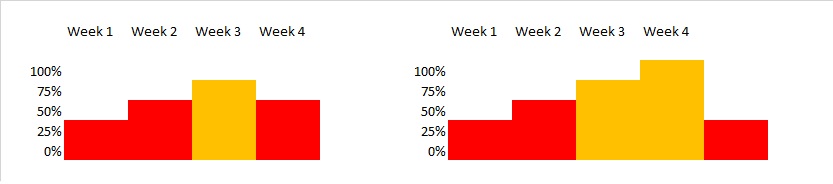

In the above figure (on the left) we have a scenario where the athlete has trained for a few weeks and built up the intensity, only to then go on the road for 1 week. The orange column was supposed to be a 75% week (of the planned 100% of intensity for that block). If they only go away for a week I just get them to repeat the load of the previous week.

If they go away for two weeks in a row (on the right) where they would have achieved the planned 100% load had they stayed for a full month in training, when they come back, I have to start from scratch!

The only way to break this cycle is to lift on the road – preferably as soon as they exit the tournament but before the following week

The key with in-season programming is to have your ‘benchmark’ levels of performance that you can hold your athlete or team accountable to. I want my less advanced athletes to be motivated to keep making progressions in the intensity of their lifts, and buy into the principle of ”no missed lifts.”

For my less advanced athletes I really want to get them to progressively build up to a few cycles of 100% intensity before switching up to a more concurrent method (see below).

As for the more Advanced athletes

A couple of common approaches to strength training in-season are:

1 . A weekly undulating model – An undulating model as proposed by Charles Poliquin uses weekly variations in load. It is quite common as an in-season model which fluctuates between 1-2 weeks of hypertrophy and 1-2 weeks of maximal strength/power. It allows the CNS to recover during periods where there is already high neural stimulus from a busy competition schedule.

I believe Dan Baker uses this form of week to week variation in strength sets and reps schemes to maintain strength and muscle mass using a form of weekly undulations in strength. (Undulating wave 12/8/10/6). In this example the weeks of 12 and 10 reps would represent hypertrophy weeks and the weeks of 8 and 6 reps would represent strength.

2. A daily undulating model– which uses variations in the same week. This is something we use quite a lot with Tennis players where we will plug in a session which combines Strength and Power a couple of times a week. Or you can have one session which focuses on a strength and one which focuses on power. This is an example of the concurrent method – where you are training strength and power in the same week.

In the earlier scenario above, where they miss a few weeks of strength training while they are competing I am less concerned about this. I feel more confident that I can get them back into their training by progressively increasing load during the first week. I can do this by doing a 50% load in the first session back (muscular endurance 3 x 12-15), a 75% load in the second (hypertrophy 4 x 6-10) and by the third session of the week we can be getting back to our 100% load (max strength 5×5). So we top up their strength the first week they are back.

Then in the second week we can do the session which combines Strength and Power a couple of times a week. Or you can have one session which focuses on a strength and one which focuses on power. This gets them feeling a little sharper before they go back on the road again.

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM