How Do You Decide on the Goals of an S&C Programme?

One of the benefits of running a strength & conditioning coaching company is that each year I get to mentor a new set of coaches. In the last few weeks two questions have been raised by some of the interns which I thought would make a good blog topic for discussion.

- How do you decide on the goals of the S&C programme?

- How do you periodise the goals into an Annual Training plan?

Where to Start?

These are fundamental questions all coaches need to ask and a thorough needs analysis is required which boils down to gathering information on:

- The Athlete

- The Sport

- The Training Philosophy of the Organisation

Regardless of which sport you may be focusing on, there are so many outstanding coaches to learn from. I aspire to have a Training System that other practitioners will find helpful and be impactful in our industry. I’m certainly not where I want to be yet, and many of my ideas are influenced by others. The list is too long to mention everyone but the list below is based on coaches I have taken the time to study their methods in detail.

- Baseball – there are some incredibly bright coaches in baseball and I have studied everything I can get hold of from Eric Cressey (Cressey Performance). Also Mike Robertson (Indianapolis Fitness and Sports Training (IFAST) in Indianapolis, Indiana), Randy Sullivan (Florida Baseball Armory)

- Combat sports – Danny Wilson (Boxing Science), Dr Duncan French (UFC)

- Tennis – Matt Kuzdub

- College sports – Cal Dietz

- Training facilities – Mike Boyle (MBSC), Mark Vestegen (EXOS), Joe DeFranco (DeFranco Training)

- Field sports- Dan Baker, Vern Gambetta, Kelvin Giles (Movement Dynamics)

In this blog I’ll focus on the goal setting process and specifically the Athlete. Many of my ideas have been influenced by the coaches above, and others besides. I’ll touch on Periodisation but I’ll go into more detail on that topic in a follow up blog.

The Athlete

When you work with an athlete for the first time, in order to set some goals you need to determine what their strengths and weaknesses are. This starts with an Assessment process. Early in my career in 2003 I was fortunate to read ”Athlete Body in Balance – Gray Cook.”

This is still one of my go to texts that I like to re-read each year. I really like the concept of developing the Athlete through a progressive approach starting with Functional Movement –> then Functional Performance –> and finally Functional Skill.

Functional Movement – Move Well

Off the back of reading Gray’s book and also having the opportunity to learn from Kelvin Giles, I created the APA Physical Competency Assessment (PCA). I describe it as a bridge between a physiotherapy musculo-skeletal screen and a Fitness test. We look at the function/competency of the athlete’s movements in a range of patterns:

- Overhead Squat

- Lunge & return

- Single leg squat (pistol on a box)

- Hop & land

- Press up

- Lying pull up

These movements require a combination of mobility and stability and relative body strength. They show you if an athlete has the competency to perform a movement but they don’t necessarily highlight the reason why an athlete can’t perform them. Is it a ”software issue”, meaning they just need to practice the movement more to gain competence and develop the software (the neural input- ability to time and coordinate a specific pattern)? Or is it that they lack the hardware (the muscles, the bones, and the tissues resulting from not having enough mobility & stability to get into the position in the first place). So this is where the musculoskeletal screen comes in handy as it gives more clues. Some strength & conditioning coaches are more interested in functional anatomy and physical therapy etc and develop expertise in how to assess individual joints for strength and range of motion.

I personally try to up-skill myself on these type of clinical assessments each year but I’d rather refer out to a physiotherapist for the most part. I tend to focus more on looking at gross movements rather than individual joints. However, it definitely pays off to understand Functional Anatomy better.

As Gray Cook says; ”it takes a lot of time for the tissue to remodel. And when you’re doing strength training for the first time you’re doing software re-organisation for the first 3-4 weeks before you ever get any change in tissues like increased bone density or hypertrophy of muscles.”

That’s because most of us can organise a movement situation well if we are moving well and we do it often enough to allow for healthy adaptation – your first adaptation is going to be neural and your second adaptation is tissue.

Yet much of our fitness is focused on tissue. Now you may be able to re-set and or reprogramme the neural software in a matter of minutes and get changes within a session. In terms of tissue re-modelling it takes weeks and months to make those kind of changes, which is why I guess it becomes a focus.

Elite Adult

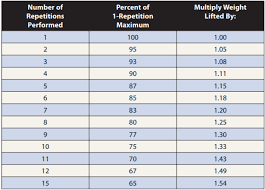

For an elite adult I broadly talk about it taking 12 weeks to Peak (that’s based on 4-6 weeks strength block*, 2-4 weeks power block and 1-2 weeks speed (peaking) block). But the strength block is a maximum strength block meaning loads above 85% 1RM from the get go.

For a great example of how a collegiate level athlete might go about this I highly recommend you read Triphasic training by Cal Dietz – or you can read by blog overviews here and here.

Clearly this type of training approach is only appropriate to someone who has training experience and is quite ‘Advanced.’ So a novice adult undertaking a training programme for the first time would need to build up to lifting those kind of loads and would do more ‘basic’ training to prepare for that, which might take another 12 weeks of progressive loading of the tissues.

Below is an example of a 6 month training plan – assuming no interruptions in training, all phases are 4 weeks and separated by a week of unloading.

- Hypertrophy – 3-4 x 8-15 reps – 65-80% 1RM

- Strength – 5 x 5-8 reps – 80-87% 1RM

- Maximal strength – 5 x 3 reps – near maximum force – 93% 1RM

- Maximal strength* – 5 x 1-3 reps – maximum force – 93-100% 1RM

- Explosive power – 5 x 3-5 reps – 50-80% 1RM

- Speed – 30-50% 1RM

There is an argument that unless you are in the professional sport of power lifting or Olympic weight lifting you may not need to go to maximum force loads due to the extra stress on the body, but I’ll address that when we talk about the demands of the Sport in the next blog. It’s also not possible in some sports to have athletes commit to 12-24 weeks in a row without some form of competition, so again I’ll address that in the next blog.

I have regularly used this systematic approach in my own training to fully appreciate how my body feels during each training phase. I have also used it with adult clients who can commit to seeing me consistently.

Key point: During the first phase, which is associated with lower intensity work, often called Hypertrophy phase, it is a good opportunity to work on the hardware and software to improve how well the athlete moves. At APA we refer to this as the GET FIT phase. It’s probably not the best term to describe it, as GET FIT probably makes coaches think of lots of continuous runs and bodyweight circuits. Although the aerobic fitness is part of it, it is about laying a foundation of fitness that ultimately sets the body up for success in the next phase.

The GET FIT phase would be an ideal time to use the PCA to assess your athlete to see how well they move.

Functional Performance – Move Fast

Needless to say that strength and power work in the gym are critical components of the training we use to develop the ultimate goal of moving fast – producing high forces at high speeds. There are slightly different assessments we can use to assess the athlete here.

Now I’m not going to go into specific details on the Fitness test and some of the other strength/power tests that you can use as part of the ”Functional Performance,” aspect of assessment. These are broadly speaking well understood by coaches and are used to see how much horse power the athlete is capable of harnessing. This is where you can use:

- Sprint tests – to measure acceleration and maximum velocity

- Jump tests – to measure power output

- Endurance tests – to measure aerobic speed and anaerobic power/fatigue index

- Strength tests – to measure peak force and rate of force development

At APA I personally start to incorporate all these tests with secondary school age children onward (11 years and over) to build up a picture of an athlete’s strengths and weaknesses. Even though there is a typical hierarchy to the way we progressively remodel tissue (progressive overload) – of volume to intensity (endurance to speed) it is still useful to know which aspect the athlete is better or worse at to best target the training most effectively. Some athletes are better at sprint and jump tests, but find endurance and strength tests more difficult. Others, for example, are very strong in the gym but struggle to express that force at the time frames required in sport (so will need more speed and power work). You get some athletes that are outstanding in endurance activities, some who are generally good across the board, and also others who are generally poor in all areas.

Key point: During the second phase, which is associated with higher intensity work, often called Strength phase, it is a good opportunity to work on upgrading the hardware to improve how fast the athlete moves. At APA we refer to this as the GET STRONG phase. If an athlete is a beginner or has had a long period off training, we will do the training in a sequential fashion meaning there will be a focus on strength first. Then we change focus to Power which at APA we refer to as a GET EXPLOSIVE phase.

The GET STRONG and GET EXPLOSIVE Phase would be an ideal time to do a Fitness test.

Risk Reward

Please be cautious with what sort of assessment you do here and WHEN in the training plan. All coaches like assessments and numbers and want to benchmark starting levels of functional performance. This way it is easier to show improvements. I get it! But you may be testing a quality that you have not yet trained fully so the idea of asking an athlete to give a maximum effort in a particular test (such as a 20m sprint or a 3RM back squat) may be a risk if it comes at the wrong time.

So please be cautious if opting to do a Fitness test at the beginning of a GET FIT phase.

If I am going to do it at the start of a GET FIT PHASE I usually get children to do the Fitness test after a few weeks of training so not to shock the body in the first week or two of resuming training (even though some coaches will say they are not at a true baseline level of performance a few weeks in, I’d rather not take the risk of getting an injury).

As for strength testing, with technology and some simple maths we can estimate strength and power levels pretty well from sub-maximal loads without needing to go to maximum. APA are fortunate to have a Gym Aware to measure bar velocity so it can help in this regard.

Children versus Adults

Now with children you can’t expect them to reach those levels of tissue loading in 12-24 weeks.

It is generally understood that the body is physically better equipped to handle more intensive training means once children have been through puberty. By this stage they have finished growing and their hardware has been upgraded thanks to the surge in hormones and increases in lean mass. So how do you approach working with children?

Long term Athlete Development

In 2005 I read a really interesting book which really helped me to consolidate my ideas around the APA Training System. The book talked a lot about the Key Stages of Long term Athlete Development (LTAD) and also Optimal Windows of Trainability. The book also gave some really good insights on Periodisation concepts and how much competition per year a child should do as they go through the stages of development. I’ll go into more detail on this in the next blog.

I used the principles of the book to design six stages for my training methodology (At APA we talk about Basic level– 3 stages – which covers childhood and puberty, approximating 10-under, 12-under and 14-under; and Advanced level – 3 stages- which covers post puberty onward; 16-under, 18-under and pro level). Note that for girls, these stages could occur two years earlier. I typically think of post puberty as a jumping off point to ramp up training intensity to the Advanced Method (although I have been known to introduce higher loads in adolescence if the child has a good training history).

I personally give credit also to Jon Oliver & Rhodri Lloyd – The Youth Physical Development Model (2012), which brought into focus the idea that critical windows of training needed updating and actually all training qualities should be trained all the time, and particularly that strength needs to be a focus from middle childhood (5 yrs old) all the way through to adulthood.

Going back to Gray Cook’s point that when you’re doing strength training (or any new skill for that matter) for the first time, you’re doing software re-organisation for the first 3-4 weeks before you ever get any change in tissues like increased bone density or hypertrophy of muscles. When I think about all the skills I would want a complete athlete to have, that gives you a pretty good idea that one of the priorities in childhood is to learn all the Fundamental Movement Skills (FMS) as well as Fundamental Sport Skills (FSS), collectively these are known as Physical Literacy.

If you think about it there are a lot of movement skills to master:

- ABCs (Agility, Balance, Coordination, Speed)

- RJT (Run, Jump, Throw)

- KGBs (Kineasthesia, Gliding, Buoyancy, Striking with objects)

- CPKs (Catching, Passing, Kicking, Striking with body)

When strength is developed alongside FMS it creates a foundation for all other forms of exercise and helps children to develop controlled movements. So the biggest part of assessment of a youth athlete is assessment of Physical Literacy in a range of skills.

Key Point: At APA we refer to these Fundamentals under the umbrella term ‘SKILL.’ Skill has three sub-components:

- Reaction speed

- Balance

- Coordination – I include all the RJT, KGBs and CPKs under coordination

I refer to Agility & Speed under ‘SPEED’ and there are 5 Biomotor Abilities that make up the APA training system.

- SKILL <– Coordination Profile

- SUPPLENESS <– PCA

- SPEED <– Fitness test

- STRENGTH <– Fitness test

- STAMINA <– Fitness test

How Do You Test Skill?

At APA we created the Coordination Profile which is an assessment specifically created to be used with children as it doesn’t bias higher performance to those children who are more physically mature, as you would see with the Fitness test. To be honest, it used to be a very big part of the Training System, but now the challenges have been incorporated into the syllabus rather than performing lots of assessments with the younger children.

The Full version has 14 different challenges and the Modified version has 7 which includes challenges like skipping rope, throwing, balance, racket skills over an obstacle course, hexagon drill, reaction ball and a jump.

Even if you haven’t created a specific assessment to ‘test’ skill, I’m pretty sure that most coaches have developed a progressive training syllabus where the focus of the skill changes throughout the year. James Baker was someone in the 2000s who was a leader in bringing more ‘physical’ into the Physical Education syllabus at his school – St Peters High School- between 2013-2017 before moving to Qatar to work at Aspire. You are only limited by your imagination.

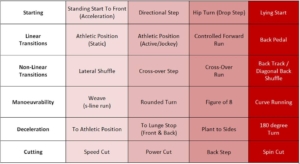

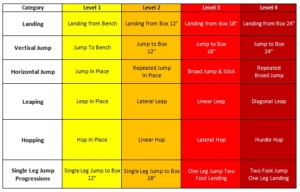

Below are some simple example progressions of skills for speed and strength that could be used to informally assess and teach a youth athlete. Essentially our annual plan takes into account all the software organisation (uploading) we want to do, so by the end of the year we have more skillful athletes – who MOVE WELL.

Hope you have found this article useful. I’ve included lots of different links to coaches that have influenced my ideas about athlete assessment. It should give you plenty of places to look for further ideas on all the different types of assessments you can do.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM