Should we be doing core stability training?

I have just come back from my second workshop with Biomechanics Education, ‘Spine Biomechanics.’

This workshop focused on core stability which is an area I was more familiar with than the previous workshop on Pelvis Biomechanics. One of the key questions that raised my interest was,

Should we be doing core stability?

It’s a good question. But before we can answer that question we need to first ask, ”what exactly is core stability?” Do a web search for core stability and you get 13,000,000 results.

Definition of Core Stability #1

Search for a definition on Wikipedia and you get, ”Core stability relates to the bodily region bounded by the abdominal wall, the pelvis, the lower back and the diaphragm , spinal extensor muscle and its ability to stabilise the body during movement. The main muscles involved include the transversus abdominis, the internal and external obliques, the quadratus lumborum and the diaphragm, erector spinae and multifidus lumbar.

It is the action of these muscles contracting together upon the incompressible contents of the abdominal cavity (i.e. the internal organs or visera) that provides support to the spine and pelvis during movement.

Definition of Core Stability #2

Muscles stabilising or supporting a body segment statically or dynamicall while other muscles carry out a movement involving other joints (Siff, 2004)

What might you see on the Internet?

Type in core stability in Youtube and you’ll see thousands of various sequences posted by Personal trainers and S&C coaches. I too have done it, but I’m now looking to be more targeted with my prescriptions to my clients. Not all clients need and will benefit from being given the same exercise prescription. I have always known about the progressions from stable to unstable and unloaded to loaded and static to dynamic etc but today I have developed my thinking further and I am better able to see how I can develop the base of the pyramid by integrating the Biomechanics Education Model into the Suppleness section of the APA Training System.

A note on Rectus Abdominus

Traditionally we focus on the role of rectus abdominus as a spinal flexor. But actually its main purpose is to create tension to stabilise the spine when performing tasks that require spinal stabilisation. This is due to the fact that the Tranversus Abdominus (TA) inserts into the Rectus Abdominus.

This type of training for the Rectus Abdominus became known as ‘Anti-Extension’ training and from that sporn other exercise series with the same aim- to resist the shear forces that act on the spine during dynamic motion:

Anti-extension: Full Kneeling Band Anti-Extension Overhead

- Anti-extension

- Anti-flexion

- Anti-lateral flexion

- Anti-rotation

Anti extension: Ab wheel: roll-out

There are a lot of exercises which have spun off this concept, the most popular ones being:

- Planks

- Pallof press

- TRX fallout

Anti-extension: TRX fallout

Myths- Hollowing versus Bracing

I’ve been involved in the health & fitness industry since 1998. Prior to the latest buzz of anti-extension exercises when I was first involved in it core stability was all about hollowing. I even bought a pressure biofeedback unit so I could see if the client was doing it well.

The rational was that TA and Multifidus were most active during hollowing- the muscles once considered as the most important muscles in the core. But as we discussed today with Rachel at Biomechanics Education, if only one group or muscle of the full range of stability muscles is not functioning correctly, then the trunk is unstable. (Chollwewicki and McGill, 1996, O’Sullivan et al, 1997, 1998, Allison et al, 1998).

So now the focus is on ‘bracing.’

During daily life, 10-25% of Maximum Voluntary Contraction (MVC) is often enough to stabilise the spine. In the exercises which we discussed for core stability we might start at that level of contraction but the effort could go up as we progress through the exercises.

What about holding your breath?

Something I learnt today is that it is generally advisable to practice both holding your breath AND not holding your breath in training during core stability exercises.

I had always been taught- I say taught- I mean informed through the videos I had seen- that you are only effective at stabilising your core if you can maintain the bracing without holding your breath, so it was refreshing to hear you can practice both. And what’s more it is entirely appropriate to hold your breath when training at higher intensities (Cholewicki, 1996).

What about Sit ups?

Sit ups and crunches- here’s the thing. everyone- even the man off the street who has never set foot in a gym will be able to tell you that the best way to get a six pack is to do crunches- right?

In the 1980s all everyone was doing was crunches- in the 1990s and early 2000s it was hollowing- mid 2000s it has been anti-extension exercises. This loss in interest in crunches and sit ups- at least in the sports conditioning community- was in part influenced by research from McGill and the like who demonstrated that the compressive loads on the spine during crunches (~3500N) exceeded its safe amount of load of around 2400N.

It was then shown that there were even more compressive loads on back extensions (greater than 4000N) on a Glute Ham raise and even more when doing them on the floor when you lift up both the legs and the arms (~6000N)

Back extension on Floor

[Author’s Note: the following is my opinion and not the opinion specifically expressed or discussed by Biomechanics Education]

I personally feel that there is always going to be a risk:reward equation to factor in when making any decision on the most appropriate exercise prescription. But when someone is playing sport or has a physical job that DEMANDS these type of compressive forces then you have to be conditioned for them.

Am I saying do 300 crunches every night to get a six pack?? Of course not- besides that alone wouldn’t achieve that goal it even if it didn’t put a lot of compressive force on the spine. But that’s for another blog.

But I am saying that if you play sport you might want to consider adding them in to your programme at some point because spinal flexion, side flexion, extension and rotation all happen in sport.

So going back to the question I asked at the beginning, should we be doing core stability?

Here’s the case for Yes….

There is clearly quite a strong theoretical basis for doing core training. It is commonly believed that core stability is essential for the maintenance of an upright posture and especially for movements and lifts that require extra effort such as lifting a heavy weight from the ground to a table. Without core stability the lower back is not supported from inside and can be injured by strain caused by the exercise. It is also believed that insufficient core stability can result in lower back pain and lower limb injuries. Equally core is often inhibited in cases of Lower back pain (LBP). Whether the core weakness caused the LBP or the LBP caused the core weakness is another story!!!!

But…..here’s the case for No

There is little support in research for the core stability model and many of the benefits attributed to this method of exercise have not been demonstrated. At best core stability training has the same benefits as general, non-specific exercise.

- Kriese M, et al Segmental stabilization in low back pain: a systematic review. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2010 Mar;24(1):17-25. Epub 2010 Mar 16

- Rackwitz B, et al Segmental stabilizing exercises and low back pain. What is the evidence? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2006 Jul;20(7):553-67

- May S, Johnson R. Stabilisation exercises for low back pain: a systematic review. Physiotherapy.2008;94(3):179-189

- Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, et al. Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother 2006;52:79–88

- Macedo LG, Maher CG, Latimer J et al 2009 Motor Control Exercise for Persistent, Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review PHYS THER Vol. 89, No. 1, January, pp. 9-25

- Lederman, E. The myth of core stability. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2009.

But overall my answer is Yes and here is my reason Why.

Biomechanics Education Three Steps to Stability

If just doing ‘Indirect’ core work such as Deadlifts, Squats, Pull ups, press ups etc (which clearly place high demands on the core) was enough then I wouldn’t have some of the issues I have been managing for the last 15 years.

You see I have been managing some low grade discomfort (not LBP) which has caused muscle spasms in my QL, adductors, hip flexors etc over the years. I have concluded I have a rotated pelvis which happened after a over zeolous squat in the smith machine when I was 20. That caused a functional leg length difference and ever since it created some ‘issues’ both above and below my pelvis.

So when I do core work there are usually some form of compensations at work. This has lead to imbalances and as a result if I just did indirect core work I’d be still compensating. Only by determining where the imbalances are and working on them with DIRECT core work can I begin to return my body to normal function.

I’m not going to give all the good stuff away. Rachel wouldn’t be happy but I will say this much. The Biomechanics Education system develops core through three layers.

- Core Stability- bracing exercises

- Muscle ratios

- Functional stability

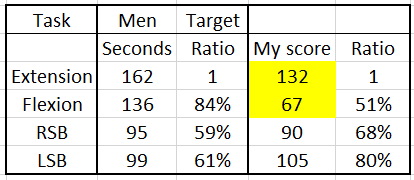

Here’s some basic information on the Muscle ratios for me when I tested it today:

So you can see that there are clearly some imbalances. I didn’t meet the target for spinal extension of 162-seconds, but even more noticable is how far below my time is for spinal flexion. So clearly I CAN make a case for doing more spinal flexion work in my specific case and also a little more emphasis on the Right side bridge (side plank).

Here’s me doing the spinal extension test

For more information head over to Biomechanics Education.

P.s here’s the latest boxing circuit I did this week. Absolutely brutal. About 30-40 minutes all together.

Circuit 1: Upper body

0.5kg dumbbell -100 shadow punches (left jab, right cross)

1.0kg dumbell- 80

2.0kg dumbell- 60

3.0kg dumbbell- 40

4.0kg dumbbell- 20

30/20/10 Tricep dips- with 15-seconds between before moving on to the 2.0 and then 10 reps

25 Medball slams with 4kg Medicine ball.

This circuit was repeated 3 times with 1-minute rest between circuits. Circuit 2 was shadow punches but they were crosses and Circuit 3 was uppercuts.

Circuit 2:

30/20/10

Round 1: all exercises 30 reps

1. Squats

2. Calf raises

3. Split squat jumps

4. Step ups

5. Med ball slams

6. Burpees

After 1-minute rest repeat. Round 2 was 20 reps. Round 3 was 10 reps.

Well that’s enough talk from me for one day! Enjoy your training.

1). As your core is a group of muscles that are recruited during sport, surely training them to increase their strength (if done appropriately) will be of benefit to performance, as with any other muscle?

2). Can you explain how the main role of the RA is as a spine stabiliser? Is the movement RA is responsible for not spinal flexion, and therefore it’s main role? This study found that RA recruitment was <20% EMGmax during abdominal bracing compared to 80% during v-sits (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3772590/).

Hi Jonny. Thanks for the comment. I didn’t manage to publish all the comments in the past as there was a lot of spam and we blocked all comments without review first- and I must have missed yours. As I stated in the blog it’s main role is a stabiliser. This is due to the fact that the Tranversus Abdominus (TA) inserts into the Rectus Abdominus. Your findings of the study doesn’t necessarily challenge the concept of their main role- just because they are more ‘active’ in another exercise. It just means that their primary role is to brace and secondary role is to flex. However, as with many interpretations of scientific data many coaches would then jump on the flexion bus because emg activation is higher.

Core exercises strengthen your abs and other core muscles for better balance and stability.