The Dubious Rise of the Corrective Exercise ”Pseudo-Physio” Posing as a Trainer- My thoughts

This week with pre-season starting for some of my professional Tennis players I have recently being reviewing the training plan I have written and reflecting on how I was going to ensure that all the athletes get what they need. It threw open a few good debates with the wider Performance team about the purpose of fitness testing, and also musculo-skeletal testing. Does it need to be done- was basically the question the sports coaches were asking of me?

I have also been personally reflecting on my own roles as a strength & conditioning coach and reflecting on how much knowledge I need to have about the way my different athlete’s bodies are functioning from both a physiological and anatomical stand point. For years I have seen new coaches pop up posing as corrective exercise specialists and offering in depth movement assessments and postural corrective exercise. How much does my programming in pre-season need to speak to these individual differences?

There’s also a rise in athlete monitoring tools that can basically measure anything you want so again I want to be clear on what I am measuring and why.

Does every athlete above need a completely unique programme?

As controversial and popular topics go these are certainly ones I have followed for a few years now, and at this time of year I like to reflect on this as well.

So this blog is really a response to three topics- the first one is about the value of fitness testing from my perspective. The second one is my views on corrective exercise specialists. The third one is my take on athlete monitoring. I will include two links to two recent articles which I highly recommend you to read.

Fitness testing

So the situation is the week before pre-season and one of the professional players is due to return for pre-season. They have had a week off on holiday at the end of a long competition campaign (in Tennis that basically means around 25 tournaments in 10 months).

The athlete in question has a long history of training, has probably been tested annually for the last 13 years in some form or another and generally knows how they are going to score. He also feeds back that very rarely does he feel that the test results actually determine the training programme. It is usually based around the areas he feels he needs to improve to win more points/lose less points. So the Performance Team made up largely of tennis coaches ask the question, “Do we need to do it?”

Initially I am a bit dumb founded because I am thinking to myself, “Are you serious?” but then I sit back and think it’s actually a smart question that deserves a proper answer. Testing require maximal effort over several tests across various fitness parameters such as strength, speed and stamina- some of which are in tests that are not specific to the movements of the sport. The risk-reward equation plays heavily on the mind of the sports coaches too who are protecting their prized assets from unnecessary risk. I get it. Does the test actually influence the subsequent training? Do we need to ‘sacrifice’ a day before and after a testing session to recover? Do we need to push them in the first few days back?

Yes is my reply! we need to know where they are at! Assess don’t Guess– is my standard retort but……..let’s look at this more deeply:

If you have an athlete with so many years data behind you, are you really guessing? When there is a lay off through injury, or there is a reduction in training for some other reason for more than a few weeks then it is a no brainer. Historically myself and the Head of Sport Science & Medicine I work closely with at the Tennis Academy have said you need to be at above 80% of your baseline markers to return to a full training and competition schedule. When you have a lay off we need to know if you are above 80%.

But if the athlete has years of training history, is fit and healthy and has only had a short vacation to re-charge the batteries this discussion warrants further comment. For the athlete in question I still say test. Even if we suspect through intuition that they will hit these markers I like to test for another reason:

- To determine the effectiveness of the training intervention- pre and post training scores

- To test their competitive spirit

- To create a clarity of purpose with something measurable to beat

Generally speaking assuming the athlete is fit and healthy we may well be able to predict what scores they will get within 5-10%. But crucially, we may not be so easily able to estimate what percentage of improvement we have made in the 4-week pre-season. I like to know rather than just rely on the athlete’s feeling that they are fitter, faster and stronger.

General versus Specific Goals

Also, I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing to be able to feedback to an elite athlete that yet again their scores have met the baseline markers we are looking for. Even if it is ‘normal’ for them. I used to stress about this when working with elite athletes as I really wanted something in the fitness test to show up as a weakness (or a strength) so we had a clear focus for the training. But actually the fitness test is simply an insurance policy- yes- you have a full bill of health. You have a strong foundation of general fitness on which you can build the plan. The specific goals then become more about the demands of the game and where the athlete feels they can make some extra gains.

Usually this can be about working with the physio to rehabilitate some niggling injuries, maybe working on a bad habit in terms of movement around the court and fixing that, or even doing some specific work to prepare for a change in game style. For example, if building more net play around your game style perhaps we need to condition the hamstrings more for some extra sprinting and stopping.

Corrective Exercise ”Pseudo-Physio”

My curiosity has peaked in recent months about sport biomechanics and I am even going to go to a 2 day course on pelvis function with Biomechanics Education. I recently read a great article on the Personal trainer Development Centre (PTDC) website (www.theptdc.com) titled, ”A Corrective Exercise Specialist’s Guide to Training Clients Through Pain.” You can read the whole article here.

He makes a really great point that first and foremost clients are coming to us NOT to take away pain but to gain a TRAINING EFFECT. It’s worth remembering that! Yes- we need to have an awareness of what movements elicit pain but more than that, it’s about having an arsenal of exercise variations and tweaks, and learning how and when to use which training technique to gain the desired training effect.

Think regress, not correct!!!

What movements can you still perform with them that work them hard, get them stronger and are pain free??

If you take your standard stock of go to exercises there are usually some common pain provoking exercises that can be accommodated with some alternatives. You’ll notice that a lot of the pain is during anterior loading of the knees or shoulder during pushing/pressing activities!!!

Example: Pain during Lunge Variations

Pain on Forward lunge or walking lunge- modify to reverse lunge or split squat lunge.

Pain on Split squat lunge (front leg)- use a shin block to promote vertical tibia. If back leg try foam rolling quads and/or use support under knee to reduce ROM. Or try a less upright posture and use more of a forward lean with a more pronounced hip hinge.

So my take home is that perhaps not every athlete needs a wildly different programme, but perhaps the individualisation comes from knowing which variation of a classic is best suited to each athlete.

Here are some further thoughts from Steve Magness on assessing versus guessing in the context of movement screening.

Steve Magness, author of ‘Science of Running,’ writes: ”The screens should be a part of our program to perhaps identify risks, but not lead to the robotic linear thinking of On test X you scored poorly, So you’ll have this problem, So we need to do Y rehab to correct this. The body doesn’t work like this- it’s a complex self-organizing system that needs to be challenged in a variety of ways. It needs to be challenged to figure out the best way forward, not trapped.”

Read the whole article Movement Screens. I highly recommend it. He basically says that the art of coaching involves knowing how the athlete’s body moves normally in training and noticing deviations away from that. This is as opposed to noticing how they move in closed assessment, and depending on whether it’s new or if it’s a simple versus dynamic movement, we’re testing something potentially far away from an athlete’s movement norms.

Athlete Monitoring

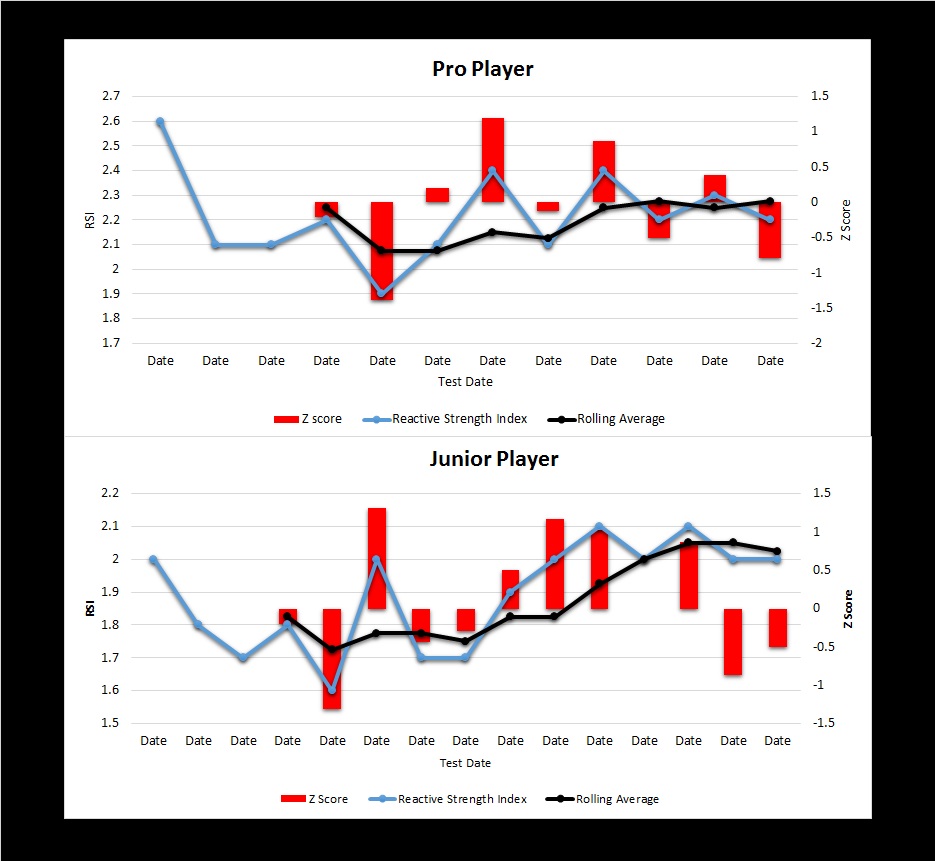

I’ve written about this topic on several posts. Lately I have been monitoring Z scores to note worthwhile differences in markers of performance, related to neural fatigue.

It’s early days but I’m going to stick with it for several months to make a real determination of its ability to tell when athletes are fresh or fatigued. So far I haven’t any athletes report a Z score of more than 2, which is the criteria for a significant worthwhile change from the norm.

In essence, we have the same issues with these tests where sport scientists are using numbers to determine readiness or prepardness. They provide some pretty little numbers, but do they really assess the issue we’re most concerned with?

Some will argue they don’t. What some suggest, is perhaps instead of needing to codify every single difference in movement or health marker, maybe we’d be better off by engaging in practice, paying attention to how our athletes move and look and building up a large enough bank of movement watching, that we can let our master pattern recognition software in our brain do it’s job.

As Steve Magness says, “Attention is the greatest commodity we have to give, and in modern society it’s often the first one to go. Watch your athletes from the beginning to the end of practice. Challenge them and see where the point of breakdown is, mechanically, metabolically, psychologically- and figure out how to address them. Simply being being aware will tell you more than any screen ever could.”

Right now, myself and the Head of Sport Science & Medicine I work closely with at the Tennis Academy have said you need to be at above 70% of your baseline markers to carry out a full training session. When you have recovered less than 70% (based on your health questionnaire used as part of your morning monitoring) training will be adapted accordingly. The health markers are subjectively reported scales based on muscle soreness, energy levels, muscle fatigue etc. If they report a drop in comparison to their 4 week rolling average that is less than 70% of that, we can advise reduction in volume and/or intensity or even complete rest.

The jury is still out. I still feel comfortable using both intuition and science to back up my hunches. I hope you have enjoyed my ramblings and have reflected yourself on why and what you test!!!! I’d love to hear your comments!!