What’s all the fuss about Velocity Based Training??!!

Last week I had the pleasure of spending the morning with my former lecturer Dr. Iain Fletcher. I love popping in to see ”Fletch” who oversees the BSc in Strength and Conditioning at University of Bedfordshire, is an external examiner for a number of Universities and is also a Tutor and Assessor for the UKSCA.

My original purpose of the visit was to get Iain’s take on the ‘Role of the University to prepare students for the workplace,’ as it’s a topic that I’m very passionate about. It was a pity that my video camera had a meltdown and I didn’t get us both in the shot- but what Iain had to say was really interesting and you should definitely check it out below:

Daz Dee TV Episode 9

But like all visits to see Fletch the topic nearly always turns to Strength and Power and I wanted to give you the low down on what we talked about. You see, as anyone who knows me will testify to, I’m a curious coach and I’m always questioning why I do things. If something doesn’t make sense it really grates on me so I have to seek out people and try and make more sense of things. The nuts and bolts of our discussion were focused on two topics:

- Strength endurance– why bother?

- Velocity Based training– who cares about Power any way?

At first glance these topics might not seem related- but on closer inspection I think there is a common element- our preoccupation with the need to do work, and the ability to do ‘more work’ in a given time.

I’ve previously written a couple of blogs on these topics:

Strength endurance:

Building Strong Foundations- Volume and Intensity

Do you need to build a Volume Base?

Power:

Gil Stevenson Workshop Lesson 2: The Science of Strength and Power

Why the midthigh clean pull is all you need to develop power

What is Power and have you got some?

Strength endurance

Strength endurance is a term I like to use which is similar to muscular endurance but is somewhat of a bridge between the classical 3×10 with incomplete recovery and the pure strength 5×5 programmes with full recovery. I’ve previously spoken about doing 5×5 prescriptions with incomplete recovery and calling it ‘strength endurance.’ But whatever you call it these type of concepts for me fall into the greater topic of work capacity.

The fascination with work capacity is there for all to see- many coaches believe you need to put in a foundation block of ‘work capacity’ training to have the basic level of fitness simply to be able to train properly for an hour with good quality. But what does this mean?

Work Capacity: definition

Workout Density: The amount of exercises, reps, and sets that are performed per workout. Think super-sets.

Density builds capacity.

In terms of strength qualities you will hear a lot of S&C coaches saying that you need to do a ‘strength endurance, anatomical adaptation, work capacity, strength foundation, strength base, robustness [insert other name] phase FIRST to prepare you for the higher intensity work to follow.

So onto my discussion on strength endurance. For years I have been sticking to my guns that 3×15=>4×10=>3×12=>4×8 (or something similar) is a nice progression for athletes to work up to the holy grail of strength programmes around the 5×5 range- where we start approaching and exceeding the magical 85% 1RM load.

If you go back through those blogs on strength endurance you’ll see I talk about how higher reps is better because it allows for more reps since the intensity is lower. This is great for skill acquisition and connective tissue adaptations.

But having spoken to Iain and also some personal communications with Alex Natera (senior S&C coach at Aspire Academy) they both said that you can still get the adaptations as long as the total volume load (sets x reps x load) is high enough:

Alex Natera- personal communication: 05/06/17

Rare cases and certain sports will have me chasing growth but most of the time I’ll push for growth using lower rep schemes, with higher loads and high total volumes.

Even in early GPP I shoot through the higher reps ranges with each week and by week 4 or so I am already down to 5’s.

Even in athletes who might not have “earned the right” I’ll still focus on quality through lower rep sets. I’ll get the volume in with increased number of sets instead.

He went on to say on how you develop strength endurance:

Agreed- for sure with this type of athlete endurance will be gained for getting stronger. When they are an advanced athlete then schemes for endurance based lifting may have importance.

Connective tissue responds well to high loads, and volume with high loads so don’t be too concerned about the anatomical adaptations purported to come from a 3×15 scheme. In fact most of the evidence for that comes from text books and articles looking at untrained or recreational trained.

Iain explained that you could use the 5×5 prescription but if you only give them 45-60 seconds rest between sets it will negate the desire to lift heavy and you can include several warm-up sets too so you are getting in the volume.

Iain said that for sports like rowing, cycling and even wrestling and so on where there is a need to have a lot of muscular endurance you could make a case for doing 15-20 reps at a time although if training time is limited you might as well let the sport take care of the endurance adaptations. For most sports that are acyclic you need to produce short bouts of strength, rest and repeat so he agrees with Alex on the way forward. Get to the 5×5 soon and use more sets and less rest and you’ll get endurance come along for the ride.

Power and Velocity Based Training

I’ve been thinking again about what are the key performance indicators that discriminate among sub elite and elite. I would normally always answer with the response, ‘Power.’ Lately I’ve been reflecting on this and an article that Iain wrote on Biomechanics made me question why we still put so much focus on Power.

Typical thinking about Power puts the emphasis on measurement of Velocity. Let’s look at why. Peak Power is measured during the concentric portion of the movement and typically occurs with a medium force and medium velocity.

Power= Work / Time

Work = Force x Distance

STRENGTH (Force) is required to produce work. So it follows that coaches value doing the same work in less time to develop power.

==============================================================================

Since Velocity = Distance / Time => Power = Force x Velocity

Going back to this idea that time is the limiting factor you can see why coaches are really concerned with velocity.

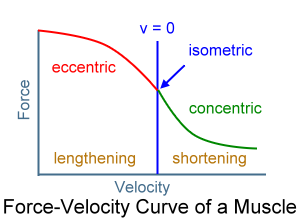

Velocity is concerned with the time to complete a given distance. It follows that we then want to focus on any exercise which might decrease the time to complete a given distance. Assuming that the distance is constant then yes, moving something in less time will increase velocity, which will increase Power. This has led to the proliferation of exercises like speed squats, speed deadlifts and speed presses, and the coaching cue of lifting ‘everything fast.’ But the problem is that these correlations with athletic performance are based on the concentric portion Force-Velocity curve without considering how the musculotendon unit functions in sport where there is usually an eccentric and isometric component.

We are focusing on how quickly the work is performed in the entire CONCENTRIC portion of the movement.

This is why something like a counter movement jump will produce very high power outputs if you can jump higher but to do this you will have a slightly longer jump cycle (time on the ground) which you will not be rewarded for in most sports actions.

These type of moderate load speed exercises which emphasise the concentric muscle action make sense for ballistic striking actions like punching, kicking and even hitting a ground stroke in tennis where there is little to no external resistance other than your limb. But this isn’t the full story!

Assessment of the concentric portion of the curve does not grasp the underlying principles of acceleration which states that accelerations are linked to the production of Force. The F-V graph doesn’t account for HOW we produce that force.

Acceleration = the rate of change in velocity and Acceleration = Force / mass.

I think we need to start thinking about the increases in how the forces are occurring over the entire sport movement, not just the concentric portion of the F-V curve. The forces required for sports movements which involve displacement of our ENTIRE BODYWEIGHT in time frames of less than 250 milliseconds are huge.

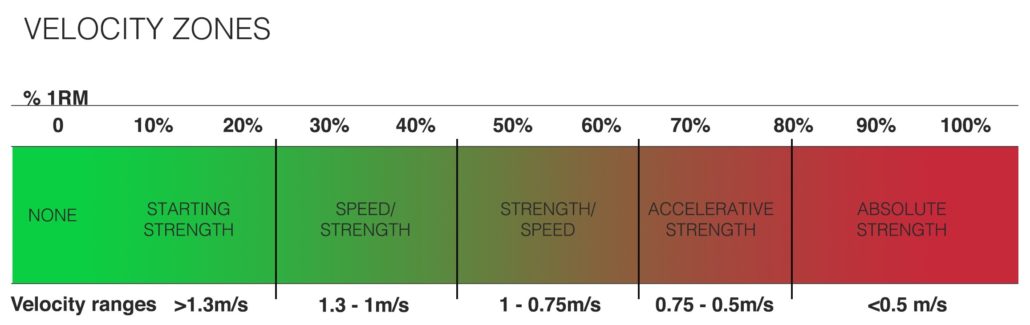

If we only focus on the velocity component we might focus on doing things like jump squats with 0-40%1RM loads because that would produce the greatest bar speed in the concentric phase, believing we are training acceleration optimally. This is often called ‘starting strength.’ I personally don’t like this term. I think it is fine if you are using these loads to augment improvements in the fast striking actions or even eccentric loading of the tendon- which we will talk in more detail below.

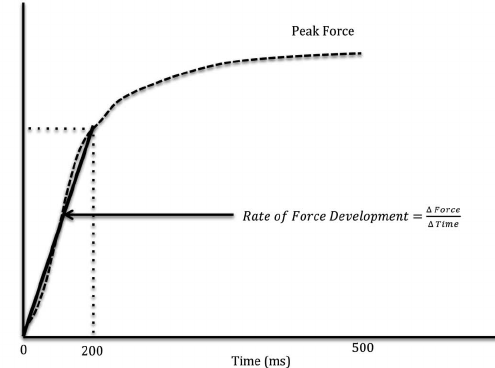

I think we need to put more focus on what happens at the onset of the concentric contraction, particularly when it takes place as part of a ballistic movement involving the stretch shortening cycle, or at the onset of movement from a stationary position. The graphic below really captures for me the difference between acceleration and velocity.

When a pendulum swings from side to side, its velocity and acceleration vary — both in magnitude and in direction — at each point during the motion.

The magnitude of velocity of a pendulum is highest in the center (think ‘power’) and lowest at the edges. On the other hand, the magnitude of its acceleration is highest at the edges (think ‘Rate of Force Development’) and lowest at the center. For me this is like what we do when we focus on velocity and power- we look at the velocity at the middle of the movement at the concentric portion. But the acceleration at the start of the movement is key in the initiation of the concentric muscular contractions.

Scenario 1: Onset of Concentric Contraction: Heavy Load

If you are trying to improve your ability to start better as in ”get off to a good start in a 100m race” I would put emphasis on heavy isometric loads and heavy Olympic lifts- where you will need to gather large forces quickly, as well as traditional heavy strength lifts such as the Back squat at >85% 1RM. When you have to accelerate your body from rest you will have more time to produce higher Forces.

The heavy strength exercise will help with initiation of movement and the explosive strength Olympic lifts will help with acceleration over the first few strides during acceleration.

The forces on heavy strength lifts will not be associated with high velocities but the intent to produce maximum rate of force development (RFD) will be!!!

According to Mel Siff- starting strength occurs isometrically before the load is moving.

Scenario 2: Onset of Concentric Contraction: Light Load

Most sporting movements take place in less than 200 milliseconds- we have limited time in which to produce force in order to be competitive. We know therefore that being able to produce force quickly in order to accelerate our body and other objects is vital.

In order to produce the required High Forces in only a few hundred milliseconds relies on the eccentric storage and release of energy in the tendons while the muscle tries to maintain an isometric contraction- until the point of release of energy in the concentric phase. This is why ballistic exercises that utilise the ‘Stretch-shortening Cycle (SSC)‘ are more correlated with athletic performance.

The SSC is associated with a Rapid rise in Force as measured by the Rate of Force Development (RFD). Remember that this concentric measurement occurs after the eccentric loading. In this type of work Plyometric drills are most suited.

What are the Best Exercises for developing RFD?

Both plyometrics and Olympic weight lifting exercises are a great way to obtain RAPID impulses as measured by the gradient of the Steep part of the Force-Time curve above. These activities are represented at opposite ends on the concentric part of the Force-Velocity curve for simplicity sake. But in reality both are associated with a massive build up of eccentric force on the left side of the curve before delivering the concentric output on the right side of the curve.

Dan Baker- Exercises can be deemed by their biomechanical attributes as either “strength” or “power” oriented. In power exercises, the velocities are high and acceleration continues to the end of the range—the forces do not have to be decelerated. Basically the energy is released into the air through jumps, hops, and throws. Olympic lifts also fall into this category (they are jumping exercises, essentially). If the force is safely dampened at the end of the movement, like hitting a heavy bag, then throwing punches and kicking are also power exercises.

Strength exercises have a deceleration phase at the end of range when resistances are low (< 50% 1RM)= to avoid stressing the tendons and joints. On major strength exercises like squats, bench presses, and deadlifts, with resistances below 50% 1RM, more than half the ROM is spent in deceleration, making them less than ideal for power training even though at this low level of resistance the velocity may be high.[agrees with my previous comment about the practicality of speed squats and deadlifts at lower loads]

The length of the deceleration phase decreases as resistances go above 65% 1RM. By 85-90%, there is no real deceleration phase, but the velocities are so low at this level of resistance that they cannot be classified as power exercises. So using light resistances below 50% 1RM in traditional strength exercises to develop power is often counterproductive as it is training the body to decelerate for much of the ROM, rather than continuing to accelerate.

So we do strength exercises with heavy resistances to develop force/strength, and power exercises with the appropriate resistance to train the body to use force with high velocity until the end of range. If you want to use “strength exercises” to develop power, you need to use resistances of 50-70% 1RM. Something to dampen the ferocity of a rapid lockout (such as bands and chains) also helps.

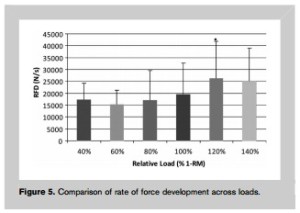

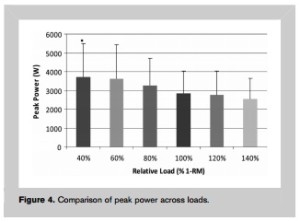

The results of the study below nicely summarise what I have been inferring to in this blog- peak power (watts) is produced at the lowest load for the mid thigh clean pull (40% 1RM power clean) whereas the highest rate of force development (N/s) was produced at the second highest load (120% 1RM power clean).

J Strength Cond Res 26(5): 1208–1214, 2012. This study specifically looked at the force-velocity characteristics of the mid-thigh clean pull across a range of loads.

Peak Power across loads

When training to maximize peak power output, lower loads are recommended. Moreover if the goal is to train force, impulse or RFD higher loads, of 120– 140% 1RM, are recommended

And Finally……

I couldn’t do a post that mentions Dr Iain Fletcher, Dr Mike Stone and Alex Natera and talk about strength training without giving a quick shout out to my friends at Emerge Fitness in the USA, who specialise in provided training products for serious strength athletes. They have some great knee wraps for weightlifting. Check them out HERE.