Pacey Performance Podcast REVIEW- Episode 297 Cam Josse

This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 297 – Cam Josse

Cam Josse

Background:

Cam Josse

Cam is Performance Coach for American Football Indiana University since March 2020, and spent most of his career in the private sector, most notably at DeFranco’s Training from 2013 to 2020.

Discussion topics:

What are the benefits of Max Speed training for Team sport athletes?

”I will never argue that team sport is acceleration dominant in nature, your bread and butter is going to be your ability to accelerate. But through the research I have done and talking to researchers like Ken Clarke, who has done a lot of research on top speed, I have the approach to training that I don’t want to leave any stone unturned.

So what are some of the benefits we are seeing from maximal speed training?

- It is going to affect your entire speed curve- if you can be faster and hold onto that top speed then you are going to be faster at every segment below that

- The biggest game breaking plays are going to involve these explosive longer distance runs over 60 Yards and they are in a high speed environment where often they struggle because they don’t know how to cope with the dynamics in that environment. Even though they are very rare that doesn’t mean we should neglect them.

- It is so neurologically unique there is no other way to really operate and train that. We can’t do much in a weight room setting, or outside of achieving top speed to help the athlete develop in that environment. It’s a very elastic environment (in contrast to the more muscular actions of acceleration).

- Developing ability to active and utilise the elastic components and not just the muscles is going to protect their structures.”

Why do you focus so much on the split times, such as 10 Yard segments?

”When I look at the different segments to me it paints a picture and tells a story, and every 10 Yard segment is going to tell you a different story. Just looking at the 40 Yard sprint and the total time we see the outcome but we don’t always see the story of how they got there.

- First 10 Yards – high force production and horizontal orientation (strength-speed)

- 10 -20 Yards – you will see the pure explosive qualities coming to light there (speed-strength)

- 20-30 Yards – reactive and elastic ability

- 30-40 Yards- max speed ability

At a recent study of NFL combine in 2016 everyone was at around 95% of their maximum speed by around 20 Yards and obviously the ones who were faster and had better velocity capability were at a lower percentage of their maximum speed because they could spread it further, but some of the slow or stronger guys like linesmen were almost at 100% by 20 yards.

The only way I think you improve the segment beyond 20 Yards is sprinting at high speed, I don’t think there is much of anything else that is going to help develop that further.

With regard to the exercises that might be associated with different segments Cam used the example of someone dominating the triple broad jump, you are probably someone who is going to be very powerful and have longer coupling capability- meaning you are able to produce power over large ranges of motion with your hip, knee and ankle. You are probably going to dominate hill sprints, light resistance sprints. You have a lot of power against lighter resisted activities.

Once you go beyond 20 Yards that’s where the benefit of some of those more general activities start to fizzle out. I think you have to make it more specific to what is happening on the field. Some plyometric activities such as long bounds, or dribble runs (A runs) and shorter coupling activities where you are working through shorter ranges of motion and truly elastic, truly plyometric activity, you’re probably still going to be good up to 30 Yards.

Beyond 30 Yards it’s about how well you operate at >95% of your maximal speed capabilities.

Do you think there is an overemphasis on ”drilling” of speed in the team sport setting?

”Yes 100% and I have been guilty of that myself, I have learnt a sprint technique and feel like I have this secret sauce, so now I’m going out seeing all these athletes and saying he sprints like shit, and if they were in my programme I would be able to work with them! I think that the problem is, a lot of coaches just want to be heard because we are passionate about what we do, and like to feel like we have some influence over our players.

Know your role! We are facilitators not dictators.

We give them hints and provide them with environments that they can then utilize and develop themselves to realise their own potential; we are not here to just hold their hand.

I can give you an example of some work with an athlete I did a few years back who was getting prepared for their NFL pro day. I was not able to attend his pro day. I hand held him through the entire process of training, I over drilled him, I over cued him, I was constantly just like if he made one small error I had to fix it there and then! Needless to say, he went to his pro day and I was not there to hold his hand and he completely shat the bed! He needed me to tell him what to do at every segment of the run. That was where it hit me that I didn’t give him ownership of his own develop!

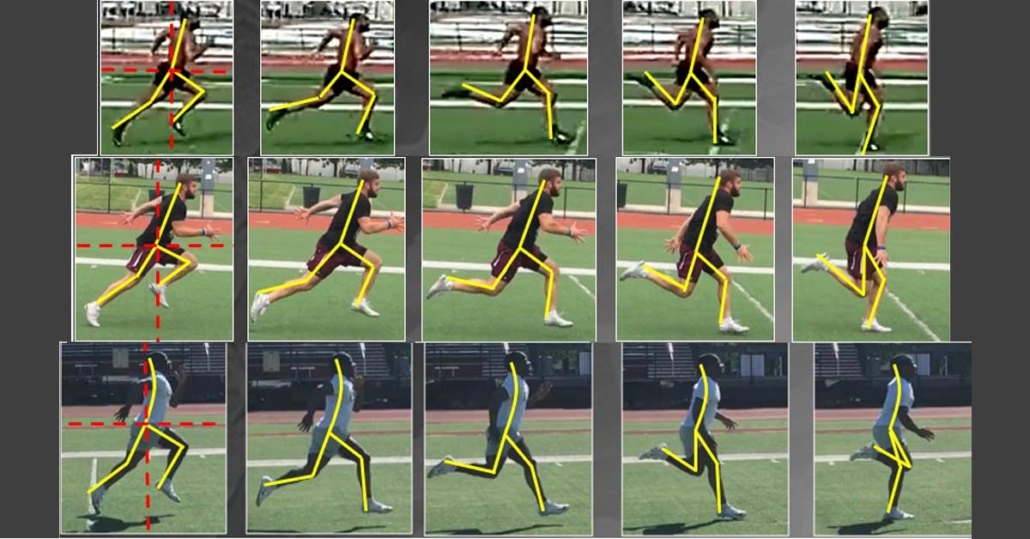

Look at what are the stable components of movement (attractors)- so for example, how do we get them to understand how to create a positive shin angle in acceleration, maybe it’s not a cue at all from the coach, maybe its to use some resistance so they can feel it. Or maybe for change of direction, a general principle of movement is to lower your centre of mass (COM) towards your base of support (BOS).

So that’s where we do look to track & field for that specific context. It’s not that we think it’s a cure all that if someone just runs the fastest linear sprint possible they will be a great team sport player, because I think we can all agree that is absurb, otherwise we would just try and get Asafa Powell and Usain Bolt to play football!

- Cueing to make them realise where their limbs should do in time and space- but it’s very rare that this would fix it alone as they have been doing something a certain way for so long

- Cueing to develop Force application into the ground – getting the athlete to understand a concept using motor term descriptors such as ”pop off the ground” when you are at top speed. Another cue is imagine that the ground is getting hotter and hotter with every step you take. I prefer pop to punch, as the athlete can sometimes punch far too hard, and it wasn’t smooth, fluid and graceful. Punch is a better for acceleration, as it’s more aggressive.

- Cueing to think as if you are running upstairs as you move towards the horizon- it seems to promote front side mechanics better as when you run up stairs you have to have great front side mechanics!

- Drill/cue- Med ball punch run (4-6lbs) held in front of their body right around the level of the navel and then I just tell them to run and try and contact your quad to the med ball. It promotes a cyclical high knee activity which is very similar to top speed sprinting (similar to Altis who use the dribble run). With the med ball you don’t need to go full speed but it just gets them used feeling what it feels like to achieve that front side lift, and it gives them something to aim for. They may feel a weakness in an ankle when the limb comes down from that kind of height as they are not used to transmitting that much force through the ankle.

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Importance of speed reserve- increasing top speed is going to affect your entire speed curve- if you can be faster and hold onto that top speed then you are going to be faster at every segment below that

- SAID principle- to get faster at top speed the only way I think you improve beyond 20 Yards is sprinting at high speed, I don’t think there is much of anything else that is going to help develop that further.

- Know your role! We are facilitators not dictators- it’s better to say no little than too much.

- Top speed isn’t the cure all- we don’t think that if someone just runs the fastest linear sprint possible they will be a great team sport player, because I think we can all agree that is absurb

- Find cues that work for your athletes

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

Twitter:

@IUcoachJosse

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM