Best Speed & Plyo Drills for Acceleration – Part 1

It’s been a little while since I’ve posted a blog, which has been down to several different reasons.

Firstly, in July APA were officially offered the contract to run the strength & conditioning programme at Bromley Tennis Centre.

This is an incredible opportunity for APA to continue our work in supporting elite junior tennis players in the UK and so I was hard at work behind the scenes in late July and early August interviewing for the Head of S&C role and two assistant coach roles. This was on top of my interviews for the next intake of APA interns, of which I had selected four coaches who will be based at Gosling Tennis Academy.

Secondly, I have made a conscious decision to spend a little less time on social media so my posts have been less frequent across all means including this blog; and thirdly, to be perfectly blunt, I want to share things when I think I have something noteworthy to share!

As it relates to noteworthy topics I was given a recent nudge by one of my athlete’s father, who is also my business partner on the Junior Player Fitness App who recently asked me how my unofficial PhD was going, referring to my research to underpin the APA Method, that I hope will help transport APA to being regarded as the ”Best Tennis S&C Team in the World.”

You might recall I broke the research into four areas:

- Movement

- The Serve

- Ground strokes

- Tennis Match KPIs

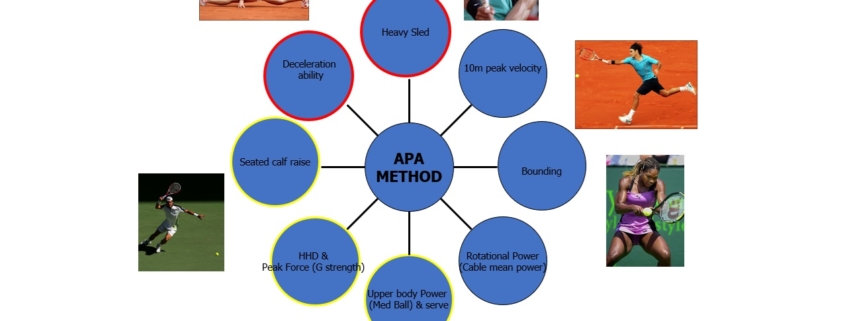

I recently created a mind map to help me brain storm methods to research further that I think will take the APA Method to the next level, and help us to stand out as the Best in Class for what we do.

So I thought it was time to give you an update and home in on a topic that has recently peaked my interest – ”bounding.” I see this as being one of the key elements as it relates to Movement. In this Part 1 I want to introduce the background (the ”Why”). In Part 2 I’ll focus on the jumping drills – bounding (the ”How.”). Finally, in part 3 I’ll discuss the speed drills – acceleration (the ”How.”)

Best Speed & Plyo Drills for Acceleration

Background to the Blog

After I did the research on Tennis movement there were a few things that were left unresolved in my mind in terms of the best approach to develop movement, and specifically acceleration. However, it seems like a lot of pieces of the jigsaw puzzle have started to fall into place (the world seems to have a canny way of creating opportunities like that if you are ready to receive them). It started with some useful insights in an old instagram post from Alex Natera on his preferred stationary drills to teach Acceleration. This was quickly followed by specific guidance on bounding from US High school Coach of the Year John Garrish in a Pacey Performance podcast. Then most recently I caught another podcast with Mike Boyle (Strength coach Podcast Episode 342) and I read an article on sportsmith on ”shin roll” and its importance in Acceleration.

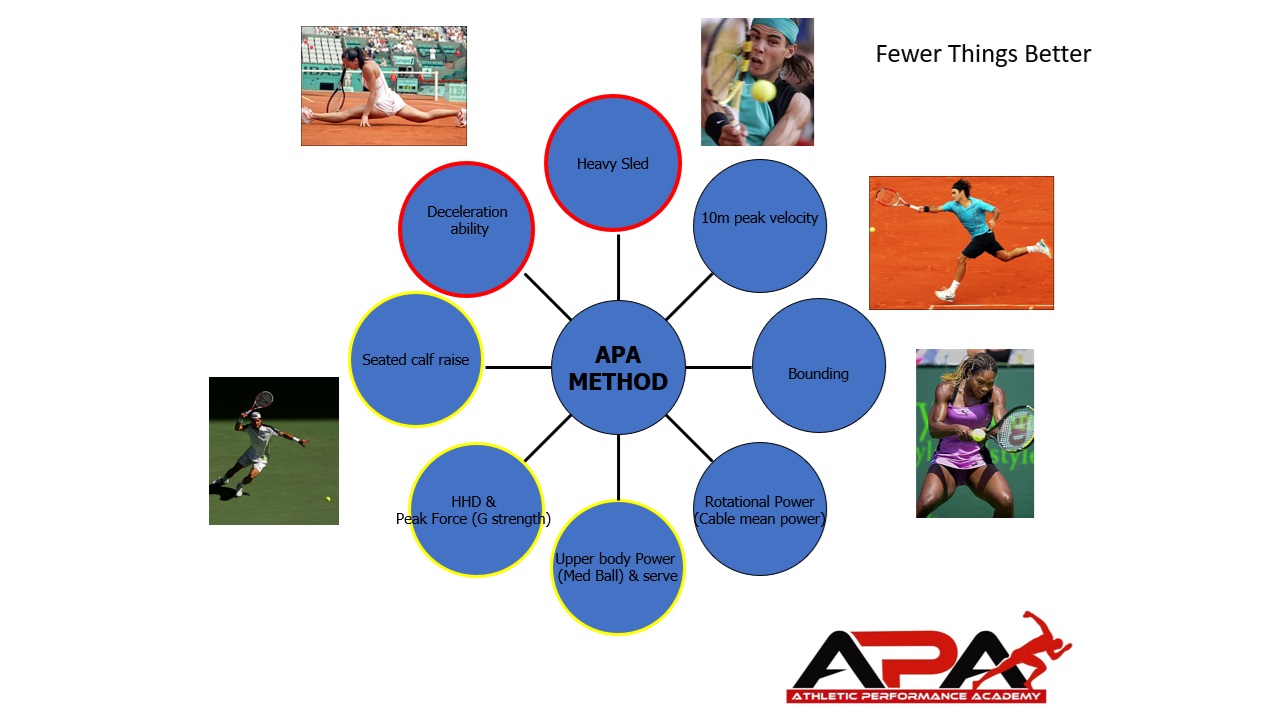

My interest in this topic as owner of APA, is focused on selecting exercises for the APA Method that make the biggest impact on the Movements that Matter.

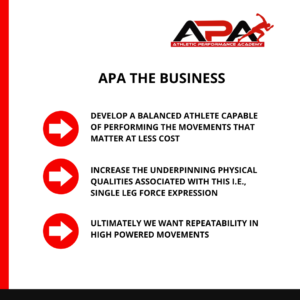

I have been reluctant to utilise methods whole heartedly until I have understood the biomechanical and physiological underpinning qualities associated with them. So that’s why I first did a review of all the Power research (see some of the articles on Triphasic Method, the Force-Velocity Curve for Tennis, and Weighted jumps.)

This enabled me to review the APA Method for Strength/Power and the exercises suitable to develop: Maximum Strength, Explosive strength, Ballistic strength and reactive strength.

Acceleration Development

This blog will focus on the most recent research I did on jump exercises that aid in acceleration development, so those jumps that aid in deceleration will be addressed in another blog.

Most people assume that when I am talking about jump training, I’m talking about ‘plyometrics.’ However, I think it is important to highlight at this point in the blog, that not all jump exercises are plyometric (even though I mention plyos in the title of this blog)! When you look at the movement demands of tennis you find there are jumps occurring where emphasis is on the concentric part of force production.

I also want to be clear on what type of tennis movement I am specifically referring to by breaking down the tennis movement into different phases that characterise tennis sprints. For example, to quote Matt Kuzdub, ”an elite 100m sprinter might reach maximum sprinting velocity between the 50-80m mark while a tennis player needs to reach their highest attainable court speed within a 5-15m distance. And all these sprints still require that the player gets off to a good start.” I like that Matt refers to it as top (court) speed instead of max speed or top speed.

In a 15m sprint to get to a drop shot, there are different phases that characterise the sprint:

–> the start (0-1m)

–> the acceleration (1-5m)

–> the top court speed (5-10m)

–> the deceleration (10-15m)

For the purpose of this blog, I am mostly talking about the physical qualities associated with ”acceleration.” For ease of explanation I’ll include both 1-5m and 5-10m as acceleration in my definition.

Maximum Strength- (First step speed, 0-1m)

Force production

Force production demands are highest during the initiation of movement (after the serve and after the change of direction from a wide ball), as well as when the player is wrong footed (see below).

The so-called ”starting movements‟ executed without ”counter-movement‟ (for example: the body’s static inertia) are best trained against heavy resistance in my opinion, and the major role is played by Maximal Strength and the Explosive Strength, expressed in an isometric regime.

For the most part, this form of force production will be addressed best with heavy strength training, but we can use jump exercises that start from a stationary position (without counter movement) and emphasise concentric only actions – such as:

–> Single leg hops to box

Explosive Strength – (Acceleration, 1-10m)

In the sport of tennis there are various actions that place high requirements on explosive strength. Leg drive on serves, and the take off phase of big ground strokes, as well as the initial acceleration to the ball, to propel the body in the direction of the ball over the first 10 metres (see below).

Matt Kuzdub refers to this acceleration ability as their top ‘court speed.’ We want players to hit their top court speed as soon as possible when tracking down tough balls (drop shots, angled shots, wide balls, serve and volley, lobs etc).

- When the explosive movement is executed with ”counter-movement‟, i.e., in the reversal yielding-overcoming (“eccentric-concentric”) regime, the major role is played by the Explosive Strength expressed in the overcoming (“concentric”) regime.

- Acceleration to the ball – when first moving to the ball following the split step we’re actually not moving fast at all, but we are generating high forces. The initial acceleration to the ball requires explosive strength. Those first several strides are characterised by longer ground contact times. The more force we can develop in these first few steps, the faster we can displace ourselves. Explosive Strength expressed in the overcoming (“concentric”) regime will be a key physical quality.

Think Olympic Lifts (80-90% 1RM) and Back squats 60-80% 1RM with 2-5 reps occurring within a given set and complete rest being achieved after each set.

I personally view high force – high speed methods like Olympic lifts and explosive back squats (aka 55-80 power phase after Triphasic method in Cal Dietz training model) as ”best fits” to develop the explosive strength required for the initial acceleration (1-5m) to the ball. This is based on the assumption that the player is performing a full sprint such as when chasing down a drop shot!

I’m thinking that Heavy Sleds might be a good fit here but I haven’t incorporated them yet so watch this space

I may also do some concentric enphasis plyos – I’ll leave you to argue if they fit better for First step or Acceleration (or Alex as he is far smarter than me):

- Weighted Squat Jump

- 1 leg Smith Squats to box

- Bungee Broad Jump

- 1 leg Broad jump to low box

- Box hop onto high box from box sit

- Loaded stair bounds (weighted vest)

- Resisted block start – bungee

- Resisted acceleration – sled

Thanks to Alex Natera for the inspiration for the exercises above.

Ballistic Strength

In the sport of tennis there are various actions that place high requirements on ballistic strength. Acceleration phase on serves, and ground strokes, as well as most tennis movements within a few metres. Think:

–> Loaded jump squats (30-60% 1RM), med balls and slow SSC plyos

The majority of tennis movements are performed using ”footwork” patterns such as side shuffles and cross-over steps as well as steps towards the ball where there is more hip and knee flexion and more time in contact with the ground (such as a wide running forehand). Therefore slow SSC plyometrics fit well here- with emphasis on hip based jumping exercises.

How To Hit the Running Forehand

I’m not going to talk in this blog about reactive strength. In the sport of tennis there are various actions that place high requirements on reactive strength. Racket head speed on serves, and ground strokes, as well as tennis split steps and most lower intensity movements that don’t require you to move much at all. Think fast SSC plyos which are also useful for top speed sprinting (although top speed is not specific to tennis).

As it relates to Ballistic Strength and slow SSC plyos, I wanted to get a bit more clarity on the type of plyometric activities we could use for the APA Method. I want to focus in particular on the wide running forehand. I have to give Jez Green and also Dave Bailey credit for putting me on to the idea many years ago, that the running forehand is more like a triple jump (from track & field) than it is like a sprint.

There is a clear conversion of horizontal force into a vertical force effort (at ball contact) and I just think it’s one of the shots (which has a specific footwork technique) that sign posts the S&C coach to a type of plyometric activity that would fit best with such an important movement in Tennis. It’s not a full out sprint (so the technical model for acceleration doesn’t quite fit) and it only requires movement over a few metres; so what could we use to overload the skill of hitting a running forehand beyond just practising doing the shot itself?

And that’s when I get to the 3 Hop for distance……

John Garrish – Bounds for Distance

If I’m totally honest I stayed in my comfort zone for most of my career when it came to bounding – meaning, I didn’t do any with Tennis players. It was on my ‘To Do List’ to spend some time with local track & field coaches. But no matter how hard I tried to hide from them, bounding kept showing up in my socials and coaches I respect kept mentioning them.

I stick to my mostly bilateral jump progressions but then I catch two podcasts in the space of a few weeks – John Garrish talking about bounding and Mike Boyle talking about the 3 Hop for Distance, so I decide to get to grips with this! Before I get specifically into the 3 Hops for Distance I’ll talk more generally about bounding first.

The podcast with John put me onto his instagram where he has done a terrific job of explaining the differences between bounding and max velocity, and also the biomechanical differences between speed bounding versus bounding for distance.

Speed bounds and bounds for distance are quite different, both intentionally and technically. Speed bounds more closely mirror sprint postures and the mechanics of acceleration. John recommends Bounds for distance first, to clearly differentiate bounding from sprinting.

Bounds for distance – hind-foot

A couple of takeaways from the Instagram posts:

–> The #1 cause of shin discomfort is ball/toe first bounding, rather than hind-foot contacts

–> We see hind-foot contacts in many sporting movements

–> Power skips, approach jumps, dunks, headers, high jump, long jump

–> But bounding progressions are harder to master (gallops and skips) because the penultimate step in these actions (the initial ground contact after flight) is more stiff on the front of the foot

–> This is especially true when using ‘for distance’ (vs. ‘for height.’). The second ground contact (the leg that will perform the jump) will be heel first, rolling ground contact.

This also helped me develop a framework for introducing bounding into the APA Method:

Gallops –> Power skips –> Bounding

In terms of the progressions within bounding itself:

Lateral bounds –> In place Vertical bound –> Forward (heel) hops –> Forward into Vertical hop –> Hop Bound Combo

I’ll give examples of all of these in Part 2 of the blog.

Mike Boyle – 3 Hop for Distance

Finally, I just wanted to touch on what I heard Mike have to say on the topic of 3 Hop for Distance.

Mike posted on twitter, ”Would you ever actually do a unilateral hop for distance if you weren’t testing? I’m curious. We only hop for reactivity and height, never distance.”

I love that Mike says that sometimes like a lot of people, he is looking for a little bit of validation, ‘Is this odd, or am I odd?”, when he looks at that idea. So I hear all these people say you have got to do this lateral hop, and 3 hop for distance and multiple hop whatever…and all these return to play tests. And does anyone ever programme these tests in when it is NOT a return to play situation? So that was the question.

Mike doesn’t. Mike’s plyometric programme is generally not based around max effort jumps or hops.

”So we don’t say I want you to do 3 hops on your left leg and try to cover as much ground as you can. We will generally lay out three hurdles that are layed out at a set distance and then get that athlete to negotiate their way through the three hurdles. And so, the ACL world is weird as there is a lot of emperor wearing new clothes (meaning a situation in which people are afraid to criticize something because everyone else seems to think it is good or important).”

Why would you do it for rehab if you don’t do it with your healthy athletes?

People don’t want to speak up and they don’t want to ask the questions that I’m asking right now in terms of why did open chain stuff come back, why are we testing and listing a return to play test as important, as you never did it before, never did it in training and you will never do again, and yet that is going to determine whether or not you are ready to play? I think that is very odd. So a 3 Hop for distance or a single leg vertical hop left and right are not really trained, and the reality is that they are not being done in a lot of return to play training programme that I’m looking at and yet suddenly they pop up as tests. I just think that is a bit strange.”

Mike feels we don’t do repeated (3 Hops) in sport.

”Okay you might get at some point a 2 Hop situation in sport where you land on one leg and then you stutter and hop again and you land on the same leg, but in general that’s not done. Running is opposition, running is right to left, is basically a bounding action versus a hopping action. So when people use the 3 Hop for distance to help athletes run fast I don’t think that is a good argument because multiple take offs and landing on the same leg is NOT normal. In triple jump you do, but in general it doesn’t happen, you don’t see multiple hops.

I get that you need to do multi hops but do I need to do that for maximum distance, because now there is exposure to gravity and flight time etc and I think it gets a bit dicey when you add the distance component.”

Mike also doesn’t like Broad Jump for maximum distance for the same reason because of the risk of straining your ACL (or similar) when you get competitive guys to do competitive things – such as trying to hit a PB in a SBJ preparing for the NFL combine. It can end badly when you are trying to extend your SBJ out and perhaps land in a heap on the ground in a ball with ass to grass.

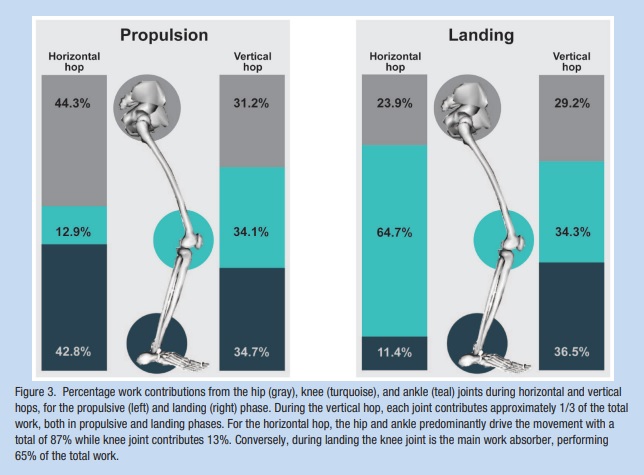

I feel like this has already become the longest blog ever on justification for bounding, so I’ll pretty much leave it there. But before I do, I’ll just give you this journal article for your consideration – Vertical and Horizontal Hop Performance_contributions of the hip, knee and ankle

Percentage Work Contributions from the Hip, Knee and Ankle

I think that if the goal is to develop hip based jumping exercises then probably the 3 Hop will be good in that regard (horizontal hop has 44.3% contribution from hip). But given that there is little contribution of the knee in a horizontal hop I’d be inclined to use a horizontal into vertical hop, in order to better recreate the expression of force in a wide running Forehand. I think the vertical component of the leg drive up into the ball (34.1% contribution of knee in a vertical hop) will be important.

And if I’m looking for a plyometric activity that best prepares for a more extreme ”running Forehand” I’d be going to bounds for distance…….

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM