A few weeks ago I was asked to be interviewed by one of the students who is doing work experience with APA, as part of one of his assignments for University.

I thought it might make an interesting blog post- I’ll leave you to be the judge of that!!

Coach- Athlete Relationship Interview – Daz Drake

- A little background history, how did you develop an interest in getting into the field of strength and conditioning?

I’ve had a fairly traditional route into the field of strength and conditioning. My interest in sport has been there from a young age, in football, athletics, long distance running etc. I probably realised early on that I wasn’t going to be a world beater, in terms of being an athlete. So I went to University to complete my degree in Sport Science, and from there went on to do my gym instructor and personal training awards. Once I left University, I realised it was all about networking. At the time one of my best friends happened to run a tennis club, and was looking for someone to do circuit training, of which I was capable of doing. It inspired my curiosity to learn more about how to train athletes rather than members of the public. I was at the inaugural Olympic weight lifting course that Sportscoach UK delivered in 2003, which would then develop into the UK Strength and Conditioning Association workshop, so I was actually there at the very beginning. I went from working in a local tennis club to getting my very first job here at the Gosling Tennis Academy (again through meeting someone at the UKSCA inaugural 2004 conference). I have now been involved here for 11 years.

- From a young age, who would you say were your idols, or anyone that would have a big influence on your life/career?

I would say I never had a single person that I would call an idol or role model. Of course like all young males I too dreamed of being a footballer, so in that sense I would my say idol as a young kid was Ian Wright. However I never had a specific aspiration to emulate one of my sporting heroes, as equally I’ve never had a coach or mentor that I would single out as one particular inspiration for me. My entire coaching career has been one big journey of self-discovery and learning independently by doing (Erickson, Bruner, MacDonald, & Côté 2009). Everything I’ve learnt has been self-taught, and rather than having one particular coach that has mentored me, what I tried to do instead was create a leadership group, within my network of people that I trust who have had more experience than myself in other areas, and who I have always been able to ask questions of and go and visit. Rather than trying to become an expert in everything, having that leadership group is key because personally you can never know everything about such a broad field like strength and conditioning. There’s a business book called ‘Think and Grow Rich’, by Napoleon Hill (Hill, 1937) , and one of the thing he said was that even the greatest and richest people in history have always been reliant on the expertise of people within their group, and that in a way is what I’ve done, is put together a group of leaders and experts around me of which I can gather ideas from, otherwise I would not have been able to carry out this job on my own.

- Would you say there’s any one individual who you take inspiration from in terms of replicating their method/philosophy of coaching, or would you take different elements and characteristics to make them your own?

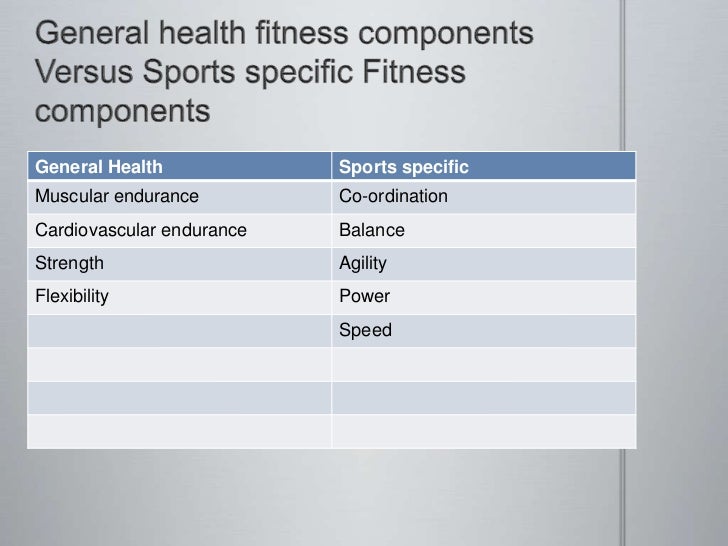

There’s a quote by Ralph Emerson who said ‘As to methods there are many, but as to principles there are few’ , so personally I have always tried to get a grasp of the principles of training which I think are not unique, as all of the best trainers in the world respect the principles of training in terms of; overload, variation, specificity etc. But when I was setting up the company, and taking myself from just doing my programme, to then wanting to be a leader and influence other coaches, I was much more aware that I needed to have a stronger and clearer philosophy that I could articulate to the other coaches.

Not rocket science I know but I actually spent around 18 months figuring out where all the various types of fitness could fit inside the 5 S’s:

The late, great Mel Siff often referred to the Seven S-factors of fitness. The S-factors include:

1. strength

2. stamina (general cardiovascular endurance and local muscular endurance)

3. suppleness (flexibility)

4. speed

5. skill (kinasthesis, motor coordination and control)

6. structure (size, shape), and

7. spirit (psychological fitness)

I stick to 5 and prioritise:

- suppleness

- skill

- strength

- speed

- stamina

I always think that the foundation of fitness is movement efficiency.

1 + 2 = foundation (movement efficiency)

3+4+5 = fitness

A note on stamina

About 5 years ago in terms of figuring out my philosophy one of the key influences was veteran strength and conditioning coach, Vern Gambetta, and running coach, Jarrod Deacon both of whom implement the short to long approach in terms of developing endurance, suggesting that you want to increase the speed you can run, and then having developed a good economical running speed, you can then increase the distance at which you can maintain that speed (Ferrigno, 2014). So the short to long approach is a big part of the tennis philosophy that I’ve developed here.

A note on suppleness

Another key influence would be another veteran coach, Mike Boyle, and one thing he said was the joint by joint approach, relating to mobility and stability, and which of these three elements body parts require e.g. ankle (mobility), knee (stability) etc. so this was a better way of helping me understand how to training the kinetic chain of the body as efficiently as possible. Eric Cressey from America, who works with baseball players, was one of the first people that gave me a blueprint for how to do good, quality sport specific training, as the emphasis is on having a good understanding of the needs of the sport and how to best prepare without just trying to replicate movements and shots of the sport.

- What age range of athletes do you primarily work with currently, and would you say you have any preference regarding what category of athlete you coach?

Currently I work a little differently to how I have done in the past, as previously I made sure I worked with every kind of age group, as young as 5 years old up to 25. More recently I don’t tend to work with the youngest age groups as now I specialise in the juniors that are transitioning into professional sport (12-16), the other fifty percent of my time would be spent with those of elite standard that make a living out of the sport. I believe there is a misconception of whether it may be an easier or harder job depending on age categorisation as I believe everyone is unique. In previous experience, irrespective of age or standard you get those that gravitate towards fitness and enjoy it more than others. Therefore I don’t have a preference as everyone brings different challenges, who all bring enjoyable experiences for different reasons. In a way I enjoy the challenge of working with those who may not enjoy the training as much initially, because then you really have to test yourself to get them to change their mindset.

- When being introduced to new athletes, what would be the key factors in ensuring a positive/safe environment in which they trust and respect you? Does this depend on age category?

In terms of the safety element for athletes is about appropriate exercise prescription and level of training depending on the level of physical development, so what you’re asking the athlete to do is not going to be injury provoking. As you say, the trust and respect elements are key for the training environment. For me, firstly it is about how the coach themselves making sure they develop a positive environment. It needs to be about the coach being animated, inspirational and in general being passionate and excited about what you’re doing. During the sessions it is important to search for the positives aspects of the athlete’s performances and give genuine praise about the good progress they make, as sometimes it’s too easy to spot the negative aspects and look into the reasons as to why they’re not doing well.

I believe respect comes from three different areas; knowledge, authority and power. You need to initially possess the knowledge and display to your athletes that you know what you’re talking about, as they more often than not will respect you if they believe what you’re asking of them is helping them to get better and ultimately win. Generally there is a sociological hierarchy, in which adults are generally thought of as having more authority and power over children, so naturally young people are generally brought up to respect those older than them. However you should never rely on believing you should immediately gain respect based on a hieratical ladder, and you need to earn it, because ultimately if you don’t know what you’re talking about then you lose respect very quickly. As a coach you need to be very clear about what your boundaries are and make sure the people under your care are made aware that if they cross the line that they know there is a consequence for their actions. Of course people will make mistakes, step out of line and constantly test the boundaries, but as a coach you have to pull them up on it, remind them of the principle agreement between coach and athlete. Therefore you have to make sure there is an agreement in the first place and get them on board with you, rather than going down the dictatorship route as athletes won’t buy in to that. With an older athlete you can then ask them what do they feel is acceptable and what isn’t, and what they feel would be an appropriate punishment, so you can therefore create your own set of rules, of which though you need to make sure you follow through with, which some coaches don’t have the ability to do. I’m able to do that as I have quite a military style, and those that test the boundaries with me personally find out quite quickly that they won’t get very far. Not saying I create a military environment that isn’t fun, but I personally start quite strict, and as time goes on and the athlete starts to understand the process then I start to relax.

- What would you say would be there most significant change of approach towards dealing with athletes of a young age e.g. under 11s, to training those that are older with a competitive goal in mind?

In terms of their behaviour you’re going to have boundaries regardless of what category you’re dealing with, but you respect that fact that a six year old kid that turns up to a session once a week because their parent has sent them there, is going to have a different attitude to those who may be playing full time tennis at 16 and wants to be world number 1, so you have to manage the expectations differently, and match the behaviours you expect with the end goal. In the beginning it has to be all about having fun!!! As things progress along in to elite performance the expectations change. When the goal and behaviours are incongruent, you’ve got to call them up on it and say ‘ if we’re aiming for you to be number one, that behaviour is not congruent with that goal, and you won’t get anywhere soon if it continues’. You still have to make sure the session is fun, regardless of what standard or level you’re working with, as that’s the reason they got into the sport in the first place. Goals and expectations can always change, and you’ve got to be flexible with the athlete, and from time to time pull them aside the discuss issues i.e. what they want out of it, and what their expectations of themselves are.

- During a session, would you say you have a more hands on approach to coaching, or would you take a step back and analyse from afar before implementing change? How often/little would you step in?

Something I would say I’m still guilty of even now, is jumping in and having your own agenda about what you want to coach on the session plan and end up not coaching what you see but coaching what’s on the paper. But you still need to have a proper process that involves an evaluation that takes place in a live situation, when evaluating their movement, rather than going straight into a technical drill, and saying ‘this is how you do it, copy this’, you need to step back and see how they move naturally when they’re not consciously thinking about the activity, from which you can then plan on what to do next. The next step is to lay out the objective of the session, and use the evaluation feedback to dictate the plan that is dependent on who you’re coaching. With a younger athlete you take on more of the dictator type role, and say ‘this is what you’re doing’. With a more experienced athlete it will involve more consultation with the athlete and ask them what they think they should be working on now. After you and the athlete know ‘what’ they are doing, the next important thing is the ‘why’ they are doing it, something a lot of coaches miss out on, but important so the athletes buy into it. The session will depend on what stage the athlete is it, so typically with young athletes that may be learning a skill for the first time, more teaching and demonstrating will take place (Mageau & Vallerand, 2003). With a more developed and experience individual, you would put that skill into performance pressure where there’s something at stake, although in any lesson you want to be teaching, training and performing.

- In terms of the relationship between coach and athlete, how would you go about ensuring that they continue to respect and trust you, to ensure that their development continues?

Assuming you get the athletes to respect you in the first place, it is also vitally important that they trust you over a period of time. The biggest thing in ensuring that they continue to trust you is that they can see you’re helping them get results, because ultimately in the field of sport, people are judged on whether they win or lose more.

The athlete has to feel that the things you’re asking them to do are ultimately helping them get better and win more. When you may start getting issues with trust and respect is when they’re not winning, sometimes in situations that may be out of your control, as it’s up to them to deliver the outcomes, but they will still question the processes if they’re not seeing improvement. For long term, knowledge is vital, as you have to know what world class looks like and know where the athlete is currently, and where they have to get to. If you don’t know what world class is in that particular period, you’re not going to be able to help that person reach that level, and therefore can end up losing their trust.

- Over the course of your career have you adapted the way in which you interact with your athletes, maybe due to the changes in society, and the way athletes behave nowadays?

My personality and the way I set up the environment hasn’t changed, as I’ve always been quite a strict, no nonsense coach that has very clear boundaries from day one. I’ve never been known as a kind of joker that tries to entertain through humour, and have always been known as quite a serious coach. I would say my anxiety levels have dropped significantly because I’m now more likely to adapt sessions on the fly because of the experiences that I’ve had, so I’m much more confident in knowing that if something I’m doing is not working, then there’s another 5 options that I can revert to. A former Head of British Swimming coach called Bill Sweetenham always said that in the beginning of your coaching life you relie heavily on the session plan and you only know one way of doing something, and if it goes wrong you don’t really know what to do. By the time you get to the twilight of your career, you find there are numerous possibilities by which you can get the same result. So overall my style hasn’t changed, but my adaptability has to give me numerous options to work with (Sproule, 2009).

- Generally how would you deal with the situation of which the athlete is clearly showing signs of a lack of interest/focus and motivation, and does your approach on this change depending on the individual i.e. do you make use of any punishments?

In my opinion there are 2 scenarios when coaching, one where you don’t get a choice in who you work with, and the other is where you get to pick and choose, which ideally is a great position for a coach to be in. Now I am in a position where I get to select who I work with, and I can say to the athlete that if they want to work with me then these are the benchmarks and standards that I expect in the session, if you’re happy to commit to those levels then you can work with me. The minute they aren’t able to maintain that level you can may be give them 1 opportunity and say maybe this isn’t going to work. Some coaches don’t get that luxury of turning down work, and in some cases may decide to take the money rather than take the moral high ground. Those that may not have the choice because they’re contracted to provide a service for a club or school and who have a mixed group, inevitably you’re going to have a group of people that want to be there, and those that don’t. There are couple of ways you can deal with this depending on the support of the team you’re working with. If it’s an inclusive session where everyone has to be involved its more difficult, but you can have a strike system where you can say if they do something out of line once you get a warning, do it again you’re out for a few minutes, 3 times then you’re out of the session, and in doing so you can potentially create an environment of excellence by saying that people that don’t want to do it and are going to mess around are out. However most of the time it’s very difficult and won’t be well received unless people support your vision of excellence.

Sometimes in an attempt to keep everyone involved, with those that aren’t necessarily motivated you can use pace and lead. You can’t get frustrated as a coach, or have this unrealistic expectation that they should be here, they should be working harder, as they’re not at that point in their life or career to have that level of expectation as they don’t want to be there at that moment. Therefore you have to stay positive with them, find the greatness in them and have different expectation to those that want to be there. For some just turning up in their kit could be a success, of which you could praise. It’s easy to be strict and hard on them as you may feel you already expect them to do such things, but in my experience people respond better if someone notices something that they’ve done well. Don’t try to go at your pace, go at their pace, and if they’re not as motivated to be there, don’t push it, but ease them onto the next step and identify what is progress for that individual. As I work in performance, not development, we don’t have any dead wood in our programme. If someone wants to pay for performance based sessions and they don’t come to the party, then they get a reasonable time to shape up. However if they start slowing the rest of the group down then they’re out, because they’ve already been notified of the agreement.

- Can you recall a moment in your career in which you felt you made a significantly positive impact on the athlete, not just in a sporting sense, but in terms of developing the person?

I can’t single out one particular person, however in terms of developing them as a person it is really important to me and is a big part of my philosophy. It’s well acknowledged in sport psychology literature, mindfulness, purposefulness etc. that it’s not just about developing the athlete, it’s about developing the person. I see my job as a coach, and differentiate myself from a trainer, who predominantly motivates a person to get more energy out of them or teacher whom predominantly help people learn a skill. A performance coach is someone that can truly have an impact on the person as well as the athlete. The general thrill you have of seeing someone come into your programme who may lack confidence or self-esteem or who is unsure of what they want to do in life, and you see them graduate from a programme like this, go onto university, graduate with a degree, and end up doing great things within the industry and business, is personally as equally rewarding to me as maybe working with a junior or senior world number 1 who wins titles.