The Travelling Strength Coach

This week’s guest blog comes from APA coach Fabrizio Gargiulo. As the Easter weekend is upon us many of APA’s athletes will be on the road competing so this post will cover some of Fab’s thoughts on the role of the S&C coach during this time.

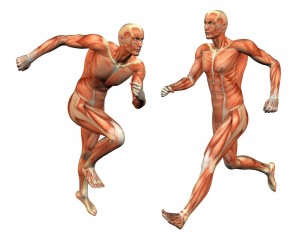

The world of professional (and at some levels amateur) sport often requires large amounts of travelling to and from competitions. I have experienced this since I began working in strength and conditioning and have learnt a great deal from the various sports I have travelled with. My first experiences came working with Luton Town FC, who were at the time in League 1 (English 3rd division), this meant that the team would often have 2 games per week, sometimes as many as 5 matches in 15 days. This presents several problems for the S&C coach. Firstly the logistics of time spent travelling to and from venues, over sometimes vastly long distances. This undoubtedly makes players tired, uncomfortable and often stiff from being seated for long periods. The role of the S&C coach then changes to promoting optimal state of readiness before competition and then maximum recovery possible post-match. The S&C coach takes on the role of nutritionist, water boy, teacher, masseuse and sometimes psychologist or agony aunt to listen to players debrief after their performances. From my experiences in football the S&C coach can sometimes have to defend the players against the manager, for example after a loss, if the manager thinks the players didn’t put enough effort into running or chasing the ball he may wish to punish them with extra running the next day or even immediately. As an S&C coach it is your responsibility to decide how this will affect the players both physically through recovery and mentally, but also to consider the impact of learning from negative consequences that the manage wishes to employ (please see my previous blog about gaining positive outcomes through negative consequences by following this link

This is an example of managing a group or individual player through a season of competitive matches, travelling all across a country and competing in various competitions, some of which will have greater importance and this again is a factor for the S&C coach to consider when planning training for the players to bring them to optimal state of readiness. Sometimes it may be of greater value to the long term goals if an athlete is not at optimal readiness because they are training to achieve a peak in performance later down the line.

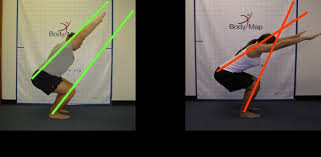

More recently I have worked with a professional tennis player during a tournament block lasting 3 weeks. This presents a different situation to the S&C coach. Being abroad you are in unfamiliar circumstances, you may have a language barrier; you may or may not have access to a gym, equipment or space. In tennis, players typically play daily (if they continue winning) throughout a tournament, with the occasional day off due to scheduling. Ultimately your role as an S&C coach doesn’t change – optimal preparation and recovery – however when you are in a tournament block you need to work backwards from your competitive start date and this means that you can do some training (maintenance) to keep fitness and strength levels up when they are not competing. For example player A starts playing matches on Saturday, he arrives in the country Thursday lunchtime, this gives you approximately 36 hours where you can do some work, the initial goals will be to get the player ready, this may involve a recovery run, a light weights sessions, massage, flexibility or a more intense low volume session to get up to match speed quickly. Player A then wins his match so plays Sunday, S&C coach must help him recover and be ready for Sunday. Player A continues to win until Tuesday, he now has 3 days until his next tournament starts again, the S&C coach must make a call on whether the player should have a rest day, recovery day or training day. Likely also that player A continues winning his matches and ends up in the final on Friday, win or lose he will play again the following day in the next tournament, during that week the player will not train and only focus on recovery, the intensity of match play will be enough to maintain fitness for a while, however over a prolonged period fitness and strength in particular will begin to diminish, thus at some point the S&C coach may have to place the player back into some training and out of the competition block. Typically in tennis players are able to compete in 2-6 week’s worth of tournaments before returning to a 1-3 week training block. A major part of being an S&C coach is the ability to think on the job and to have multiple plans to use dependent upon the situation. There are some great pieces of portable equipment available to use to help out with this, things like; TRX, resistance bands, water filled balls and good old fashioned knowledge of body weight training and utilising what you have in your surroundings – squats with your suitcase, step ups on hotel chairs, pull ups on a tree or climbing frame, stair runs etc can all be integrated into keeping your player fresh and focussed and is often a good change up to the usual training they do in the gym on the track, pitch or court.

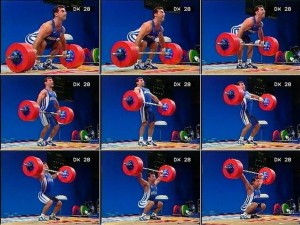

Finally from an athletes’ perspective I have been a competitor at several important matches and tournaments all across Europe. From travelling 24 hours on a bus for a single match or getting a 6am flight to play an afternoon kick off and then fly home all in the same day to taking part in 10-12 day tournaments with 3 international matches in 6 days, as an athlete you often don’t know what to expect or how it is going to feel until you have experienced it. Single matches present different challenges to tournaments, your physical state is important but if it is not at a true peak, I often found that the mental focus was more important than getting 8 hours sleep the night before, of course if you are smart you will make sure you are rested up before taking the trip, but sometimes it is unavoidable when you’ve done 20+ hours of travelling it’s knackering full stop. Good nutrition and hydration especially I found to have a big influence above sleep and travel. Recovery is often compromised also, but it depends how much time you have until you compete next as to how much of an influence this can have – if you have a week, it just means your recovery will be delayed and take longer to restore full state of readiness. If however you are in a tournament with multiple games in a short space of time, recovery becomes very important. A recent experience away with the GB Lions American football team at the Group B European championships in Milan showed how important recovery was. Acting as team S&C coach also, I used my experience to put a schedule together with the coaches and physiotherapists for what training would be done and when etc and they worked tirelessly to prepare us for games and give us the best possible chances for recovery, storing up ice to allow us to have ice baths, taking care of supplements for post game and giving us time to sleep as we played late night kick offs, meaning we finished around midnight and returned to the hotel and by the time we had eaten, stretched and ice bathed it was nearly 2am before we got to sleep, often with bumps and bruises that needed extra attention. I had been at a previous tournament with the GB Lions (before I had studied recovery strategies and was not yet an S&C coach) and we had not been instructed on how best to recover, but were more left to our own devises, albeit with good facilities such as a swimming pool to cool down in and stretch. We played in hot conditions and had trained pretty hard in the 4 days before playing our first match, whereas in Milan we did a single 60 minute body weight circuit session on the first day we arrived just to stimulate some blood flow and get a little bit of match tempo readiness in the players. We then had around 40 hours before we played and only did some core and stretching for the next 2 mornings. From my perspective, I felt better playing in Milan than I had previously, part of this was down to my state of readiness.

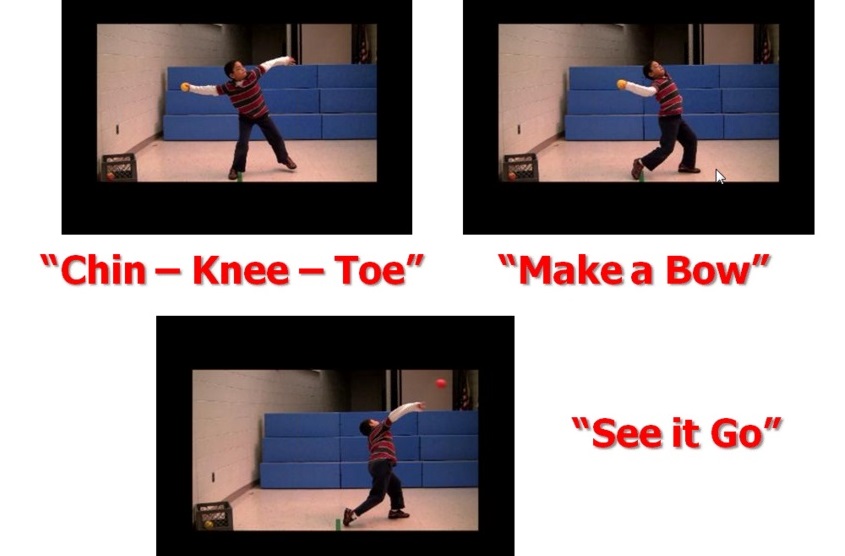

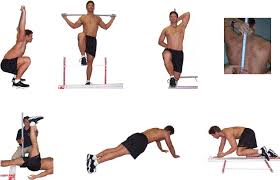

On the first day we arrived the team went through a basic body weight circuit consisting of some low level plyometrics, body weight strength exercises and a core workout plus an extended stretch period. The core and stretch became our daily routine once the tournament started, but as the S&C coach, I felt it was important that the players all experienced a workout in the heat of Italy as this would be a factor to consider when we played. Here is a quick video of the workout we did…

One point that is often over looked for athletes who have to travel and stay abroad for long periods of time is the boredom that comes with waiting to perform. Often you can’t and don’t want to go anywhere to save energy, it becomes important to do things with fellow players that relieve the boredom, in am team environment this is often easy as you are with like-minded people more often than not that you already know. Games, pranks, banter are really important, talking to people outside of the team and about anything other than your sport is often also very useful. Again if there is an S&C coach with the player(s) they may decide that the best thing to do for recovery is get away from the sport, do some shopping, sightseeing, water park or zoo etc. Players will likely also be out of their normal routine, so knowing this and integrating some of it back into their day can also be really beneficial, this may just be a morning run on the beach, playing video games etc. Whilst in Milan we had a day off after our semi final, where we were given freedom to do as we pleased for a few hours before team meetings in the evening, players visited the city, shopped and some of us went to a nice health club to throw a few weights around (nothing more than beach weights to boost the ego), relax in the many spa rooms and pools and eat out away from the hotel, it helped motivate us for our final game after losing our semi-final. I feel it is also important as an S&C coach when away with players to have some time removed from coaching to release some stress and keep you motivated for the long days working with sometimes difficult players and or situations.

The S&C coach has to be an archer with many strings to his bow and be able to travel with flexibility.

If you liked this article please share it, like us on Facebook, or leave a comment!! Remember, the next APA Workshop is on May 24th ‘Speed, Agility & Quickness Training for Sports,’ click HERE to book.

Finally don’t forget APA are running without question the best value S&C qualification in the UK right now!! For more details click HERE!