Speed, Agility & Quickness for Sports Workshop Review- Part 2

If you missed Part 1 read it here. In Part 1 I gave a summary of the 1 hour presentation I gave to a group of 14 coaches, where I discussed the underlying qualities we should be looking to develop in our athletes which will go a long way to developing overall athleticism.

In this blog I will focus on the practical elements we covered. I found it a very challenging but equally rewarding experience trying to get across a whole training philosophy in 2 hours but feedback was positive and hopefully the audience took away the key points which I will summarise below

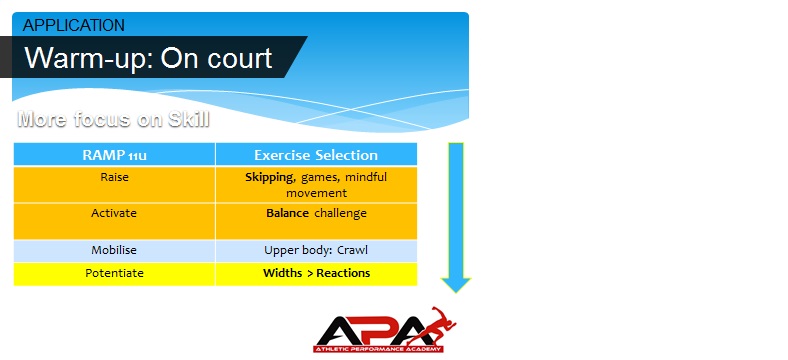

Warm-up

We wrapped up the presentation by bringing together all the previous biomotor abilities into a warm-up method. By doing a comprehensive warm-up you can prepare your body and mind for your speed session and at the same time put some extra work into developing your suppleness and your skills of balance, coordination and reaction speed.

We looked at different exercises we could use to develop these abilities including using a skipping rope, bands around the thighs for hip work, crawling patterns as well as performing locomotive tasks across the ‘width’ of the court to develop coordination. After the warm-up we were now ready to get Fast and do some speed work!

Kinematics

Do you have a picture in your head of what that perfect movement should look like?

Again Kudos goes to Duncan French who reminded me that while we can’t always have an instance impact on a lot of the qualities such as Strength and Rate of Force development that cause motion (these require training), there are still aspects of movement we can improve simply by coaching the athlete into a better position. Asking an athlete to get lower -centre of gravity (COG) or wider- base of support (BOS) is something they might be able to be cued on without them having got stronger. They just became more aware. So a lot of importance should be put on coaching athletes into correct positions NOT just motivating athletes.

Again Kudos goes to Duncan French who reminded me that while we can’t always have an instance impact on a lot of the qualities such as Strength and Rate of Force development that cause motion (these require training), there are still aspects of movement we can improve simply by coaching the athlete into a better position. Asking an athlete to get lower -centre of gravity (COG) or wider- base of support (BOS) is something they might be able to be cued on without them having got stronger. They just became more aware. So a lot of importance should be put on coaching athletes into correct positions NOT just motivating athletes.

Coach it- don’t just motivate it!

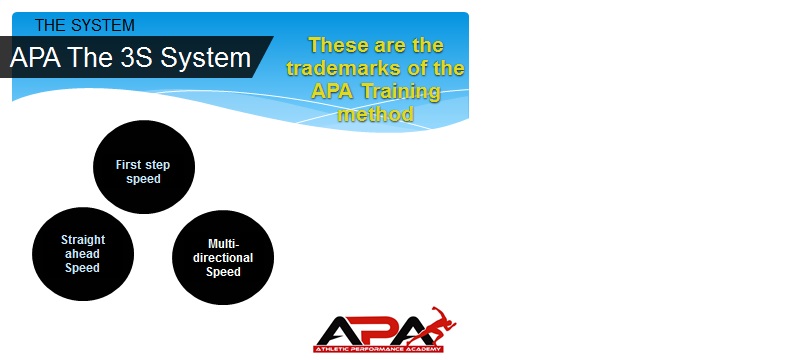

Now they were ready to learn about the APA Speed Development Training System

The 3S System

I introduced the 3 types of Speed that we focus on at APA described above- namely Straight ahead, First step and Multi-directional Speed. We also talked about Footwork which for simplicity I refer to as a specific type of multi-directional speed in tennis.

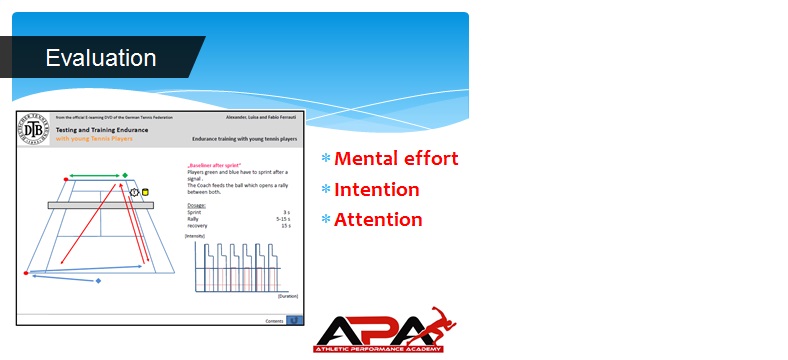

Importance of the Evaluation

Then the first thing I wanted to remind the coaches of was the importance of a good evaluation before getting into whatever drills you plan on doing. This can be a formal ‘fitness test’ at the start of a new working relationship but should also be part of an on-going training process of constant evaluation of the athlete. In any given task I said they needed to know what the outcome was and what the process was to achieve it. The outcome is your ‘Final Skill’ and when it comes to speed it can be associated with a clearly defined timed measure of success such as running 20 metres in under 3.00-seconds or a pro agility 5-10-5 shuttle in under 4.5 seconds. But remember we are playing sport so in tennis it could be feeding a ball so it lands in a certain area of the court and expecting your athlete to be able to hit it back!

Straight ahead Speed

We started off with looking at the Target mechanics of Straight Ahead Speed. I suggested that for tennis I typically encourage all athletes to do at least some work to develop basic sprinting technique but it has increasingly less importance as the athlete begins to specialise in Tennis since there is no reaction to a visual stimulus. Apart from the reaction to the starting gun it is a very closed skill.

We started by discussing how you could evaluate Straight ahead Speed (SAS). I said there needed to be an outcome so in this case that might be time based- sprint 5m in under 1.00 second (acceleration) and 20m in under 3.00-seconds (more top speed). The process could be to sprint the first 10Y in 6 steps with a positive shin angle and 45 degree forward lean at the point of contact of the foot with the ground on the first step.

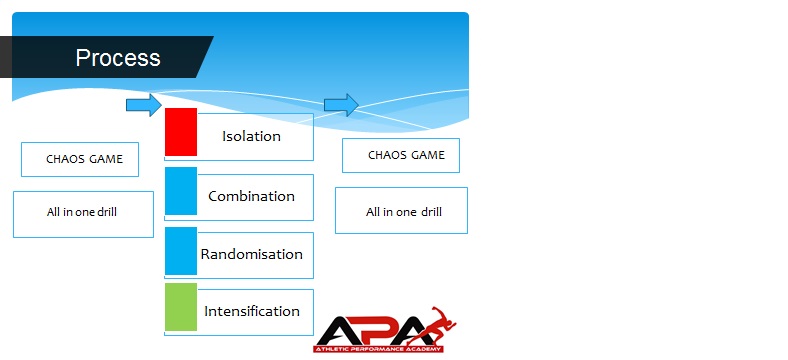

I then discussed my drills progression from simple to complex

I typically observe and EVALUATE performance FIRST using a chaos situation where the movement is being evaluated in an open environment. This can be a sports related game (such as a relay race in the context of SAS) or a drill which involves multiple speed qualities such as an obstacle course so that the qualities have to be applied under a bit of added challenge.

Then depending on what I observe I will first cue the athlete to see if they can correct their body position. If they can then I can go into more challenging drills and simply TRAIN that movement with more COMBINATIONS of skills such as a side shuffle into a sprint and reaction to a signal known as RANDOMISATION, or more INTENSIFICATION by using resistance from a harness or a partner etc.

If they can’t correct it then maybe they lack some other qualities such as suppleness, strength or skill but it’s most likely a combination of all three and simply by putting some constraints in the environment and giving them some good feedback on what they are doing you can correct their positions. This may require that you close the drill down into a simply closed drill with no added pressure- an ISOLATION drill.

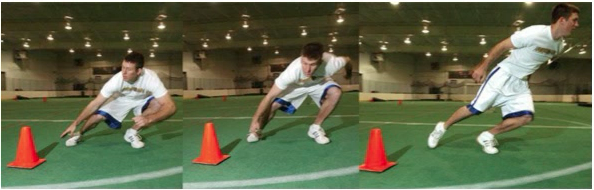

For Straight ahead speed (Acceleration) we looked at the following:

Outcome: 10m sprint in under 1.72-seconds

Process: achieve 10Y (9m) in 6 strides with 45 degree lean and positive shin angle on first step

Drill 1: Isolation- falling start

Drill 2: Combination- fast feet into sprint across court

Drill 3: Intensification- harness pull from a paused forward lean position

For Straight ahead speed (Top Speed) we looked at the following:

Outcome: 20m sprint in under 1.99-seconds

Process: run on balls of feet and lift knees up

Drill 1: Isolation- skipping rope run

Drill 2: Isolation- straight leg shuffle

Then we discussed First step Speed (FSS)

First step Speed and Multi-Directional Speed (MDS)

This is where (wherever possible) it is a great idea to use the tennis coaches to create a realistic open scenario ON THE TENNIS COURT to evaluate the performance. We set up the drill as indicated below so that the person receiving the ball from the coach (Player 1) was working on his first step speed (Lateral) and the opponent receiving the ball from the player on the next shot (Player 2) was working on his Multi-directional speed.

For First step Speed- Lateral (Player 1) we looked at the following:

Outcome: On the court- Get the ball back and make opponent play after receiving a wide ball (just inside baseline) that he has to contact on the full run after shadowed a wide backhand in the other corner

Off the court- Get around a Figure of 8 Cone course 4 times in 10-seconds

Process: run with big powerful drive steps and use a closed pivot step across body on first step

NOTE: We discussed the fact that there are at least 3 ways to move laterally off the mark

1- with open step-jab

2- with closed step- pivot

3- with drop step- gravity

The biggest influences over which one the athlete will use are the width of the base they start with (as it gets wider they move from 1 towards 3), the time they have to move (as there is less time they move from 1 to 3) and whether they start stationary or on the move (if they are stationary less are more likely to use 2 and 3, if they are on the move they will more likely use 1!!!)

Don’t get hung up on this. As long as they are dropping their centre of gravity towards the base of support then everything will work out. If you feel they are not using the step you want then put some constraints in place such as the starting position of their feet or the speed, or height of the ball that they have to catch and the body will solve the problem!!!!

Drill 1: Isolation- Figure 8 cone drill

Drill 2: Combination- side shuffle into lateral sprint to ball catch

Then we discussed First step Speed (FSS) forward and backwards. I said to the coach that there similar debates about this. In Tennis we recognise the principle of Newton’s Law of Opposing Force so in order to go forward they will push directly back using a dig step when we don’t anticipate the forward movement. However, if I know the only direction I will be asked to move is forward then yes, a forward step into the court without pushing back first would make sense. Similarly, to go back we would first push forward slightly into the court before executing our drop step.

We didn’t get time to properly go through an evaluation and process with these but I think all the coaches got the principles.

Finally we had a quick look at Multi-Directional Speed and Footwork. Again, we were a bit rushed to go through a proper evaluation and process but we covered a few basic isolation drills.

We did a tic-tac-toe drill for the footwork required to step out to a ball close to you. I like to encourage stepping out to a ball close to you with an open step. I suppose this makes sense as this is the opposite to sprinting to a wide ball using first step speed and a closed step!

Then we finished looking at some basic drills for Multi-Directional Speed. I said that athletes needed to learn how to maintain an athletic position and got a coach to side shuffle in the service box while palming away tennis balls that I was throwing towards him. I also showed how I used various hurdle combinations to train the basic body positions for learning how to plant and cut.

Hopefully next time I will do a similar format but spend less time on the presentation and spend more time getting stuck into the evaluations and the drills we can do to solve the movement problem.