This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 295 – Jonas Dodoo

Jonas Dodoo

Website

Background:

Jonas Dodoo

Jonas looks after a group of Elite Track and Field Sprinters who have attained success on the Olympic and World stage. He also oversees the Speedworks Charity Program for a fast-evolving Development Group which runs out of the Lee Valley Athletic Centre and is now the Head Coach for a new academy based in the East Midlands.

In addition to this, Jonas has consulted with many many Professional Sports Teams and individual players, including Derby County FC, West Bromwich Albion, Arsenal, Bath RFU, Northampton Saints, Wasps Academy, and Rugby 7’s.

Discussion topics:

Tell us a little bit more about your background and education

”I grew up playing sport, lots of different sport. Was always explosive and elastic, but couldn’t stay in one piece. I’ve got terrible feet, terrible ankles, no movement in my toes. But it sent me down a road to learn, to understand. I think originally it was to go and fix myself, which was my biggest driver. And then I got exposed to great coaches, great therapists. And I did my master’s thesis under Dan Pfaff or studied him as my thesis and had an opportunity to do a PhD in sprinting or to go and try and coach someone to at least be a bit faster. And I went down that route.

So I started in rugby, ended up in athletics and during my athletics coaching career I got exposed back into rugby. And then since that point, maybe over the past eight or nine years, I’ve worked with, you know, various individuals in rehab projects. I’ve worked with various teams in short and long-term projects and really the past three years for me, I’ve been based at Loughborough University with my elite squad of sprinters and then used essentially my down days, so 20% of my week, spent either with Derby County, at one point with West Brom and with England rugby in the build up to the World Cup. So those would be my major projects. And alongside that, I run workshops. I do a lot of coach education and a lot of mentoring.

So it’s been an up and down journey, always driven by my hunger and curiosity about how to make people faster. I’ve also been very inquisitive for sports science, very inquisitive, probably because I’ve been surrounded in British Athletics by some great biomechanists and great strength and conditioning coaches. And it’s made me question, did my athletes do well because of me or despite? Did I just choose really good athletes who’ve chosen the right parents, who had good genetics?

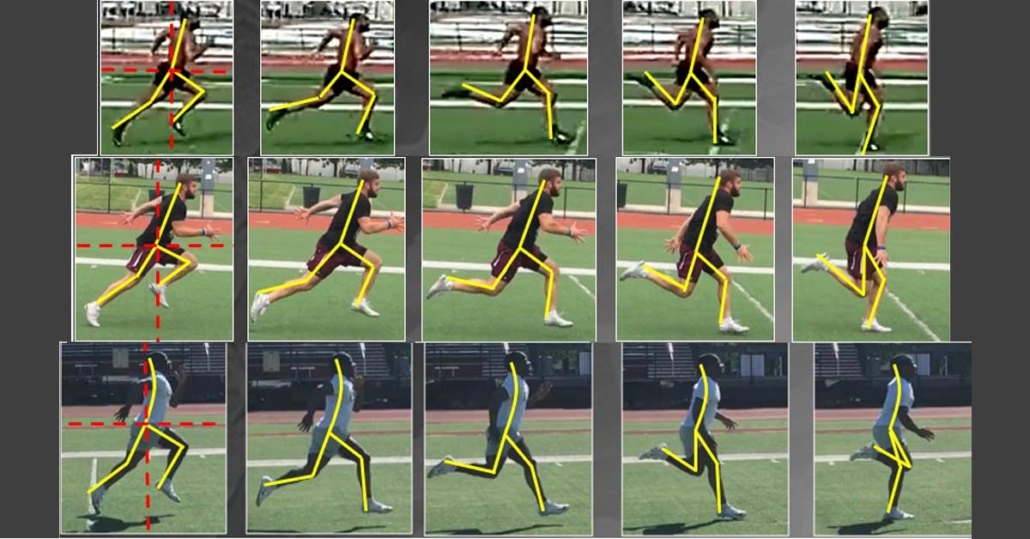

I’ve got this constant need to reflect and ask myself, could that be better? And so it’s driven me down the road to developing for a labour of love, our binary video analysis app. And basically it’s a poor man and dumb man’s dart fish.

Binary Motion Analysis App

The first thing Dan Pfaff pushed us to learn as apprentices is observation skills. He would say, leave the programming to me. Here’s a program, carry on with it. Don’t worry because that could rack your brains for hours and hours a day. Instead, watch movement, watch video, watch from upstairs, watch from downstairs, zoom in, zoom out. And when you’ve got this injury problem, understand what you can do from a movement perspective, from a coaching perspective, how you can create an environment that will distract the athlete from that injury or that pain and redirect their focus towards more effective movement and pain-free strategies.

And so coaching eye was something that was really hammered down very early for me. And by accident, I realized that coaching eye was something that everyone wanted to learn from me.

People come and said, okay, what are the cues, what do you see? And so I’m constantly trying to develop my coaching eye but what we’ve done here with binary is we’ve developed an app that allows you to say rather than have a debate about stride length versus stride frequency, what’s more important. What model, what shape is the priority? Is it this big, long shape? Is it a bit of a smaller shape with more frequency in deceleration mechanics? What’s the priority?

There’s so much debate and lack of consensus in sports science, that if you’re an inquisitive coach, you can easily get lost, easily buy into one side of the argument. I’m saying, take a step back. What’s our priority? Velocity, that’s our priority. And what do we want the shape of velocity to look like? We want it to keep getting faster. If we can find a way to make it get faster really steep and keep it continuing to get faster, we have high acceleration and we have high velocity. We have a good RF and we have a great DRF, right? That’s JB Morin’s language.

Daz comment: (definitions explained)

Ratio of Force (RF)– is a ratio of the step-averaged horizontal component of the Ground Reaction Force (GRF) to the corresponding resultant force.

Index of Force Application Technique (DFR)- expresses the athlete’s ability to maintain a net horizontal force production despite increasing velocity throughout accelerated sprinting.

In practical terms RF reflects the ability to project a large amount of your force in the direction you want to go

In practical terms DFR reflects the distance over which athletes are able to accelerate (i.e., distance to peak velocity).

The reality is what binary does for us is it helps us take a step back from our bias and go based on what we’re seeing, what’s happening with the data, what’s really happening. And in elite settings, people have Lasers and speed guns and video analysis, 3D analysis, Opto jump. People have got these tools, 1080, great tool. Dyno speed, very similar tool. They’ve all got these tools that give you some of the information or all of the information. And all I’ve been trying to do is go, okay, this is what I’ve experienced. This has helped me in my journey. How do I simplify it, distill it and make it available to anyone that has an Apple device? Yeah, at least to a more recent one, iPhone 5 not good. Yeah, but I have an iPhone 7, it records at 200 frames per second, it does the job.

My expectations are probably based on my bias. This is what I think good movement looks like and fast speed looks like. And I think over the past five years I’ve been able to take a step back from my bias or at least combine my bias with reality, with real data, with real numbers and actually maybe close the line between what I perceived them to be able to do and what they actually do. A long winded way of describing it.”

Can you tell us more about your reflection process

”So I guess during my degree and doing my masters in coaching science it really wasn’t about the science of sports science or anything like that, but really more about psychology. For me, my learning through my masters specifically, learning from great people I always noticed that no matter what they did, they look back and say, ”it could be better or where could it be better, at least?” They asked that question. So when I think about reflection, I think about reflection in action. You know, some people say I’m a great scrambler, no matter what the session plan is, I’m rarely scared or even intimidated about changing the plan on the go within the set, yeah, within the minute. If I see something and I think it can be better, I’ll make the change within reason. And so there’s this reflection in action and I think I can only do that because I’ve been coaching for so long and I’ve coached so many different types of people and I’ve made enough mistakes and I’ve had enough regret for making those mistakes that it really influences my decision making.

And there’s reflection on action, like reflection in hindsight. My wife was an Olympia, my wife was an elite coach, has coached to really high level and in multi events, in long jump and she was probably the biggest influencer on my coaching philosophy and specifically around training design, session design. And she is an important reflective, almost mirror for me. She knows what to say, when to say it. She really knows what not to say. That’s probably her gift.

That’s what I’ve learned from her, is that I give too much information. I’m too honest sometimes. And I’m not just too honest, I’m also a bit black and white. So like I’m a bit too direct sometimes. I’m a bit too frank and she’s almost the opposite. Reflection for me is a big deal because the better we can reflect, the better we can accelerate our development. And I think maybe that’s always been my issue is that I’m in a rush and not a bad rush, but I don’t like wasting time. I like being efficient with time. So if to apply that to my own philosophy as a coach, it means that whatever I can learn in a year, the question is, can I learn that in six months.

Now, a great coach Mike Afilaka says ”you can’t microwave experience’‘. And it’s true, yeah. Even if you learn every single thing on speed in Wikipedia, everything to do with speed right now over this six weeks, seven weeks of COVID, does that make you a better coach? Actually, you might get worse because you’ve now got more information, you don’t know what to do with it, you know all these new rules, but you don’t know how to apply it into your environment. Some of them seem like they contradict what you’re already thinking. And you now have to practice and make sure that will balance up within like a training scheme.”

In terms of developing your business and having a business head on as well as a coaches head, how difficult has that been?

”That’s been really tough. I’ve always believed coaching should be selfless because athletes generally are selfish, and we need that balance. And so I’ve done that, but people see the website, people see the successes, the consultancies, the athletes’ performances, but they don’t see my bank account. And they don’t see the fact that I spend 80% of my time on the track, but track only brings in 20% of our household income. So I spend all my time chasing consultancies, doing extra work, work until midnight, just so I can coach. That’s the luxury of being an elite coach. Most of us are doing other work or just coaching track and field in general, most people do other work and the passion of the sport is driving them to the track on a daily basis.

That was fine when I was young and dumb and single and no kids. And then I had Logan, so that was five and a half years ago and actually that was all right. But even then that there was a sign. I was burning myself out. From that point I noticed that the stress and pressure of being a dad and being the main source of income and also being a lead coach in an elite group, where I am their dad as well and trying to run a business or at least keep everything in balance was too difficult.

In my experience, the way I invest my energy into my coaching and to my athletes, I’ve realized that my family, my kids needed that energy as well. And so when I was giving that energy to both parties, I was burning the candle from both ends. So the small things that we’ve done, moving to Loughborough because I was working in Derby County and it was all close, it was real easy. My athletes, all of my consultants had been in one place at least for a year or two made sense. It was very well balanced. Then I started working for England RFU. So I’m driving back down to London now and even further than London, I’m driving down to Berkshire.

The balance for me has been very difficult and I’m in debt as a result. And would I go back and change it? I really don’t know because also I got to be completely in the deep end, in the deepest ocean of coaching and I’ve been experienced and exposed to amazing opportunities, amazing players and athletes and systems and coaches. , Everyone says high performance sport is not healthy for the athletes, their bodies, for us and our emotional energy and all of those things.

I see many, many coaches who really shoot up to the top of, let’s say of whatever it is. Yeah, they’ve got really high status who follow managers around, maybe where managers are going from club to club or follow athletes around when they’re going from country to country, when they’re relocating who’ve had two marriages, who don’t have kids that really liked them, who have lots of money in their account. But when they go home and sit down and really look around, they, you know, they’ve maybe sacrificed their family for their career. And I was very happy to sacrifice myself for my own energy, my own social time for my career and that’s paid off, but I’m not happy to sacrifice my family for my career. And that’s been an important turning point for me.

If during the most stressful times you don’t feel you can carry on committing to what you’re doing, then you shouldn’t take it on because that’s what you need to be prepared for. When things go smoothly, that’s the easy time. The hardest, most challenging and sometimes the most exciting time is when everything’s going wrong, because that makes you have to adapt. You either adapt or you die. And if you don’t have that adaptive energy, because you’re spending it with your family, then the coaching dies. If you don’t have that energy for your family, because you’re spending it with your athletes, then your family dies essentially. And so the reality is finding that balance has been really important for me. Knowing my worth has been important for me. Showing my work in my unique way, I’m dyslexic. I like to read, but even just yesterday, I did a tweet, spelling mistakes everywhere. So I’m not going to be writing the most informative blogs. But I know my topic, I know my subject, I know coaching, I know people, I have emotional intelligence and I like to summarize and simplify things.

So finding my business side has been difficult because not many people do things the way I do it. And so I didn’t have a model or template to copy. But actually my business and mentoring and consultancy and stuff has happened by accident more than on purpose. People come to me and have come to me and asked me more and more questions, it’s made me go, oh, you’re an expert or you’re an elite person and you’re asking me this question that I think is fundamental. That’s my bias. It’s fundamental to me, but it might not be to you. Maybe there’s a product there. Maybe I can replicate that and share that with more people. Do you think more people be interested? So I’ve gone into business almost not by looking for a product and trying to sell it. I’ve almost been just people come in to take this product and I’ve gone, I should repackage that and make that available for other people.”

It’s what you’re doing already that you’re just modifying and tweaking to make a business out of it. And that’s not a businessman talking, that’s a coach talking to make a business. I think that’s really interesting to me.

”For me, it’s love, like I know that if I love something and I might love it because it’s interesting ‘cause it’s a puzzle. I like puzzles, because it’s challenging and forcing me to be outside my comfort zone. But if you love something generally when you’re tired or when you’re pissed off it, you don’t give up. Yeah, and maybe it makes you work harder. And you take a step back from it, maybe you sleep on it and actually you have some deep reflections and you’re better, right. So for me, it’s always been about the love. If I love a topic, if I love a subject, then I’m going to , generally, I’m going to be good at it and I’m going to understand it.

And through that understanding I’m going to pull it apart, like a video machine. I’m going to open it up and look at all the parts and I’m going to put it back together and I’m going to summarize it really simply. And that’s how I like to just live in my world. And it just happens that that’s how people enjoy learning on deep topics. They just want to know to heuristics. They just want to know the rules are and the KPI’s. You know, it’s one thing to know the rules, but if you need to apply those rules in your setting and break those rules, do you just need to know the rules before you break the rules or do you need to know these broken rules too?

So it’s one thing to know basic mechanics and another thing to know what can I do right now, next week to make my players better, to make me better as a coach.”

Let’s talk acceleration principles, what are the principles that you live by when it comes to acceleration?

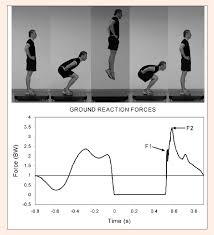

”If we’re just talking about the basics of acceleration, the goal is to get from A to B. So if we took a hundred metres, the goal is to get from zero to a hundred as fast as possible. And obviously we can break that into phases. And when we’re speaking more specifically about initial acceleration, obviously we can in team sports and even in track and field, we can measure a 10 metre time, right? Five metre or a 10 metre time is traditionally used to get an understanding of someone’s ability to accelerate.

But many of my clients and many teams will put down timing gates. You know, if they want to do speed training at their club, they believe that if they put down timing gates and they drive intent, this is an important thing, a lot of people talk about that sometimes the biggest priority in speed training is just getting the players to try hard and actually intent, high intensity in the effort and the speed and the timing gates can help that then they give them a time.

If your goal is your 10 metre time only, then you might be missing a trick because I can run to 10 and you can run to 10 in the same time but I might be at a higher velocity than you.

And all that means is we’ve got to 10 metres at the same time, maybe you’ve been a drag car and you’ve got there by really your first four steps going and then actually your rate of acceleration drops off. So you did most of your work in the front side of the race. And maybe I’m still a drag car, but I’ve got a tiny bit less horsepower, but maybe I’ve got less drag too. Like literally I’ve got less air resistance and so I might get to five metres in 1.0, let’s say you get there 0.90 but we still both get to 10 metres at 1.7. I’m accelerating still. You give me three more steps I’m in front of maybe even one more step I’m in front of you.

So when we talk about acceleration, we’ve got to be careful that we’re not setting a goal over a 10 metre time and encouraging a technique and a strategy that gets us there fast, but puts us in a bad position.

And then you think rugby, you think, okay why does it matter? If my aim is to get to the 10 metres, if my aim is to get to my defender or my attacker as quick as possible, and that 10 metres is in front of me, I just need to be there as quick as possible. But actually you look at, you know, you listen to someone like Frans Bosch or John Pryor or Dean Benson and Eddie Jones, they talk a lot about options positions, right? You need to be able to get to 10 fast, but be in a position where you can organize your body to make a decision. And that position is often in a position where you can remain reactive with your feet and you still have control of your center of mass. You’re not over rotating. You’re in a position with your pelvis and your trunk where you can rotate and you can do other actions where you can scan if you need to, and then use your upper body if you need to, while still using your legs to push you to go faster.

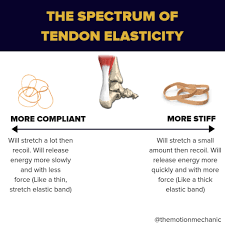

And that position is an efficient position. The reality is by the time I get to 10 metres, I need to be in an efficient position to make a decision in team sports. And I also need to be an efficient position to keep getting faster in a linear sport. So for me, efficient acceleration, no matter where we’re at looks the same. You maintain a frequency and a stiffness that allows you to be energy efficient, but also be in a position to make choices and make decisions. So that would be my first start of acceleration. I haven’t talked about postures. I haven’t talked about shapes. I haven’t talked about what the fundamentals of athletics in 100 metres versus hurdles versus maybe long jump, that’s all a secondary discussion.

Can you produce the right forces and throw yourself where you need to go? That’s again, JB and RF, yeah. What ratio of your forces are you directing forwards? That’s how effective you are and you can be really effective without being efficient. We can both run a 1.70 and we could say 1.70 is the time that we need in our sport, but I might do it in a way that really allows me to one, save energy, two, be in a position to make a decision or three, be in a position to keep getting faster. That might take more stress off of my lower limb and that might just give me a bit of an energy reserve that I can use better to continue going for repetitive actions in the game.”

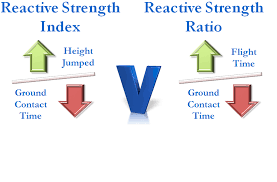

Coaches are often deciding which metrics such as stride length, stride frequency to focus on etc. Do you think there is too much focus on that?

”So I think there’s too much focused on it, yes. I think or I know that the effective and efficient strategies are about the best combination of your spacial temporal characteristics. So your ground contact, air time, step length and if you’re going to look at a drive index or you’re going to look at some kind of way of combining those numbers, that is all about combinations. And neither is it about maximizing your stride length, neither it is about maximizing your stride frequency. It’s about finding this optimal because of the fact that our limbs don’t work in isolation, energy transfers through our pelvis to each limb. So it’s not about getting the most out of the pushing leg and getting a massive toe off distance and making a massive shape because if you do that, what you may end up doing is not having any pretension in your swing leg that’s in front.

So if you really think back to what are the biggest priorities in sprinting or in performance it is one to project yourself towards where you want to go from A to B. And it’s another thing to be prepared for the next step.

Those are the two priorities; project and be prepared. And if you over project you’re under-prepared, and if you’re over-prepared, you’re under projected or you under project.

So we’re always looking for this balance and the great thing about binary is that we’ve got all of the spatial temporal numbers. We’ve got all of the angles and orientation numbers. We’ve got everything, most things that you can get, everything that you can get from motion analysis, we can get, but if you’re only going to go for one thing, I’ll go for velocity or go for acceleration. I’ll go for the reality of the fact that we want to be fast, we want to spike our acceleration and maximize our speed, is those two things. So we care about speed and acceleration. Now, acceleration as a number or power as a number normalized, average, horizontal external power, but let’s just call it power, versus acceleration, they kind of give you a similar thing and the great thing about them is they take into context, the velocity you’re moving at and the rate of change as well.

So those would be metrics that I would hang my hat on because they don’t tell a lie. You can make a perfect shape and if your acceleration is less and your velocity is less, it’s not fast. It’s not what you really want. With that you need to take into account that people develop over time. Sometimes when they learn something new, it slows down and it gets faster. So there is a bit of art behind recognizing what you should hang on to and be patient with and what compliments that exercise.

If that’s a shape you want to do, are you complimenting it with some strategies around training it, creating what capacity, increasing the mechanical properties of that muscle group or that system. If you combine teaching and training, then that new movement pattern is more likely to be successful, but regardless, look at velocity, look at acceleration. Rarely is it something we can look at because we don’t have the tools. We don’t have a 3D Vicon system or a pitch or in your clinic and now we do.”

Is it only experience that can allow you to differentiate what you need to change?

”No. I think for me, pretension and preparation for the step are key things to understand (Daz comment: that perhaps doesn’t rely on extensive experience if you know what to look for). We definitely want to project ourselves where we need to go, and we definitely need to be prepared for the step. I’ve said this before. So no matter what change we make, we have to make sure that there’s an acceptable bandwidth of projection and preparation. So let’s say velocity goes down because we’re working on something and we’ve interrupted the habitual flow of the athlete.

We’ve maybe given a taboo internal cue, but it was necessary for them to make sense of it. That we’ve played with some drills to give them some context and for them to find a feeling so that internal cue is now poo-pooed because now they understand the feeling of it. And then they’re working on it. Sometimes when you understand a feeling of it, but you’re still working on it, you might decrease maybe your velocity. Your rate of force development might reduce a bit, because you want a bit more control.

So velocity it might go down, but you want to see the classic spatial, temporal variables, ground contact time, step length. You want to see rhythm. That’s what you want to see, even if they get a bit slower and even if you’re coaching something within a session, and you’re having undulations really in how well they’re applying the skill, you want to see flow. You want to see a gradual change. You want to see that if you looked at your step length, that every step is getting a bit longer.

If you looked at ground contact time, every ground contact time is reducing. If you’re looking at initial acceleration, you want to see that the ratio of air to ground is changing and that they’re spending less time in the air, more time in the ground in the first step and that this relationship remains at least for your first three to four steps. And then we start to see a break point, which is essentially where they start to spend a bit more time in the air and less time on the ground.

So there are some rhythms that we expect in running smooth flow, like a plane taking off. You want to see a smooth flow. And there are some rhythms that we want to see in velocity, velocity, gradually getting faster. And once you understand those rhythms and we want to stick to those rhythms, we understand that there are also rhythms in all of the other characteristics. Gradual change really is the name of the game and John Keily, and I think maybe Craig Pickering had a paper on smoothness, and it’s the best paper ever for me. I love John Keily’s work because it’s just a great summary of what we want in our data.

We talk about smoothness and we know what smooth, silky movement might look like or smell like or sound like, but we don’t know what smooth, silky data should look like, smell like or sound like. And actually it’s very similar. It’s very, very similar. You can look at someone’s data and see their step have gradually changing. And suddenly there’s a bad rhythm. You know, suddenly, you know, it was increasing by 10 centimetres each step and then suddenly it increases or decreases by 20 centimetres. There’s something going on. Or it stays the same when it should have been changing. There’s something going on.

So it’s not just experience. I think if you know what to see in good data and good movement, you can figure out and decipher what you see in your environment.”

Can you comment on team sports versus sprinters? How can team sports go about trying to best utilise the 20 minutes warm-up time?

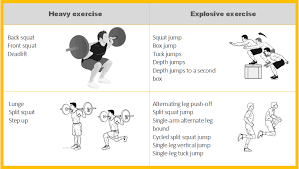

”I think, this is where like I’ve always talked about projection, switching and reactivity. I’ve always said that these are really important umbrella terms that help me make sense of the world. And I think if I was going to focus on acceleration and I wanted to maximize the learning, as well as the mechanical load or development of specific muscle groups, I’d pull a pulley. I’d pull X-Genies, I’ll pull a sled, I’ll do something resisted, right? And a lot of our clients and teams, especially with this new preparation for preseason, have bought 20 X-Genies. And they’ve linked them all to the walls, players can’t share equipment. If they’ve bought 20 X-Genies, they put them all in a wall and they recognize that the resisted running does lots of the teaching for them.

Projection I really think has orientation. ‘Cause when you say projection, we’re not really saying where, which direction you want to project. I feel like if we’re talking about orientation, we’re talking about some of the summaries from one of the resistance running research, which is RF again, keep coming back to it. Are you able to project a large amount of your force in the direction you want to go? Is that large ratio of force going forward, going horizontal? So for me, that’s one of my first priorities, orientation, and I’m going to use resisted running for it. Another priority is range of motion. If you have a relatively large range of motion on the front and the back side of your running cycle, not just the front side, not just the back side, if you have a relatively large range of motion on both sides of the flexing leg and the extending leg, then that tells me two things:

One. It tells me that you’re extending the leg, you’ve pushed your center of mass outside and away from your center of support. So you’ve had a nice extension of your posterior chain. So great. You’ve got a large range of motion in the backside. Two. On the front side, if at the moment of toe off, when you finish extending your knee is relatively high, even in acceleration (so we’re saying your hip angle is maybe closer to 90 degrees than 110 degrees), then clearly during the step, your thigh has punched forwards. But if at the moment of toe off, when you finish extending your front thigh is actually down here, then clearly during the stride, your thigh didn’t come forward quick enough. So at the moment of toe off is a great time to see, okay, what’s happening with extended leg. What’s happening with a thigh in front?

So finding an effective range of motion in your legs during projection and orienting yourself forwards just describes a lot of things, but for a novice coach, if I just want to make sure all the forces go forward, I’ll use a sled. Are they utilizing their range of motion? If not, then why? Is it because they’re not pushing against the ground or is it because they’re not punching their knee forward? And the nice thing about punching your knee forward whilst pushing against the ground is it pushes your center of mass out in front. It makes it easier to orientate your forces forwards.

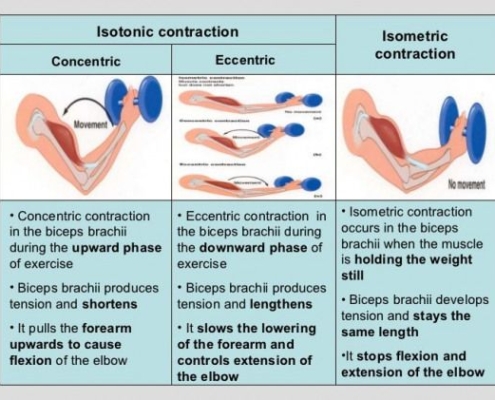

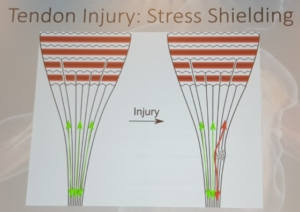

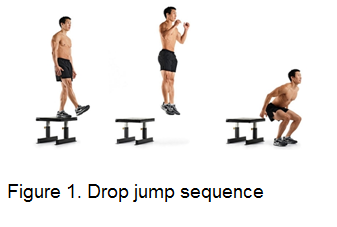

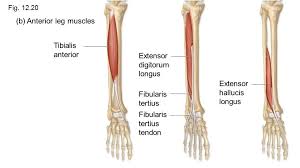

So this RF puzzle that’s the all our real goal is, and can be solved by orientating yourself forwards and separating your limbs really well. So once you’ve done that, that’s the projection part done. That’s the pushing part done. Then you got to be prepared for the next step. So then the question is, once they’ve done these actions, and then they swapped their limbs, does their shin land in a position where it’s stiff, the ankle is stiff, the heel doesn’t drop. (Daz comment: this is the reactivity part). The shin is stiff, is stable and allows the hip to extend early. Or does the shin land vertical, the heel drops, the shin has to roll forwards before the hip can push again. And if you’re in that position, that’s less stiff, that’s less reactive. Do you want some compression, some load before you explode? Yes. As any performance that can have a bigger touchdown distance and during a tiny bit of deceleration on the step and tiny bit of breaking it, they almost use that time to multiply and potentiate extension, right? They’re getting that highest eccentric to then load the concentrate action.

So fine, but there’s a bandwidth. There’s landing too far behind and too stiff and not enough pressure to push and there’s landing too far out in front and almost decelerating too much. So that’s five or six minutes talking about what I would be summarizing for a coach. So I’ll go back to it. If you orientate yourself well and go forward with good range of motion in your legs and then switch your limb so you can be reactive and do it again, then I think nearly all performance can do that. Rugby, football, forwards, backs. There’s a bandwidth to it. Maybe you get a bit less out the back, a bit less out the front. Maybe you’re landing a bit further out in front, a bit further out behind, but I’m talking about centimetres. And, generally the summary is the same for everybody. And so when we look at our teams, well players, if I was in a setting and I had 20 athletes, I would just be getting them to pull heavy things, recognize how to orientate themselves well with a good range of motion. The heavier it is the more horizontal I have to be and actually the better I have to switch because I have no air time.

If more horizontal you are, you don’t have air time. No air time, less time to be prepared. I’ll pull medium things because I still have to orientate myself, but I have a bit more time. I’ll be pulling medium weight because it gives me a bit more velocity. It’s more challenging. I’d be running without any resistance. Same drill, same task and I think that differential loading allows them to explore different strategies to do the same task. So it’s just movement variability. It’s just giving them options. Are we doing resisted running for the physical, mechanical loading, or are we doing it for the teaching and the differential learning and almost creating a constraint for these guys to make sense of the world and, to explore different strategies?

I think we’re doing both. I think on some days we do minimal amounts of runs and we’re really just using resistance running for teaching and potentiation and on other days do large amounts of resisted running done with variability and combined with plyometrics. This would allow us to create a massive work capacity to do anything else when it came to speed work, because it meant that we had lots and lots of contacts, high velocity contacts into the ground conditioning the Achilles, conditioning soleus, conditioning foot position, conditioning knee to be stable, the hip to be the prime mover, really locking in lumbar and just making sure these guys push through their bums and stabilized through their feet. And so when we move to either more pre-planned or more rugby related stuff, the guys just seemed to be able to tolerate it more than usual. Lower limb injuries went away, hamstring stuff minimized, and actually we seemed to see that when we dropped some gym work on a specific day and replaced it more with resisted running, that they didn’t just run faster, run PBs and run fast times and GPS. Their next gym session, they also came in and they seem to be wired.

Yeah. So again, long-winded but I think for me the summary is if we clarify that our goal for all our performers is to orientate large forces forwards with a decent range of motion and to make sure we can be prepared for the next step, then our RF will be good, but our DRF will also be good. That’s easy to coach. That’s easy to do in large squad because you’ve really got two goals; if go forwards when you pull something heavy and you don’t orientate yourself forward, you don’t go anywhere. So it’s great for athletes to feel because when they pull something heavy it can suddenly change something about their synchronization of their limbs or sequence of their movement or spine discipline. Because the priority is really, do you have good spine discipline? Do you have good shin discipline? And the shins would tell you a story about the whole run just by looking at the shins, right.

That’s really easy to teach because if you don’t, if you’re trying to pull something heavy with bad spine discipline and shin discipline, you won’t go anywhere. You just won’t go anywhere. You won’t move anywhere. So the athletes figure it out. And the athlete who don’t figure it out, that’s when you intervene. But if you have tools that teach what you want for you and you just have to provide some feedback, then you can get large changes in acceleration and velocity within large squads. You don’t have to be super coach to make those changes happen.”

Can you finish off by commenting on GAME SPEED, the teaching versus training, and how we ensure transfer from one thing to another?

”I think they’re two different things. Firstly, so ”teaching” and ”training” for me is really down to the fact that just because someone looks pretty doesn’t mean they’re going to actually run fast and then just because they can run fast, it doesn’t mean they’ll do it in a game. So if you want to make sure that technique turns into fast running and physical robustness to do those actions repeatedly, you almost have two tasks there. Can you run fast, great. Can you do that eight times within a eight minute period? Yeah, it’s a different discussion, right? Teaching and training for me is understanding what exercises, what mechanical properties are necessary to run fast.

What does that mean? It means that for me, that if I want to develop someone’s ability to run really, really fast in outright running, I’ve got to make sure they also have the physical tools based on things that I’ve done maybe in the gym with eccentric work, with flywheel work, with isolated versus inter-segmental work. But also I need to probably in team sports, more importantly design running conditioning sessions that develop the technical movements, but under some duress. And you know, everyone’s like if you’re doing speed work and you’re not giving people enough recoveries, then you’re a bad coach. But when you’re training for speed or you’re training speed is two different discussions. If I’m training for speed, I sometimes have incomplete recoveries. When I’m training for speed, I want the movement to look similar, but I also want to create the physical underpinnings, the energy system, the work capacity, the tolerance to essentially mitigate risk when I trained speed.

So that’s a really important concept. Everyone wants to sprint now in sports, but people are now getting more injuries again because they’re doing too much sprinting at the wrong time. They don’t understand phase potentiation. They don’t understand how to drip feed it over time. And when they drip feed it, what else they should be doing on the field with resisted running, with repetitive speed endurance or repeat speed endurance and with your gym work. You do that so that when you need to run really, really fast, you can do it. You can recover from it and it’s got less stress on the body. So movements and muscles or teaching and training, that’s where it comes to.

Game speed is more about once they’re confident and clear and they have repetitiveness, they have the ability to do it almost under fatigue and under some kind of distraction, game speed is more like, can you replicate these movements, high velocity actions whilst being super distracted when you don’t really care about the movement? Where you care only about the outcome. You don’t care as much about thinking about it. You know you need to be in the right position and be there fast but you’ve got a number of distractions. So game speed to me is a big deal. Eddie Jones loves speed work, loves speed training but if it doesn’t finish with some game speed, if it doesn’t look like what they need to know, and if we don’t put them in positions and scenarios and stress test those scenarios for them to be able to run fast and be efficient or and be effective in the skill work, then there is no transfer and he won’t be happy.

I’ve done most of my learning with the great team coaches. Mike Ford, originally at Bath, said it’s great that you do speed work, but firstly, do they stay healthy? Secondly, does it turn into the game? And if is a no to any of those, you failed your task. And so really for team sport coaches, if you do the first stage and you do the right teaching and you underpin it with physical qualities, the likelihood of transfer just increases without even game speed. Yeah, that’s the reality. If your guys have the physical capabilities to repetitively do what you want them to do, and that’s their path of least resistance, that’s probably the most important thing here. That when they’re under stress, that when their body decides I need to get from here to here as soon as possible, the body knows that the most efficient way for me to do is use this movement pattern. That doesn’t happen because they’ve done wickets or pulled the pulley once or twice. That happens because the strongest muscle groups in the most efficient chain for them to use are the ones they choose to use. It’s a chain that you’ve trained. And until it is, then you just have people running fast, running straight lines, running PBs and GPS, great. But then when there’s a break and I have to do a box to box, they completely regress to what is comfortable, what is normal. What is the path of least resistance.

So I think game speed is a complete separate topic. I think game speed, you have to learn and design your game speed from top down. You have to have good skill coaches, good head coaches who are clear about what they want, clear about what their players do or don’t do very well and can teach you. I’ve been taught by some great technical coaches about what they want and I’ve just regressed it, reverse engineered it and gone, oh, that’s just a skips for height. And I was talking about high balls on one of our mentorships the other day about going up for a high ball in rugby and the skill of doing that is just a skip for height. Is really just a skip for height, under lots of pressure on a, maybe an unstable surface because you’re running and jumping but it’s skips for height.

So if you can dissect the perception action from the physical, and you can be clear about the two, you can develop the physical and make sure that they’re clear about the technical as well as have the physical capabilities. And then you put them under more and more stress so that they can connect this new skill under the main skill, then it transfers. Some people, have the perception. So make sure they can perceive it, great. But if they don’t have the wheels or they don’t have the chassis or they don’t have the suspension to do the task, it is great that they make the right decisions, but they’re in a Ford Focus, not in a, I don’t know, Porsche Boxster. I don’t know. I’m not very good with cars. I don’t know why I use this analogy. But hopefully that kind of gives you a flavor of where I would go with things.”

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Coaching eye- one of the most important skills to learn as an apprentice coach is observation skills.

- Step back and remember the goal- What’s our priority? Velocity, that’s our priority. And what do we want the shape of velocity to look like? We want it to keep getting faster.

- Coaching vs Business- they don’t see the fact that I spend 80% of my time on the track, but track only brings in 20% of our household income

- Outcome vs Process- If your goal is your 10 metre time only, then you might be missing a trick because I can run to 10 and you can run to 10 in the same time but I might be at a higher velocity than you.

- Projection and Preparation- biggest priorities in sprinting or in performance it is one to project yourself towards where you want to go from A to B. And it’s another thing to be prepared for the next step

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

Twitter:

@EatSleepTrain_

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 367 Gareth Sandford

Episode 362 Matt Van Dyke

Episode 361 John Wagle

Episode 359 Damien Harper

Episode 348 Keith Barr

Episode 331 Danny Lum

Episode 298 PJ Vazel

Episode 297 Cam Jose

Episode 292 Loren Landow

Episode 286 Stu McMillan

Episode 272 Hakan Anderrson

Episode 227, 55 JB Morin

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 212 Boo Schexnayder

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 204, 64 James Wild

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 183 Derek Hansen

Episode 175 Jason Hettler

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM

=> Follow us on Facebook

=> Follow us on Instagram

=> Follow us on Twitter