The Language of Coaching

With the end of a third lock down in the UK behind us, we haven’t slowed down in our vision to be the Best Tennis S&C Team in the World. We are committed to a weekly CPD session and last week Konrad gave us an exceptional presentation, the content of which we wanted to share with you! We welcome back APA coach Konrad McKenzie with a weekly guest post.

The Language of Coaching

Today, I wanted to talk about a book I read by Nick Winkleman. “The language of Coaching”. This book was great as I wanted to seek ways to “Lean out” coaching cues. This blog will in no way “scratch the surface” of the complexity around topics of attentional focus, skill acquisition and neuroscience. I will highlight areas which I thought were pertinent but I implore you to read the book. The areas I will dive into today will be:

- 3P performance profile

- Motor learning vs Motor Performance

- Coaching and attentional focus

- Analogies, Internal and External cueing

- Constraints based/Tactile cues

The 3P Performance profile

3P performance profile are a series of questions, practitioners would ask when seeking to solve a movement issue. Position, Power and Pattern. Positional questions includes asking whether the subject has the prerequisite mobility and stability to perform the movement. Power is related to the required the strength and power capabilities. Pattern refers to the coordinative and skill acquisition. If you imagine our position and power relate to the car whereas the “Pattern refers to the driver.”

Before I start the blog I want to highlight a few key terms to get us all familiar with motor skill learning:

Motor skill learning refers to an adaptive process whereby short term changes in behaviour can be measured and observed during or immediately after a session.

Acquisition phase– The acquisition phase is the initial period of improvement. It covers the period of time from when the learner is unable to respond correctly without assistance through to when they are able to respond correctly without assistance. This can be broken down further into stages.

Retention Phase- is the Ultimate assessment of motor learning which takes place in the future and athlete is able to demonstrate a skill void of any coaching influence.

Motor learning vs Motor performance

I presented on this topic at work as I felt it was important. But I asked this question to my colleagues,

“How many times have you witnessed an athlete’s temporary change in behaviour? Only to come back next week and feel like they have forgotten everything?”

I received a few blank looks but after a warm smile, I knew we all have experienced this. It was a question asked in the book. This uncovers a disparity between Motor performance and motor learning.

Sometimes we pride ourselves on acute changes of behaviour (Behaviour in a skill acquisition sense). However, this is not always indicative of genuine motor learning. This is significant because a regression in motor performance is a sign that the athlete is either dependent on our coaching tactics or isn’t adapting to the learning environment that we have created. So then begs the question, how do we know that learning is taking place? Well, one of the methods is “Silent Sets.” Put simply a coach may employ silence in the athlete’s sets and gauge whether learning has taken place.

Coaching and attentional focus

“Attention is the currency of learning where mental investments determine motor returns”

When cueing athletes or explaining drills we aim to capture, keep and direct attention. The effectiveness of a cue is anchored to the accuracy and vividness of the imagery it provokes. Accuracy in this case requires the cue to capture the most relevant features of the movement an accurate representation of the desired outcome. I personally think of this as a difference between a Shotgun and a Sniper. Really good coaches seem to be snipers. This then moves on to where we direct our attention. If we notice a technical error, logic would tell us (coach and athlete) to zoom in on that problem. However, this creates a “Zoom fallacy”. Where the more our cues zoom into the technical error, the harder it is to change. “The closer you get to an elephant, the harder it is to know you are looking at an elephant”

Analogies

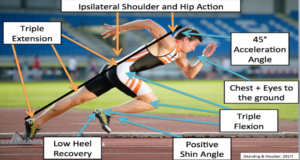

An analogy is a comparison between one thing and another, typically used for the purposes of explaining, it does have an interesting effect on the brain. Evidence suggests that language can literally put motion on the mind, providing support that analogies may help an athlete understand an unfamiliar pattern by learning it in terms of a familiar one. As you will see, an analogy is a sort of mental molecule that helps us make meaning. Analogies power our minds, allowing us to use association and comparison to expand and refine both our knowledge of the world and the way we move through it. Take these two for example, in relation to acceleration.

(Accelerate like a plane taking off)

Internal/External cueing

Now, we understand the power of analogies we can move nicely to internal and external cueing. Internally focused cues draw attention to muscles and body parts. For example, extending a knee, firing a quad or squeezing a glute. Externally focused cues, on the other hand, draw attention to the environment around the body. For example, pushing the ground away or driving the body off the line. Look below for some examples of internal and external cues.

| Internally focused cues |

| DB Bench press – “Extend your elbows faster” |

| Leg action acceleration- “punch your knees up & Forward” |

| Hip Hinge lowering phase- “Keep the bar close to your thighs” |

| Pull up “At the top of the pull, squeeze your shoulder blades down and back” |

| Externally focused cues |

| “Drive upward as if to shatter a pane of glass” |

| “Blast toward the finish” |

| “Hide your front pockets” |

| “At the top, bend the bar like an old school strong man” |

From this we can see a nice differentiation, with the same exercises. Nick is in favour of externally Focussed cues, he believes they are “Stickier” (Sticks in the athlete’s mind).

Constraints based cues

This wasn’t mentioned so much in the book, however, I found it had relevance. Constraints based cues. I was searching online to find a “Sniper” definition and here is what I found:

The CLA articulates that through the interaction of different constraints – task, environment, and performer – a learner will self-organise in attempts to generate effective movement solutions. (Renshaw, Ian, Keith Davids, Elissa Phillips, and Hugo Kerherve, 2011).

So by changing parameters such as the task or environment we can find effective movement solutions with minimal talking. A slight caveat to this (and some anecdotal experiences) is that the body will ALWAYS solve a movement issue however:

“The assumption that the body will figure out the best way to do something is a big jump to make.” – Chass pipit (Professional Baseball coach)

Often this is through compensatory mechanisms which are sometimes maladaptive. Just remember the good old strength and conditioning saying “Context is king.” However, it is safe to surmise that using a constraints led approach coupled with appropriately timed (and amount!) cueing could lead to optimal results.

Terminal vs Concurrent Feedback

Again, this did not have a major spotlight in the book but it has relevance. Terminal feedback refers to the feedback received after a movement is completed. Tasks which are acyclical in nature will lean towards terminal feedback. Concurrent feedback is experienced by the performer whilst completing the action, anyone wanting to know more on this should watch the video below.

This blog is in no way meant to replicate any parts of the book, for that matter is doesn’t even do it justice, full credit goes to Nick Winkleman for a stunning read. I wanted to conclude this blog by relaying the questions I ask myself when coaching athletes or anyone for that matter.

Could I of said it differently?

How can I have a leaner approach to cueing?

How do I assess genuine motor learning has taken place, in this instance?

Thanks for reading guys,

Konrad McKenzie

Strength and Conditioning coach.

Liked This Blog?

You might like other blogs on this topic from APA:

APA review of the Middlesex Students S&C conference 2014

The Dubious Rise of the Corrective Exercise ”Pseudo-Physio” Posing as a Trainer- My thoughts

as well as two recommended articles:

This article on weak Glutes during Squatting

And this one on Exercise Modifications

Do you feel that this would be a perfect time to work on the weak links that you have been avoiding? The things that you know you should be doing that you keep putting off? Would you like us to help you with movement screening and an injury prevention program? Then click on the link below and let us help you!

? TRAIN WITH APA ?

Aspiring Pro Training Support Packages

Follow me on instagram @konrad_mcken

Follow Daz on instagram @apacoachdaz

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM