Pacey Performance Podcast REVIEW- Episode 204 James Wild

This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 204 – James Wild

James Wild

Background:

James is the Technical Lead for Performance at Surrey Sports Park. He is also contracted to work with Harlequins to run their speed and agility programme for their first team squad. He teaches at the University of Surrey, heads up the athletic development for England Women’s Lacrosse and is also completing a PhD in Biomechanics and motor control of accelerative sprint running.

Discussion topics:

James on his approach to training in terms of speed for sprinters versus team sports.

”Ultimately sprint performance is determined by optimising our ground reaction forces. Ground reaction force production during stances is pretty complex and it’s influenced by multiple physical qualities and coordination.

There might be a little bit more of an individualised approach that can be taken to impact team athlete’s sprint performance. This is especially true as the positive effects of a more general strength programme diminishes as the athlete grows in terms of their training age and level of expertise and their strength levels. I think there’s more scope within a team sport setting to impact on an athlete’s speed compared to a sprinter who that’s all they’re training for. I think it’s a little bit more untapped.”

James on the four main areas he is most concerned with to help him build up a profile of the athlete and their sprint performance

- Current sprint strategy

- Injury history

- Strength related qualities

- Actual sprint performance- split times

”In terms of the sprint strategy this concerns some of the key technical markers and higher order kinematic variables such as step velocity, step length, step rate, contact time and flight time and how these variables change across the acceleration phase.

You can have different ways of being fast over the first 10 metres. It will probably be achieved in about seven steps, and you would expect to see that contact times will reduce with each step and the flight times will increase with each step. In the initial steps the contact times will remain longer than the flight times. This makes sense because we know that we need to generate large amounts of horizontal ground reactions forces to produce the horizontal impulse necessary to accelerate in those initial steps, and we can’t produce that force whilst in the air. Because of its importance it is possible that someone with shorter contact times (which could increase the number of steps) and someone with longer push-offs could achieve the same overall net horizontal impulse and therefore both be equally effective strategies.

It becomes a problem when it is too extreme, so if someone is really chopping their stride and producing really short contacts at the start, and they’re not going to be spending enough time generating that horizontal impulse on the ground.

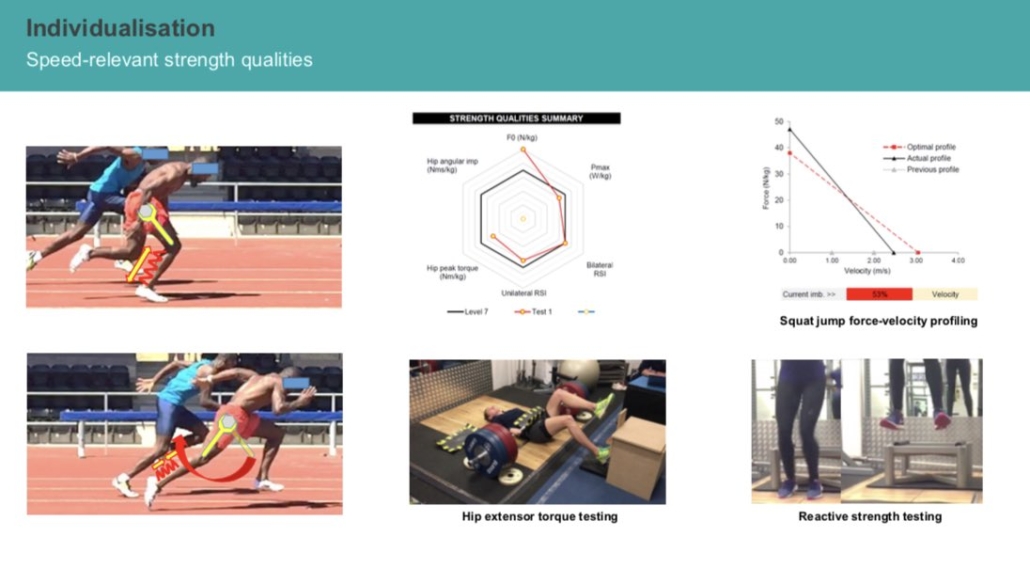

In terms of strength related qualities there are three main assessments I use:

- Hip extensor torque assessment

- Squat jump Force-Velocity profile

- Repeated jump assessment

The hip extensor contribution to the horizontal ground reaction force production is pretty well recognised now largely thanks to the work of J.B.Morin. It plays quite a key role in accelerating the centre of mass forward during the first stance phase. I look at peak torque and also the rate of that production. It helps me to identify whether we might need to slant the training more towards max force type work or more rate force type work with regards to the hip extensors.

I’ll also look at two angles around the hip; a more extended hip position for the more later stages of acceleration and top end speed, and then I’ll have a much more flexed hip where less emphasis is hamstring driven, it’s more towards the glutes related to the earlier stages of acceleration.

The squat jump force-velocity profile follows the methods of Samozino and his crew. We can work out peak power of the leg extensors, and it’s a bit more biased towards the knee extensors. We can look at the optimal levels of force and velocity that might be required at a given peak power to maximise that push-off performance that might be related to those initial steps.

This allows us to then tailor our squat-based pattern work to be more max force orientated, more force at higher velocity or concurrent development of both.

The third strength quality assessment I use is like a repeated in-place jump test for RSI. This allows us to get an idea of how they’re able to limit the amount of leg definition, so stiffness but also looking at how they’re able to store and release the elastic energy effectively. Once they’ve reached a certain strength level I feel like it’s quite important to become a little bit more specific with the approach taken.”

James on how he designs a training session using the profile information

I divide my speed sessions into five different sections

Drills:

- Low intensity activities

- Cyclic in nature

- Aimed at reinforcing favourable body position, rhythm and timing

Drills for me can be a really useful coaching tool, in my opinion, because they allow you to almost over-emphasis an aspect or body or limb position you’re hoping the athlete will find when they sprint. And the athlete can then ”hold onto” what that over-emphasis feels like.

Jumps:

- Selection decided based on theme

- Usually more horizontally dominant for acceleration

- More vertically dominant for max velocity

- Continuum for regression/progression

Priming activities:

- Pretty much sprinting

- Resistance sprint work (acceleration focused)

- Running over small hurdles (max velocity focused)

Free Sprinting or change of direction:

- Close to maximum capabilities

- Gradual increase to the distances covered and speed reached over time

- Athlete ideally needs to be fresh

Sport specific speed:

- Match conditions with constraints

- Gradual increase to the distances covered and speed reached over time

”The stage of the season or the logistics of that week, and individual needs of the players, will determine how many of those five components will be in an individual training session. In a typical 45-minute session I’ll usually cover four to five of those components. Whereas if less time is afforded such as towards the season, we might need to pick and choose from those five components which we feel are the most important at that time.”

James on protecting hamstrings

”I think one of the things to consider is that sometimes a hamstring injury just happens! And we can over analyse it and pull things apart programme wise. I think gradual exposure and progressive exposure to sprinting distances and speeds is important. Tied in with that is the technical focus of how they sprint. Then I think inevitably there needs to be some strength-based work for the hamstrings, eccentric and isometric and I have no problem whatsoever with nordics.

I think it’s really quite important to consider the strength qualities around the ankle. Do they have the reactive strength type qualities, the stiffness with the right level of compliance at the ankle joint? Because, if they don’t, then they most certainly are going to over stride when they sprint, and over utilise the hamstrings. Their strategy to run fast is going to be to over utilise the hip extensors to pull them through the start phase, rather than striking closer to their centre of mass and being able to spring off quicker as a result of a stiffer and tight ankle.

Also what’s their lumbar and pelvic control like? Are they weak through certain areas? Are they just lacking coordination? Can they not stabilise their pelvis because of, it might be simple things like the hip flexors want to take over everything, are they not able to counter that through their abdominals?”

James on coaching cues for improving sprinting performance

”Often for each individual they might need a combination of different cues that work for them. A lot of S&C coaches fall into the trap of seeing that their sprint technique has ”improved” and automatically think that they’re running faster. I can tell you that 99 out of 100 times, in that acute setting , if you cue someone and they change their technique from how they normally sprint, they will be running slower.

Now that’s absolutely fine if that’s part of a longer term strategy to try and shift them towards a certain technique. But I think we just need to be a little bit cautious in that they will be running slower in that acure situation. I think that sometimes it’s necessary to explain to the athlete that during a match or during testing or whatever, at a key time where they have to run as fast as possible, don’t think necessarily about changing your technique.

Now there might be a flipside to that, that if someone’s a real injury risk waiting to happen, then obviously you might want to adapt it.”

James on why S&C coaches are not as comfortable coaching speed as they are strength

”It completely makes sense, because if you think all those individuals, the amount of time they’ve spent training would have been more in the gym than it would have been out doing speed-related stuff. Then you consider that not all but a lot of educational programmes, degrees, courses out there, there’s probably a lot more emphasis on strength training as there is to speed.”

Author opinion:

Assess don’t guess!

It is clear that James has developed a very comprehensive assessment battery and has a very high knowledge of the sprinting technical model and the various components of an optimal sprint strategy. What was most interesting to me was the idea that in some cases it might be more optimal for an athlete to take more steps than the typically reported seven steps over 10 metres -provided an athlete can achieve the overall net horizontal impulse required.

Clearly in order to know this for sure James is able to measure specific variables such as step velocity, step length, step rate, contact time and flight time and build up a profile that isn’t just based on outcome measures of split times. He also uses a comprehensive strength assessment of not just leg extensor strength but hip extensor and ankle stiffness.

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Individualisation– the higher the level of the athlete the more important it becomes to have an individualised approach to improving sprint performance

- Build a profile of the athlete– don’t just look at split times, look at how they sprint!

- Little by little– gradual increase to the distances covered and speed reached over tim

- Technique timing– if you cue someone and they change their technique from how they normally sprint, they will be running slower

- Understand Key Technical aspects of Sprinting– in order to get more comfortable coaching speed then get out on the field more and actually coach it, train it yourself and understand the technical model.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

Email: j.wild@surrey.ac.uk

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM