Pacey Performance Podcast REVIEW- Episode 272 Hakan Andersson

This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 272 – Hakan Andersson

Hakan Andersson

Background:

Hakan Andersson– Sprint coach Sports Performance Consultant and Educator based at Sports Performance Center, Vaxjo, Sweden. 61 years old and 35 years coaching, with keen interest in Athletics and sprinting in particular. Retired in 2018 after 36 years in Fire Brigade.

Discussion topics:

Where would you actually start jump training and plyometrics with young sprinters?

”A local doctor really opened my eyes to sport science and he really introduced me to some great scientists. The first scientist I met in the flesh was Carmelo Bosco, and everyone had heard about counter movement jumps, rebound jumps and squat jumps. He was the Father of that and was doing a lot of pioneering work on the stretch shortening cycle in the mid 80s.

Sprinters have been doing jump training for hundreds of years but it was the Russians and Fins who took it to another level with more science and planning in an organised level.

When we talk about plyometrics what we probably mean is jumping (although there will be throwers that will object to that) so it’s some kind of ballistic movement and a wide spectrum of movement. Jumping is great for developing general and specific coordination, so it has definite room in the programme for everyone and the earlier you start the better. Everything you have to learn with coordination is easier if you start at an earlier age. Plyometric ability jumping seems to be like a natural thing to do growing up.

In a more structured training environment with young sprinters you have to start with building resilience, you can’t start with intensive jump training when you weigh 90 kg and you’re 30 years old. Before puberty you can start with rope skipping and hopscotch coordination. Jump training can be very intense, and neuromuscular tension and forces can be very high so you have to be careful and it can easily be overdone. It has to be individually monitored and progressed.”

Training load for plyometrics. How is that something that you moderate for your athletes? Ground contacts?

Ground contacts only say so much. It is also the height you are jumping from and how much you attack the ground. It is very easy to produce high ground reaction forces if you attack the ground or you are landing from high, so you can’t start in that way.”

Is there a way that you quantify how much plyometric training your individuals are doing?

”You can’t only talk about numbers and intensity. There is no perfect scheme, you also have to use your gut and see how people are responding to the training. You can’t say how many contacts you should be doing in a session, in a week in a month. It only says so much about the load.”

What other considerations are there for coaches using plyometrics with team sport athletes?

”Henk Kraaijenhof says Plyometrics is for cats not cows! It all depends what athletes you have. If you take sprinters you see a wide range of different body types. You have the greyhound, very light frame elastic type who often respond well to jump training and often respond negatively to heavier resistance training. Then you have the more muscular types that are usually more stiff, less elastic and usually respond better to heavier resistance. So it’s the same in the team setting; you have different kinds of players, and you have to treat them as individuals.

It can be very easy to overdo it and lead to injuries because of the intensity that can occur in some of the exercises. But I think that everyone can benefit from some type of plyometrics. You also have to take into consideration that it has a diminishing returns. If you talk about weight training, people may respond to the heavier resistance training and it may transfer to sport fairly well but there is usually a diminishing return where that last 20-30% of strength doesn’t really transfer, and it’s the same with plyometrics. If jump training was the best solution then jumpers would be the best sprinters but they are not! So there is a diminishing return there too.

If you can jump 16m with standing five jumps and run 10.20 seconds for 100 m does it mean you will run 10.0 seconds because you jump 17m? Not necessarily, but I think that everyone will benefit from jumping to some extent.

Take for example an ice hockey player and their season is over end of May/beginning of June and you start training them and you start with hurdle jumps you are going to run into trouble in a couple of weeks. You have to be very careful. He can jump but he can’t land because his feet are fixed in skates for months of the year. So it will be such a stress on the system, especially if you are on the heavy side.”

How would you modify the training for the sort of person you mentioned that may not respond as well to plyometrics? And what would you put in the programme?

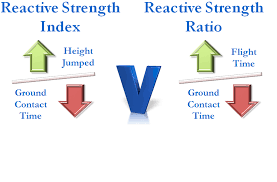

”First of all you have some kind of objective way of judging what kind of athlete you have. An experienced track coach can see who is elastic and who is not. You can also test people and use something like the reactive strength index, the relationship between jumping height or flight time and the ground contact.

People who display a high RSI usually are the elastic type, and most of the time you can expect them to respond well to jump training. If you use subjective means to determine someone’s type you need to have a lot of experience.

We used to test a lot. Nowadays we measure a lot in training to see how they respond, it doesn’t just have to be a testing session per se.

We used to use a counter movement jump and ask people to jump as high as possible but many times we saw no transfer to sprinting. When it comes to the RSI it’s a better test in my opinion, and if they score well in the RSI they are usually in good condition to run well. We have guys who score almost 4.0 with ground contact of 0.150 m/s. A good RSI is also related to power output, with high RSI you have a high power output and you see numbers exceeding 80 Watts/kg.”

How do you incorporate horizontal and vertical emphasis jumping into your training?

”Both horizontal and vertical places an important role in sprinting and I don’t really understand the debate between the vertical camp and the horizontal camp, they are so connected. Just like contact times versus contact length, people forget about contact length. We have to move the centre of gravity in stance phase in a certain time. Remember contact time is the outcome of running velocity. And the velocity at toe off is the result of the magnitude and direction of force, so they are connected. So if you try to mimic the ground contact of an elite sprinter at say 80-90 milliseconds then remember they have to move their centre of mass horizontally. If you try to mimic that by jumping vertically they are a totally different thing! So both forces play a big role.

In initial acceleration of course you can produce a lot of horizontal force and you can use the knee extensors more, and in top speed of course the vertical force is more significant but if we want to keep accelerating we need to make sure the propulsive forces are exceeding the braking forces.

Unilaterally bounding is more tricky and the forces are high because of the speed so it’s important to do this beyond just vertical jumping which may be good for training stiffness. The bounding is better for training hip extension.

In team sports I would probably do more horizontal jumping but it all depends on their experience. You have to respect the landing and the impact forces especially if you are a little heavier or jumping on a hard surface. You might start on grass or jumping up stairs, and the jumping height.

I would start with a skipping rope and see how they respond and progress it slowly. If they are coordinated and can learn it they can benefit from it.”

In terms of resisted sprints where would you start someone?

”Resisted sprints are an excellent idea for developing horizontal force capability in a safe way. We have being doing some form of resisted sprints for a long time such as hill sprints. In the last couple of years there has been some interesting technology come to the market. We use the Dynaspeed in Sweden and there is the 1080 motion, and there are lot of resistances that you can programme in and do it a lot more accurately.

Sprinting is all about producing rate of force in a short time in the right direction but it is also about rhythm, and coordination and relaxation. I find sometimes, and sprinters say it too, that sleds can be very disturbing because you are working with friction and the resisted force oscillate a lot when you are working with sleds.

The new technique using constant pulling force (dynaspeed) can be programmed so you can work in all the different acceleration phases, different loads and so we use it a lot and I think this will be a big part of the future in sprinting when it comes to being more precise and working more specifically, and more important than plyometrics actually.

You want more information than speed, I think. You want to see what happens to stride length and frequency when you load them with resisted sprints. Especially with assisted sprinting it is crucial to know, as it is very easy to pull people too hard, and you damage their mechanics.

The way I see it, if we use pretty heavy resistance and I programme the system to use say 30% of body weight equivalent or 60% body weight with a sled, friction dependent, the maximum velocity that you will achieve with a sprinter is roughly around 4-5 m/s which is equivalent to his first or second stride. So with a heavy sled it is like training their first few strides but for an extended period of time.

If you do lighter resistances you can work on different phases of the acceleration curve, so it’s a very good tool and you can work your way through the whole acceleration period starting your session. You start with a heavy resistance and the initial acceleration and you end up with the training programme developing the later part of the acceleration.

We usually use assisted sprints in the later part of a preparation period.”

When you say heavy resistance sprints what kind of load are we talking about?

”If you refer to the literature they are always referring to sleds. If you talk about motor resisted sprints like muscle lab or 1080 it’s usually about half the resistance. So the heaviest resistance we go to is about 30% of body mass, and that slows them down extensively to the speed of the first step. (which is equivalent to 60% on a sled).

We start with heavy sprints for a couple of weeks and then we reduce the load through the training period, and usually mix it too with super heavy, medium heavy and light weight but we emphasis one side of it and always with a combination of unloaded.

Resisted sprinting alters mechanics at the heavy end if you try to run with an erect position! If you stay in the same position as you would in the first couple of strides of acceleration then it obviously doesn’t alter mechanics but if you try to run in an upright position with 30% of your body weight then it would. ”

How would that work when you are working with team sports?

”The heavy resisted sprinting would be more considered strength work. In football, sprinters never start their sprints from the true low acceleration position, they start from a more upright position so they have to accelerate a lot more with hip extension than knee extension, like a sprinter would.

In a game scenario a footballer starts a sprint from a more upright position, or from a moving position, and never from a low stance.

So the heavy resisted work in a low position is beneficial if it is seen as strength training for them. For people who can’t do a lot of jumping it is a safe way of working even if the resistance is high and the speed is low, it is still much faster than anything you can do in the gym.”

What are some of the testing options have we got to help coaches decide where to spend their time?

”I think timing sprints is important to ensure the intensity is where you want it to be. Hand timing is fine but electronic timing can help further. It is much easier to monitor. Electronic timing is a good investment.

We are now using IMUs with Musclelab that can detect ground contacts at touch down and toe off so we can calculate stride frequency, contact time and flight time. If you can measure speed every time we also have the contact and stride length. So we can follow the stride kinematics and kinetics as the athlte

We use Ergotest company based in Norway. Musclelab is the brand and we use 16G IMU can sample up to 1000Hz, wireless and put it on the laces of the shoe.

Force platforms are great for seeing how they produce force eccentrically and concentrically, as jump height is not enough so that is another useful metric to see how athletes produce force. I’ll use the force plates when doing drop jumps and counter movements I have replaced the contact mats with force plates as I feel I get more information from that.”

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Start early- everything you have to learn with coordination is easier if you start at an earlier age. Plyometric ability jumping seems to be like a natural thing to do growing up.

- Progress slowly- build resilience and it has to be individually monitored and progressed.

- Monitoring jump load- it has to be about more than just ground contacts. How much you attack the ground and how high you jump must also be taken into account.

- Transfer to sprinting- If jump training was the best solution then jumpers would be the best sprinters but they are not! So there is a diminishing return there too.

- Direction of force- Both horizontal and vertical places an important role in sprinting

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

Twitter:

@sprintcoachSWE

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM