Pacey Performance Podcast REVIEW- Episode 292 Loren Landow

This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 292 – Loren Landow

Loren Landow

Background:

Loren Landow

As of March 12th,2018 Coach Landow is now the full-time head Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Denver Broncos Football Organization. He maintains his ownership/founder of Landow Performance in Centennial, Colorado.

Discussion topics:

Tell us a little bit more about your background and education

”When I came out of school (did a degree in Kinesiology with a minor in Nutrition) I got involved with my first mentor Greg Roskopf who was the developer of the Muscle Activation Techniques. I took a year long course which was pretty intensive and extensive, and during that time I was still working with and training athletes and used my Middle school athletes as my guinea pigs in 1997-98, and trying to figure this thing out that we call performance training.

I got involved with Velocity Sports Performance through Lorence Seagrave, and around that time I got to know Dan Pfaff, which was followed by the start of Landow Performance, and the vision I had. This vision involved needing a lot of space to train athletes in, and I wanted to pay people really well, who could make a living in this field and not having to worry about holding down two or three different jobs to pay their bills. At the time of writing I have 30 staff and around 12 what I would call full-time staff.”

In your UKSCA presentation why did you put so much emphasis on the importance of frontal and tranverse plane drills?

”Steven Plisk, who is another mentor of mine, always said that in periodisation and programming:

to be a better specialist you need to be a better generalist

To be a sniper in our field you need to understand your biomechanics, anatomy, biochemistry, programming and all the different subject matters which make up what we do; you have to be really good at those general subjects to really dive in to be able to give somebody something pretty specific and pretty individual. When we look at movement, there are infinite movements we can do, but when you really break it down to fundamental quadrants and cardinal directions, what can you really do in those planes?

So I started breaking it down, not reductionist, but a generalist mindset, and say ok, if I can be really good in moving in the sagittal, frontal and transverse plane those are really the crux of how you build change of direction. At the end of the day I’m going to use a transverse or frontal plane type of movement to bridge two gaps of acceleration.

People talk about reacting to the environment, and the environmental constraints…well we have constraints within our body, and if we are not a good locomotive athlete, not a good mover, we don’t understand fluidity and coordination, you can make the environment as dynamic as you want, I don’t think I am going to be as efficient as I could be, as if I spent a decent chunk of time mastering myself and how I move in space.

When it comes to structure and function you can really narrow all common movements down into four common forces:

- Shear

- Distraction

- Torque

- Compression

So if I can build closed models where I work on the robustness of the athlete, and marinate in those movements to make you more resistant to the torque and shear forces that take place at the knee joint, I do believe we can teach the body and the neuro-muscular system to be more robust against those types of forces, when we are exposed to them on the field.”

What teaching progressions do you use when you are teaching an athlete from scratch through deceleration?

”I’ll teach them good squat and lunge patterns in the isometric fashion and being able to get into those bent knee positions that ultimately look like deceleration, and I’ll do that even with my elites as they don’t bend and move as well as you would think. Maybe it’s because of their training age saturation, and maybe they just didn’t seem to care when they were going through these rudimentary stages of learning. For me, it’s not that I want to make everything closed, because I’m very big into open movement. But I think early on you have to teach some closed patterns.

I’ll start with different skipping patterns then they’ll have to absorb into a BILATERAL deceleration, they might start with jogging and sitting down into the squat position. But once they start having better control with that, I’ll take it into a light acceleration and then we are going to decelerate into a split stance. So those of the kind of things I may pay attention to early. The thing I love to do, say I’m doing a linear acceleration, is put on the brakes into a good deceleration, then I’ll take them into a back pedal action and have them put on the brakes. Now I’m getting that good deceleration, eccentric loading in those reverse mechanics and I get great deceleration on the achilles. Over time there are some good things happening in terms of tissue tolerance and I do these things at low intensity. Things are progressed over time and that ultimately becomes, okay, you’re going to accelerate for 15 yards and put on the brakes at 7 yards; now you’re going to put on the brakes at 5 yards, now at 3 yards, now you’re going to put the brakes on when I clap. So there are different ways to make these drills go from closed to open.’

[Daz comment: check out this article ”Taking a step back to reconsider change of direction and its application following ACL Injury] There was a very interesting reference to research looking at what percentage of maximum speed could be attained prior to changing direction- in this case back pedal].

Eccentric control of pronation/supination

Principles change based on foot position. When we are jogging, running and sprinting, there are different elements of stride pattern and positioning. When I’m in a frontal plane it’s on the edges, I start to use the inversion/eversion qualities of the foot, still pronation/supination of the foot but it’s in a different plane so I’m stressing those structures of the foot differently up the chain. You don’t want too much of one , or two much of the other so how do I find the ability to manage and mitigate both supination and pronation? I love the side shuffle drill. Even though in sporting action it’s usually one step and go, I like to saturate the skill and put them under different forces and different loads so they absorb those forces.

In terms of ongoing assessments during training how are you identifying where people are potentially having energy leaks and where you potentially need to spend more time?

”I used to think that you take someone out of their shoes and you see them squat or lunge and you see this great contoured [high] arch, and you’re like, that’s a strong, stable foot, that’s great. And it might be, but in many cases we see people who get their dorsi flexion from their phalanges (toes), and what happens is that they actually keep the mid-foot plantar-flexed so the foot still looks like its got that contoured arch, and that’s not a good thing because the talus can’t move and glide.

What I look for now is you need to have stiffness in the foot, but you need to have compliance in the foot. You need the fore foot, mid foot and rear foot mold and adapt to that flooring, and so you do want that, it’s just a matter of degrees. So now, I actually look for someone who has a little bit more of a flatter foot, a foot that can actually splay (spread) to the ground, not arch up, because that’s when you get those intrinsic stabilising and eccentric control. When the foot is clawing that’s more of a concentric action, and I want more splay that creates more eccentric control that allows me to have cleaner motion from the rear-foot, mid-foot and fore-foot, not to mention the ability of the talus to glide and the tibia to move forward and back really well.

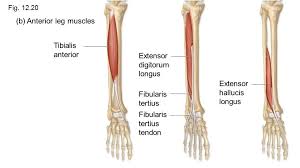

[Daz comment: the muscles in the anterior (aka extensor) compartment are responsible for dorsiflexing or extending the foot. Extensor digitorum longus extends or lifts the second to fifth toes. Extensor hallucis longus extends the big toe, aka halux]

So now I ask an athlete to dorsi flex and if they are pulling up more from their extensor digitorum (longus) and extensor hallucis (longus), more than their anterior tibialis, you’ve got to pay attention to that. Because if you just look at dorsi flexion with shoes on you are going to be biased to what you are seeing.

The problem when people start doing ‘barefoot’ work is that they go for the gusto! It’s not about sprinting in barefoot, it’s about doing these intrinsic movements (such as standing on two feet or one foot and rotating around your feet to feel the eversion/inversion etc) to get you a better foundational stability. I may squat them and do lunges but I think people are getting a little too carried away doing all their locomotive drills barefoot. Is the juice worth the squeeze for the risks/benefit?

The knee is the servant of the foot and the hip, emphasizing the importance of what is going on above and below. The foot has more than three degrees of freedom, so there is a high availability of movement and therefore instability and the hip is the same thing. The knee doesn’t have that, it is mainly sagittal, it has a little bit of rotation but not much so at the end of the day, if you are unstable through the hip and/or foot that knee becomes the torque converter through what those two joints maybe can’t decelerate, so to me it is really important that you have a programme that looks at the eccentric control of these joints. People get hyper focused on the knee, especially during injury, and they’re not spending enough time working on the foot and the hip, and the trunk!

If I’m constantly giving you a cue or something to change, you’re never getting a chance to feel something on your own.

- Posture

- Patterning– rhythm

- Positioning– limb positioning

- Placement– foot strike (what part and where is it hitting the ground)

The first two are the most important to me, and then what I do is I think what are the three drills I can use that can influence all of those factors. Going back to that generalist specialist idea, if I take care of those four P’s a lot of the rest of it takes care of itself. I find drills that are marching, skipping and running in nature and will allow me to replicate that. And then, when they get on the field, they will self organise, do what you do when you play your position.

Tissue tolerance vs Motor Skill

People might get the wrong impression that all I do is closed drills, and that couldn’t be further from the truth! One final thing I want to stress about my philosophy is that it is a periodised view of movement. Yes early in my off-season we will do more closed drills, more rhythm based, such as shuffles and cross-overs. Then I get into closed drills that have a deceleration emphasis, then I get into open drills, where you don’t know when you’re stopping.

People always talk about motor learning and you should never do the same drill twice. Well, yeah, that’s great but how do I get stronger on a bench press? Do I get stronger by doing one rep on a bench press, then go do a rep on a single arm DB press, then do a rep on an incline? No, you have to SATURATE!! If we talk about the Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands (SAID principle) I have to impose enough of a response to adapt to.

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Be a Generalist- to be a better specialist you need to be a better generalist

- Common forces- you can narrow all common movements down into four common forces: (shear, distraction, torque, compression).

- Eccentric control of foot- appropriate dose of barefoot work to strengthen the intrinsic muscles of the feet

- Four Ps of Coaching observation- look at posture, patterning, positioning and placement.

- Tissue tolerance vs. Motor Learning- you have to ‘saturate’ a drill to impose enough of a demand on the structure to adapt.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

Twitter:

@LorenLandow

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM