Pacey Performance Podcast REVIEW- Episode 373 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar-Newman

This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 373 – Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar-Newman

Jeremy Sheppard

Jeremy is a strength conditioning coach with Canada Snowboard, previously having also worked with the Canadian Sport Institute.

Dana Agar-Newman

Dana is a senior practitioner at the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific, and a head strength conditioning coordinator at the University of Victoria. He has also worked in rowing and rugby, including with the Canadian women’s rugby sevens team at Rio 2016.

The duo have recently written the jumping and landing training chapter in High Performance Training for Sports (second edition).

? Listen to the full episode with Jeremy & Dana here

Discussion topics:

When it comes to jumping testing and analysis what options have we got?

”Thinking about how we’re testing jumping is more important now than ever as technology is expanding rapidly. There are a number of tools out there that can give you a number for jump height but it may not actually be how high that athlete has truly jumped- their centre of mass, it may not even be a valid number. So it’s really important to know how jump height is being calculated with the tool that we choose.

Even if we are using something like a force plate our choice of software can also impact whether we go with one company or another.

Flight time Method

- My Jump – iPhone App – through frame rate of your camera

- Opto jump

- Jump matt

Another tool is something like a Vertec, and now a lot of us are using force plates using single or multiple force plates so you measure asymmetries and that uses the impulse-momentum method. That;s important to know because all those tools give us a slightly different measure, so you’ll jump higher using the flight time method often than you will using the impulse-momentum method using the force plates. The reason why is because the flight time method assumes you take off and land in the exact same position when in actual fact most athletes are going to land with a slight flexion of the hips and knees, and slight dorsi flexion in the ankle so it will inflate the jump heights slightly.

Each tool has advantages and also cons.”

Measure What Matters

When it comes to identifying the metrics we want to analyse how does that conversation differ between sports?

@Dana: ”You should always take your testing and try and compare it to the KPIs or your sport because there are so many metrics that come out of a force plate; I think in our script right now there are 90 metrics maybe even more, but you should really be trying to narrow those down because a lot of those metrics may be telling you the same story and a lot of them may not actually be that reliable.

So start with that, and then with the metrics that are reliable then you want to be comparing them to the key actions and KPIs within the game, so when this metric moves, that metric moves in the game as well.

You can look at different levels of athlete, that would be your basic level of analysis, so are these metrics different in lower level athletes compared to say higher level athletes. Then you could look at a regression approach where you are predicting performance on the y axis and the force plate metric on the x axis; if the force place metric moves I know that I can expect to see a certain movement in this performance metric. And probably a more advanced way of doing it is to look at the individual level so you’re saying with this individual athlete, when this metric moves I expect to see this metric to move over here in this KPI.”

@Jeremy: ”Take volleyball for example, there are some sports where the KPI is the outcome of the jump, and the outcome of the jump is how high you jump. That’s really important not to forget, and the variables we look at can help us to differentiate individualised training but there may be variables within a jump or even a something like a style of jump or a context that never or rarely occurs in the sport but it has a relationship to a component, and that component relates to the KPI skill.

So if I think of the spike jump in volleyball, where you have an approach, well you might say there is no depth jump involved. But what we found, and what we have repeatedly found over and over again, is that depth jump performance is related to your ability to attenuate those forces in your approach and convert from horizontal to vertical.

If you’re looking at measuring the spike jump performance in context there is so much noise, but if you take a depth jump that’s very repeatable, and that depth jump relates to that transition ability of horizontal to vertical. So the influence of the depth jump and its unique way of developing or in this case testing the stretch shortening cycle relates to your ability to take those steps and then transition in the penultimate step to convert into a vertical displacement. It’s not cause and effect but it has a high influence on that. So then you connect those dots to the actual performance.”

@Dana: ”there is a big push to make testing super super sport specific, but we already have a sport specific test and that’s watching the game! The question really comes well why is this athlete not able to jump as high as possible above the blocker (to use Jeremy volleyball example). You need to take the test and make it more general. Another example would be a lot of these aerobic tests that have become super sport specific. Well if the athlete tests poorly on it, well was it because they had a poor vVO2, poor change of direction ability, their anaerobic speed reserve wasn’t that big? You’ll still left with the question, what was the limiting factor with this athlete, and there is a place for making the test more general.”

Are there any considerations for individualising training for youths versus seniors or males versus females etc?

Youth vs Adults

@Jeremy: ”You need to learn your context, which is not a quick fix if you are new to the sport. You might do your neuromuscular profiling but with children you might identify some really great things to do but I’m still not going to do them because of a myriad of other reasons, because of their biological ability to tolerate that load, because they might be growing fast, and because we want to be here for a good time and a long time, so you might subordinate the ”correct thing” muscularly in the hierarchy of training needs because they have so much gain to make elsewhere.

The analogy I make with this, is similar to nutritional supplementation – I do not like to buy nutritional supplements for athletes who cannot drive past a McDonalds because what’s the point? You have to earn the right to be in the penthouse suite and you have to have a foundation. So that 15 year old might need a lot of other things first, and it’s not that the cool neuromuscular stuff is not important, but they are getting a lot of jump volume from playing the sport, and maybe I don’t want to add to it until their movement is better, their knowledge of recovery and regeneration is better. If I keep adding highly individualised neuromuscular training just because I can, and my ego says that that makes me feel better at the end of the day, I may be creating a false economy and a false message. So what me measure matters as it communicates to our athletes what we think is important.

You train a dog, you coach people. So it’s about the bigger picture of education.

Men and Women

One of the challenges is if you have a sport where they depth and participation is really low it can actually be difficult to make well intended differentiation between men and women. Whereas a sport like volleyball is wonderful because the participation is high and the depth is tremendous. And so I find myself looking at trends in stature and strength levels and looking at ”people who present this way, rather than men who and women who,” as the top level of men and women because the participation in both sexes is really high.

@Dana: ”As athletes move up in sport, the top level can be quite homogenous, so a variable that could separate high and low level performers may no longer separate elite performers and the metric you look at maybe slightly different depending on your population.

The analogy I like to give is that if you’re going to a dance to find your life partner, the metric you need that $15 to get your ticket to the dance. But once you get into that dance, your dancing skill begin to matter. Can you dance? So money matters initially, but later on it’s something else, can you dance? It’s the same thing with testing athletes. Certain things may be important when testing low level athletes, and may no longer separate the population with higher level athletes.”

I’d love to get some insights and your process you go through when choosing exercises for jump training?

@Dana: ”In diving the youngest divers I get in the weight room are 12/13 years old and the oldest diver at the Toyko Olympic games is 27 years old. So a very different thought Initially it is all about teaching them a wide variety of movements in the gym, teaching them to land properly and teaching those skills and maximising training days. With the higher level athlete it comes down to the assessment driving the exercise selection.

- Loaded Jump profile – squat jump

- Isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP)

- Counter movement jump (CMJ)

- Depth jump profile

From those tests there I’ll choose my variety of exercises along with a conversation with the coach to see what they are seeing technically. So there are some things that are really hard to measure if you get stuck using that single tool. It gives you nice easy numbers to interpret but I think its really important to go back and observe that athlete qualitatively [performing their skill].

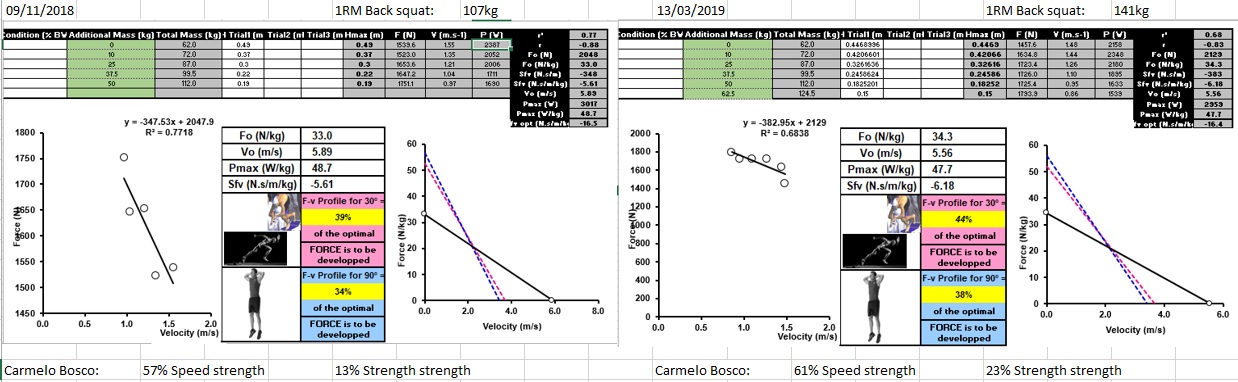

Initially I was really big in doing the Force-Velocity (F-V) profile with my higher level athletes and training off the F-V profile. I was finding results exactly you find in the research, where everyone’s jump heights improved initially, but after a while, once they are optimal (and the divers got to optimal really quickly because they were doing a tonne of jumping every day and training consistent in the weight room). So what I ended up doing is biasing them to more Force dominant in the off-season and then I would try to shift them to optimal (doing more velocity work) and sharpen the knife leading into competition. What I found is that if I was trying to keep them at optimal I wasn’t moving the needle at all.

The Depth Jump Profile

If you find that you need to work on the more elasticity and stretch tolerance of the athlete something I would also recommend is to jump off a series of increasing heights and the key thing to note is that athletes should be experienced at depth jumps. If they are, what you will find is that athlete’s jump height will continue to increase as they drop from increasing height up until a certain point and then it will start decreasing again.

So the question myself and Jeremy discuss often is, should we train at the optimal height where they jump highest or are we better to train slightly at the deflection point where they are starting to come down again?

For me in the off-season I will train at the deflection point and then leading into season I’ll train at the optimal where they are jumping the highest. I don’t have any research to back that up but it seems to be working.

@Jeremy: ”I’ll do jumps above that deflection point and some times much higher but they just land- because landing is so critical to snowboarding. I’ll also do jumps below optimal but it’s a different style/skill, where I don’t instruct them to jump as high as possible. Having them do these lower heights where the point is not necessarily to optimise the impulse, it’s to basically get off the ground as quickly as possible, so it’s a different style and when I write that in the programme its a drop jump, not a depth jump.

Is programming for a sport that has one big jump different from a sport where you have to jump hundreds of times a game?

@Dana: ”I think that comes down to conditioning. You need to train what you do, so you need to increase your capacity of movements, as well as how high you can jump, and both of those things are important. In a sport like volleyball to build that repeatedly I probably wouldn’t be doing that much stuff at body weight, I’d probably doing a few things to stimulate qualities such as doing heavier and lighter than bodyweight as they are already doing so much jumping at bodyweight. I’d probably also be looking to implement a few worse case scenarios in training, and looking if they are already getting that in the training. If they are then I wouldn’t be doing that outside of the training session in the weight room. But if for certain athletes who aren’t getting enough game time to stimulate those physical qualities you may need to pull it out to a more general setting to stimulate certain qualities. So you have to look at what they are getting out of the sport and then fill in the pieces.

@Jeremy: ”What happens when you working in a sport like Volleyball where there is so much jumping you’re going to have the good fortune of meeting a freak, who has an extraordinary physical quality or skill and in volleyball that shows up often because you’re testing jumping all the time. Your outlier in the vertical jump can often be your least well rounded strength trained athlete. In the gym setting and any other strength assessments you do, they are not the impressive one and they are often one of the ones you are most concerned about and don’t test well.

Where that will manifest is that they will have the largest drop in their jump sustainability in say their 1st set to their 5th set, or over the course of a tournament. Now you could argue that that’s okay because even at the end of the match or the tournament they are still jumping better than other people, but it still leaves clues what you’re looking at.

Leave your ego at home thinking you’re going to part of a project to take a 100 cm vertical jumper and take his vertical jump and make it 105 cm because really the work that is punching you in the face, is if someone is dropping that much over the course or a match or tournament, that opens up a big window of probability of injury because they are playing until tremendous fatigue and literally speaking they cannot handle the rigours of the sport.

And if they are this alpha that is a major athletic quality on the team then the success of the team is related to their ability to stay in the match, and so the work might actually be the boring stuff, and the actual job to be done is movement quality and making them neuromuscularly stronger that’s going to make each landing less fatigue inducing. So you don’t change the game but the game is now relatively less fatiguing for the athlete. So what you have to put your ego around is the fact that you’re going to make your 5th set performance much better!

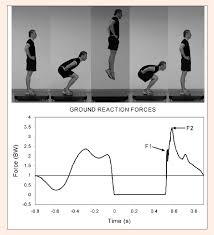

@Dana: ”In terms of landing during jump assessments, how the athlete lands can influence the metrics you are seeing. For example, if you absorb the force over a greater time you are going to find lower peak force and that comes down to impulse (which is Force x time) which is essentially your change in momentum. But absorbing force over greater time may not be applicable depending on the sport you may be working with, and so you may have to absorb that force quicker so there will be a higher peak force to get that same area under the curve. So the jump strategy should be sport dependent and the strategy will influence what metrics you are doing to look at.”

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Sport KPIs- You should always take your testing and try and compare it to the KPIs or your sport

- Indirect KPIs – something that rarely or never occurs in the sport but it has a relationship to a component, and that component relates to the KPI skill (e.g depth jump vs. approach spike jump in volleyball)

- Signal vs the Noise – there is a place for general tests to best identify limiting factors in athletes.

- Training at the optimal jump height – case for training at the deflection point and then leading into season I’ll train at the optimal where they are jumping the highest.

- Jump sustainability – athlete with largest drop in jump sustainability is often biggest injury risk.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM