Should Tennis Players Train Overhead?

Hi everyone! In today’s post I’m going to speak about a topic which has been really important for me to get my head around over the years as a coach working almost exclusively in Tennis – and that’s training overhead.

Shoulder related injuries account for a large percentage of repetitive injuries in Tennis along with lower back issues and ankle sprains. So given that the shoulder area already has to deal with a huge amount of stress just from playing the sport we do need to tread carefully with our programming, as it relates to training overhead.

In a recent discussion with one of my coaches I was pretty upfront in saying, ”I’m not a fan of programming Barbell overhead presses and Barbell bench presses.” His reaction was a lot like many I had seen before, bewilderment, because perhaps it was taken as if I was saying I’m against getting strong at pushing in the horizontal and vertical plane!

Quite the opposite – I think it’s really important to get stronger at pushing in the vertical and horizontal plane but I don’t think the bench press and overhead press are the best options for a tennis player, and certainly not a barbell version.

In this blog I’ll address why I think that way, and I’ll also pay respect to a couple of practitioners who have inspired a lot of my thinking in the past and continue to lead the way in strength & conditioning applied to baseball – Eric Cressey, of Cressey Performance and Ben Brewster, of Tread Athletics.

I did write an article Why Our Tennis Players Aren’t using Olympic Lifts – which is a topic for another day but it goes along the same lines – it’s about the cost-to-benefit ratio of these types of exercises in a special population of athletes.

One of my favourite comments from Eric Cressey goes like this ?

”Many of you are going to hate me for what I’m about to say. I don’t let my overhead throwing athletes overhead press or bench press with a straight bar.

There. I said it. Call me all the names you’d like but ask yourself this:

Am I cursing Eric’s name because I think that the cost-to-benefit ratio of overhead pressing and straight bar bench pressing justifies their use, or is it because I feel naked without these options? I have to bench press. I can’t start an upper body day with any other exercise.”

Early in my coaching career I literally read every article from Eric’s blog, I’ve also personally purchased most of his products and most of what I know about the shoulder I have Eric to thank for.

This post won’t go into the functional anatomy of the shoulder joint so if you want to do a deep dive on this I highly recommend you check out Sturdy Shoulders or Optimal Shoulder Performance. With that been said, let’s get into today’s topic and kick off with the Bench press!

Why I don’t like the Barbell Bench Press

Reason #1 – It doesn’t train scapular movement effectively

I read an article by Eric in 2010 – Should Pitchers Bench Press?

In it Eric says ”As it relates to pitching, the fundamental problem with the conventional barbell bench press (as performed correctly, which it normally isn’t) is that it doesn’t really train scapular movement effectively. When we do push-up variations, the scapulae are free to glide – just as they do when we pitch. When we bench, though, we cue athletes to lock the shoulder blades down and back to create a great foundation from which to press. It’s considerably different, as we essentially take away most (if not all) of scapular protraction.”

With dumbbell benching, we recognize that we get better range-of-motion, freer movement of the humerus (instead of being locked into internal rotation), and increased core activation – particularly if we’re doing alternating DB presses or 1-arm db presses. There is even a bit more scapular movement in these variations (even if we don’t actually coach it).

Reason #2 – It adds non functional mass and potentially reduces functional flexibility

The range of motion is a little bit less with a barbell version but athletes like it because that allows them to increase the load on the bar and potentially add on some muscle mass. The issue is that this muscle mass could lead to restrictions in shoulder and scapular movement – which won’t carry over to throwing the way the muscle mass in the lower half and upper back will.

This is probably why we don’t see an abundance of literature pointing to the correlation between bench pressing strength and pitching velocity (in the same way we might see between Rugby players with bench press strength and bench throw power output and playing level).

We want athletes with good range of motion in external rotation at the glenohumeral joint of the shoulder and horizontal abduction. This generally means exercises which promote length of the pec and lat muscles are favourable.

As Eric says, ‘‘what you do in the weight room has to be highly effective to justify its inclusion. I just struggle to consider bench pressing “highly effective” for pitchers.”

Eric Cressey has a free presentation – Individualizing the Management of Overhead Athletes – which I’ll briefly highlight some of the key take home points in another blog. But if you want to see the whole thing sign up to his newsletter on his home page.

Why I don’t like the Overhead Press

My thoughts on this are similar to the bench press argument. Despite my years in Tennis I have to be honest and say that more of my focus (at least in my blog) has been on lower body strength/power.

So if you want a good series to read check out on Eric’s blog check out:

The Issue with Most Powerlifting-Specific Programs

Should We Really Contradict All Overhead Lifting

How To Build Back to Overhead Pressing

The main summary is that overhead pressing using a barbell or dumbbells allow a lifter to take on the most load, and in the case of the barbell, they have the least freedom of movement (especially if we’re talking about a Smith machine press). Moreover, they generally lead to the most significant compensatory movement, particularly at the lower back. I don’t love these for tennis players.

Reason #1 – Throwing athletes are already predisposed to shoulder injuries

Overhead throwing athletes (and pitchers in particular) demonstrate significantly less scapular upward rotation at 60+ degrees of abduction.

Laudner KG, Stanek JM, Meister K. Differences in Scapular Upward Rotation Between Baseball Pitchers and Position Players. Am J Sports Med. 2007 Dec;35(12):2091-5.

From that study: “CLINICAL RELEVANCE: This decrease in scapular upward rotation may compromise the integrity of the glenohumeral joint and place pitchers at an increased risk of developing shoulder injuries compared with position players. As such, pitchers may benefit from periscapular stretching and strengthening exercises to assist with increasing scapular upward rotation.”

So if we know they are already at increased risk of developing shoulder injuries shouldn’t we be searching for the least stressful forms of overhead exercise? For the record, I don’t consider the overhead press to be one such exercise. I explain more below.

Reason #2 – Overhead pressing doesn’t train scapular movement effectively

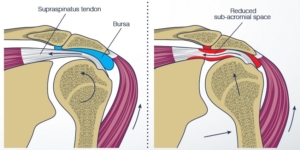

Impingement of the shoulder happens when we close down the space between the humerus and acromion. This usually happens when we get more rounded in our posture, causing our shoulders to internally rotate more. More external rotation = more sub-acromial space. How much internal or external rotation we get is going to be affected by the position of the bar (front vs. back vs. dumbbells) and the chosen grip (neutral corresponds to more external rotation- of humerus). Certain exercises will require more internal rotation and when used in excess – something like a barbell overhead press is typically going to make impingement worse, and a large percentage of the population really can’t do it safely.

Subacromial impingement syndrome refers to the inflammation and irritation of the shoulder tendons (rotator cuff tendons) as they pass through the subacromial space. This can result in pain, weakness, and reduced range of motion within the shoulder.

Reason #3 – We want more Traction and less Approximation

Additionally, comparing most overhead weight training movements (lower velocity, higher load) to throwing a baseball (or serving in Tennis) is like comparing apples and oranges. Throwing a baseball is a significant traction (humerus pulled away from the glenoid fossa), whereas overhead pressing is approximation (humerus pushed into the glenoid fossa). The former is markedly less stressful on the shoulder – and why chin-ups are easier on the joint than shoulder pressing.

Reason #4 – Overhead Pressing requires adequate shoulder flexion range

As a final plea, if you really are dead set on doing overhead pressing (with a barbell particularly) I’d just caution you to do some form of clearing test to check the athlete has adequate overhead range of motion.

The fist to fist test is just a start point to highlight that there may be a restriction – although it is supposed to encapsulate external shoulder range of motion, shoulder flexion and horizontal abduction (of top hand) and the opposite in the bottom hand- it’s not a complete picture. So in order to know exactly where the restriction is you would need to do a follow up assessment of things like T-spine (lumbar locked test or seated rotation), scapular (shoulder flexion and abduction) and humerus (total arc of motion in external and internal range combined).

As shoulder flexion is a pretty key driver of overhead movement it’s generally a good idea to assess that in isolation. There are many versions you can do – seated, standing and lying down. If the only way you can drive overhead motion is with compensatory lumbar extension then you know that there is no sense in doing loaded overhead pressing (especially with a barbell!)

So what are the Alternatives?

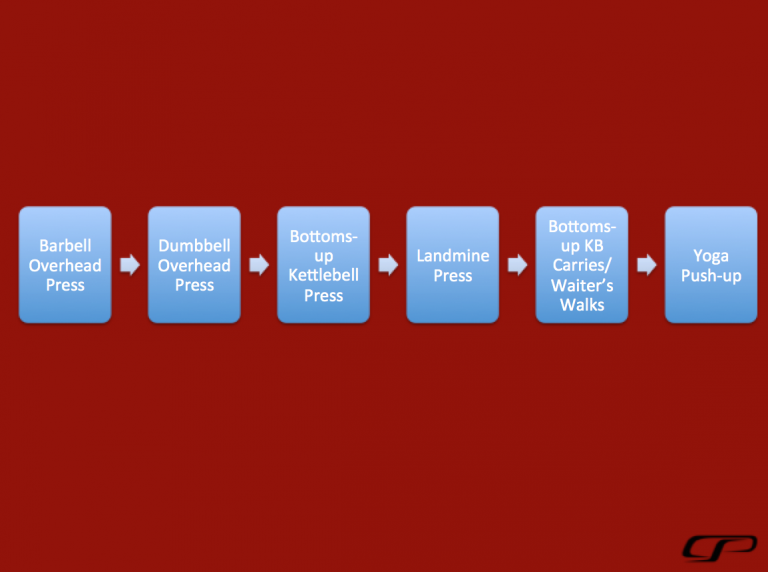

Below is a great visualisation of the spectrum of overhead exercises. At the most aggressive end of the spectrum, we have overhead pressing with a barbell or dumbbells. They allow a lifter to take on the most load, and in the case of the barbell, they have the least freedom of movement.

At the other end we have some options as more shoulder friendly exercises that can deliver a great training effect in more at-risk populations (i.e., tennis players). The bottoms-up kettlebell military press delivers a slightly different training effect more safely because more of the work is devoted to joint stability. And, the bottoms-up set-up helps the lifter to engage serratus anterior more to get the scapula “around” the rib cage

Also check out this brilliant video from Ben Brewster of Tread Athletics

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM