Are you a good Story Teller?

A few weeks back I received an email from a parent who felt the session her son was doing with one of my APA coaches was not individually tailored to her son’s needs. Individualisation is one of the key principles of training- as you can see in the graphic below it is also a key principle of customer service in business (in this case the customer is the parent and her child).

General Training is Specific to Untrained Athletes

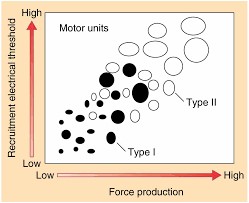

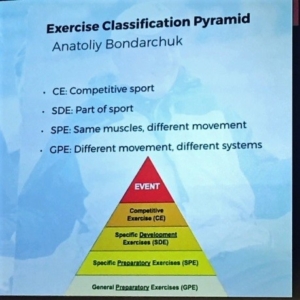

I’ve made my feelings clear on this topic several times before. Sometimes it gets interpreted that I don’t believe in sport specificity, or even individualisation. Technically speaking, that’s not accurate- however I will say that in athletes with low training age I do feel that EVERY athlete regardless of sport- needs to learn and train the fundamental movement skills in the gym associated with ‘resistance overcoming.’ By that I mean the fundamental patterns of squat, lunge, push, pull, rotate, brace.

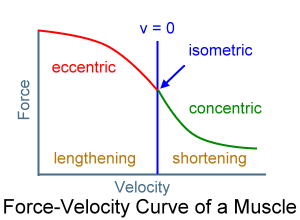

I also believe that if an athlete is weak then they need to learn to express force with the exercises which are best suited to doing that- exercises such as squats, before we start getting overly concerned with how closely the squat simulates the joint angles of the sport. I call this putting the ‘cart before the horse,’ and obsessing about KINEMATICS (Direction of Force-joint angles and contraction types) before getting the basics done with KINETICS (Magnitude of Force).

However, there is a big BUT…………..you must be a good storyteller and show the athlete how this exercise (which is perceived as not sport specific) IS ACTUALLY helping them improve in their sport. That is part of the skill of being a great storyteller and knowing how to create context for your work in the gym.

A word on storytelling:

We have all heard that the best stories take you through an emotional experience, and if you’ve ever learnt sales technique you will be taught that people buy based on emotion, how the product you’re selling made them feel. S&C coaches are also salesmen and women because like it or not, at some point we need to get BUY IN.

In this case I wasn’t expecting Anthony to make the rugby player feel emotional about squatting!!! But I wanted him to connect the work he was doing in the gym with his PASSION for Rugby- by educating him how each exercise was going to help him perform better at Rugby.

I’ve asked permission from this coach to share this story as we did a great job of handling the situation and I thought it might give a good practical example in case it happens to you.

What did we do?

The first thing I did was share the email from the parent to Anthony- and let him know that we have had some feedback and we need to manage the situation.

For your information this was a teenaged boy who plays Rugby and sees Anthony for 30 minutes once a week.

The programme was based on picking a different theme each week which was the main athletic skill focus for 15 minutes (be it sprinting, change of direction, plyometrics) and a 15 minute strength section in the gym.

My email to Anthony:

”A parent has suggested that her son’s session is not individually tailored to her son’s needs. She has commented that he has been doing sprinting outside, crawling and other activities. If he is going to keep doing ‘general’ fitness, then she would rather not continue with the S&C, as he already doing general fitness in school sports. She commented that she thought he was going to be focused on lifting weights to get him stronger for rugby. He did 15 minutes sprinting with you, and then he did more sprinting when he went and did his training later in the day.”

I’ve had a look at your programme and it seems fine. Parents will always be concerned that sessions are sport specific and individualised. The secret is in the story telling and showing how what you are doing is linked to their sport.

Have a think and get back to me. I suggest you draft an email reply and I’ll look over it before we sent it to the parents.”

Anthony gave me a call before he drafted the email and I said that he should write a little sentence on each exercise to explain a) why it was chosen and b) how that will help with Rugby performance

I also said that because he only has 30 minutes we should go for the fitness component that will give the biggest bang for our buck. The parent wants it to be a strength based weights session and I have to agree this is the best thing to do. I appreciate the intent- to give him exposure to a range of athletic skills including sprinting and change of direction- but unless the parent wants to invest more in his S&C let’s get some quick wins by improving his strength.

For the purpose of anonymity I have referred to the rugby player as [son]

Anthony’s email reply:

Dear [Parent’s Name],

I would firstly like to apologize [Her son] was dissatisfied with the session on Tuesday.

I would like to explain how I have programmed his current sessions and give the reasoning behind my choices. Additionally to this on reading your feedback I can make some changes to my initial plans for [son] to specifically target his desire to only work on a ‘strength’ component of physical development in the sessions he receives.

Session Plan for Tuesday 22ndJanuary

1. Crawl Complex – Bear, Crab, OT (focus linear, inclusion of transitions)

My explanation: Crawling is compound movement pattern which requires large muscular activation which within the short time I have to train [son] is a good way to begin the sessions as it has specificity to rugby. Crawling (in various ways) is a valuable way to increase loaded shoulder stability through large ranges of motion. This is influential in rugby in both attacking situations (hand offs) and in defence (tackling – due to impact on shoulder)

2. Turkish Get up (Derivative) – unloaded, medicine ball loaded, DB loaded (focus progression of load and limitation)

My Explanation:good exercise to use with athletes of low training age – compound exercise (focused around hip range of motion) + stimulates problem solving ability using the body, important foundation to have progressing onto heavily loaded compound exercises.I progress this movement by increasing Load, this causes greater trunk activation (initial movement) then during the standing phase requires increased leg musculature activation.

This exercise is applicable to rugby in various ways. Firstly strength of trunk muscles during dynamic movement, rugby requires large movements of the body, stronger trunk muscles allow for the athlete to hold optimal positions through the duration of a movement this links to decrease injury risk. Additionally rugby is a game which requires players to transition from standing to the ground (and ground to standing) regularly. This exercise allows athletes to learn and practise effective methods of transitioning from the floor to standing……

3. Hop & landing task (focus knee / hip – progression hop complexity; direction & distance Tuesdays session included multiple progressions of complexity)

This exercise trains absorption of force, this is a key attribute to improving running and jumping performance. Rugby requires players to change direction throughout the game at various intensities and this combined with the contact element of the game leads lower leg injuries to be common and impactful on performance.

This exercise enables athletes to be more robust to potential lower leg injuries as tolerance to force in the joint and muscular structures has increased. It also benefits performance in a task like outside foot cutting (in rugby known as a side step), this move requires the complete absorption of force and then to push in the other direction.

4. Broad jump / Broad jump with plyometric entry

The Broad jump is a good exercise to train power production at maximal velocities. It also teaches an athlete the technique of force production in a horizontal vector (a challenging skills to master), this quality links directly to sporting performance in rugby as it is critical to acceleration. Acceleration (0-40m sprinting) dominates the game of rugby in both attack and defence. In attack improving acceleration can help an athlete get over the gain line, arguably the most important aspect of attack.

Additionally to the broad jump, a progression I have added is the introduction of a plyometric start. This has a training effect – improve force production when ground contact time is short, Also improves tendon stiffness which impacts on power production at maximal velocities, both of these being impactful on acceleration.

From a teaching perspective introducing plyometric activity enables me to progress [son] to move onto more complex plyometric activities (repeating broad jumps and bounding activities).

5. Squat, decline Press up, Reverse lunge (Sand Bag Loaded – front loaded)

This circuit is a combination of key movement patterns, I have implemented this to ensure [son] has mastered the safe technique and strength to move onto using more complex strength exercises

It was my aim to start to progress him to more advanced method within the coming weeks.

Now to explain how and why I chose to load these exercises using a sandbag – as a sandbag is an odd object it requires increased muscular activation around the active joints during a lift. This is not only a great method to give the athlete the required strength to progress to heavy loading through the use of barbell exercises. It also directly relates to rugby as these exercises increase the ability for the player to train for longer periods of time, increase injury robustness during their playing time and also

Front loaded to increase intensity (load is further away from centre of mass) – additionally front loading means squat becomes knee dominant exercise – links to acceleration and robustness to lower leg injury

-

- Kneeling start

- Standing start (split stance

Sprinting is a complex activity where small technique changes can have a large impact on speed, sprinting is categorised into either acceleration or top seed, as acceleration is more impactful on rugby performance I have chosen to use it in my training programme for [son].

I am skilled and experienced in coaching sprinting mechanics and have determined that this is an area [son] needs to improve on to be more successful at rugby. So my session on Tuesday was focused on body lean, foot carry through and head position in the initial steps of acceleration. This is why I made [son] do multiple sprints from a kneeling start as it is the ideal position to teach these technical points.

As rugby is played in a standing position, acceleration mechanism need to also be practised from standing positions, so during the session I progressed [son]from a kneeling start position to a standing start position to be more specific to his rugby.

Information about the structure of training

I am rotating between session focuses on a bi-weekly basis. My reasoning behind this is I have only got 30 minutes to work with [son] a week and at this stage in his maturation it is beneficial to expose him to the largest variety of fitness components as possible. So using a bi-weekly system I can increase the training stimulus he receives to multiple attributes.

Programme changes to allow [son] to train the desired fitness quality

Now I have explain the Tuesday session and the use of a rotation system I would like to explain my Solution to [son’s] current dissatisfaction with the training from Tuesday’s session.

From the email feedback I have read, [son] would like to solely work on a Strength component of fitness. I agree this is an important part of playing rugby, which is why it is included in my rotation of training stimulus’s for [son], but I will now use this as my sole focus of the programming.

My plans is to train [son] in lower body strength, which correlated Acceleration and upper body strength which is correlated to the level of rugby the player reaches.

The exercises which I will use as key performance indicators are the trap bar Deadlift (high handles) and the bench press, for lower and upper body strength respectively. Both of these exercises are commonly used in research as valid methods of assessment. Therefore they will be used as the main focus of the new programme and I will use a combination of other exercises to further improve the performance of [son] in these two performance indicators.

Both of these are free weight resistance exercises. I am an expert in the coaching and application of free weight resistance to improve strength and other strength qualities. I am more than capable to implement this style of training within his new programme.

The effective use of free weight resistance exercise is built on excellent technique and focus during lifts, these qualities are earned not given and it will require [son]to be dedicated to the gradual process which is free weight resistance training.

I believe this solution to [son] dissatisfaction is the right way to take his training and to use the 30 mins sessions effectively each week to meet his needs

What did the parent say?

She was really appreciative of the feedback and was able to understand how the original plan was in fact supportive of his Rugby. She was also happy to continue on the basis that her son was going to focus the 30 minutes on strength training.

This was a good result for APA and enabled us to move forward with a potentially unhappy client. The learning for Anthony, and for any of you reading this is that you need to be doing the selling from the beginning and storytelling to show how what we do in the gym connects with their sport- which is their passion!

I wanted to share Anthony’s email because I thought he did a fantastic job of explaining how each exercise supporting the boy’s Rugby development.

Anthony Hunt Biography

Anthony is an APA Strength & Conditioning coach as well as an Intern S&C coach and Sport Scientist at Middlesex County Cricket Club.

Anthony has a Bachelor of Science (BSc) Sports and Exercise Science from Oxford Brookes University ( – University of Edinburgh ( –

Where I am next presenting?

Speed, Agility & Quickness for Sports Workshop

Date: 24th Feb 2019, 09:00AM-13:00PM Location: Gosling Sports Park, Welwyn Garden City, AL8 6XE

Book your spot HERE

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM