This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 212 – Boo Schexnayder

Boo Schexnayder

Website: www.sacspeed.com

Background:

Boo began his career as a high school mathematics teacher as well as the American football and track coach. He eventually gravitated into collegiate track and field, and upon his first retirement in 2007 began Schexnayder Athletic Consulting. He recently returned to LSU as the strength coach for the track and field programme.

Discussion topics:

Boo on how being a school teacher set him up well to be in front of a group.

”Ultimately the most important coaching skill is communication. I think having an education background is a bit of an advantage in that regard.”

Boo on whether you can teach communication or it’s something that comes naturally

”I think both. I think most teachers have an aptitude and personalities that enable them to gravitate towards success in those areas, but I do think it can be developed And I think probably the single most important thing is confidence. Once you become confident in what you say, then you become comfortable in front of people. So my advice is to really learn your stuff, and the confidence that you get from that will definitely improve your ability to communicate with athletes.”

Boo on his philosophy related to plyometrics

”They are very important as far as the skill teaching as well as the power and elastic strength development that they produce. Plyometric training should be of very high quality, not a quantity base but a quality-based approach. Every different type of plyometric has a unique purpose.

Plyometrics are tremendous motor educators in that they teach you how to apply forces to the ground in certain and very precise planes of movement. If you hit the correct ratios of horizontal to vertical types of work, I think that you see not only strength and speed and power levels increase, but I think that you also see general movement quality increase.”

In Place Jumps:

- Typically done in circuit form

- Three or four different circuits that are used depending on level of athlete/time of year

- Best way to establish your plyometric volume

A good circuit might have 10-12 different exercises (note that his jump circuits tend to have 6-7 exercises in whereas his medicine ball circuits have 10-12). Each of those exercises is stressing the hip, knee, and ankle in a different way. Since the number one cause of injury, typically, is repetitive movement, because of the fact that you are picking all of these different exercises, you have zero chance of repetitive movement injuries when you use in-place jumps to build your volumes.

Short bounds:

- High technical demand

- Can be horizontal or vertical

- Primary purpose are skill producers

- 70-120 contacts

”In addition to the power and elasticity that they develop, these are the jumps that actually teach athletes how to apply forces to the ground correctly.

”They teach the correct timing of the ground contact forces that are involved in jumping activities. Therefore they have the most carryover, in my opinion, to skill, more transfer to sports skills than any of the others that we see.”

Extended bounds (Advanced):

- Very similar to short bounds

- But done over greater distances, 30-40 metres or so

- 250-450m total volume

- These are about power sustenance

- Applicable to sports with high power output but also a pseudo endurance demand

”They fit really well into the middle distances in track and field, and sports like basketball where you have these two minute spurts of play.”

Depth jumps (Very Advanced):

- Very high intensity training for athletes that are prepared for it

- Bouncing on and off boxes doesn’t necessarily make it a depth jump!

- Boxes need to be very high to create a high enough impact level

- Very short and sweet

Boo on the ratio of vertical to horizontal jump training

”I try very hard to maintain certain ratios of vertical to horizontal work. I typically find that athletes gravitate toward more effective movement patterns if you work vertical to horizontal at a ratio of about 2 to 1.

”I can’t really explain why that is. I think it has a lot to do with just human anatomy, and we’re kind of horizontally orientated creatures, I guess. if you look at animals who run around on all fours and you look at the human hip, there are still some vestiges there, similarity in the anatomy.

Anecdotally I found that it’s much more difficult and takes more effort to develop the vertical qualities as opposed to the horizontal qualities. If you’re accelerating there’s a very large horizontal component therefore horizontal multi-jump type activities are advised. On the other hand if you look at maximal velocity sprinting, the forces are more vertically orientated.”

Boo on the use of Plyometrics in Team Sports

”I typically don’t drop below my 2 to 1 marker even in team sports because I feel vertical plyometric activities are really helpful when it comes to change of direction. I know they don’t really look like it, but I think that the muscle groups that are responsible and effective in change of direction are similar to those we see used in single-leg vertical jumping. I always see change of direction as a yielding type of activity.

If you’re doing a box drop jump or a rebound jump off a box, well, you’re changing direction from down to up. At the tissue level, there’s really no difference in changing direction from down to up or left to right. It’s about yielding, and vertical plyometrics seem to be the environment where we can teach yielding best”

Boo on his principles around programming of plyometrics in the week

”You handle things very differently in-season versus out of season.”

Out of season– I like to include some type of plyometric component every time they do a speed power-based type of workout, which will be around two to three times per week. Early off-season you will establish your volumes with in place jumps, then you have your short bounds and finally you move to your advanced forms of plyometrics like the extended bounds or possibly the depth jumps.

In-season– Once you move to in season all rules are off and nobody is smart anymore. Once athletes start travelling and they have aches that come from competition you never know quite what you’re going to get. The competition season produces a very unpredictable environment and I think a good strength coach becomes more reactive at that particular time of year.

I would (ideally) like to have them perform high intensity plyometrics in-season every 10-14 days. There is no sense in doing low-end stuff if you’ve already prepared them to do the high-end stuff. But at the same time, I know that sometimes the demands of competition, that might not be realistic. Of course, the sport itself has something to do with it. If you’re a basketball or volleyball player and all you ever do is jump, well, how many plyometrics do you really need?

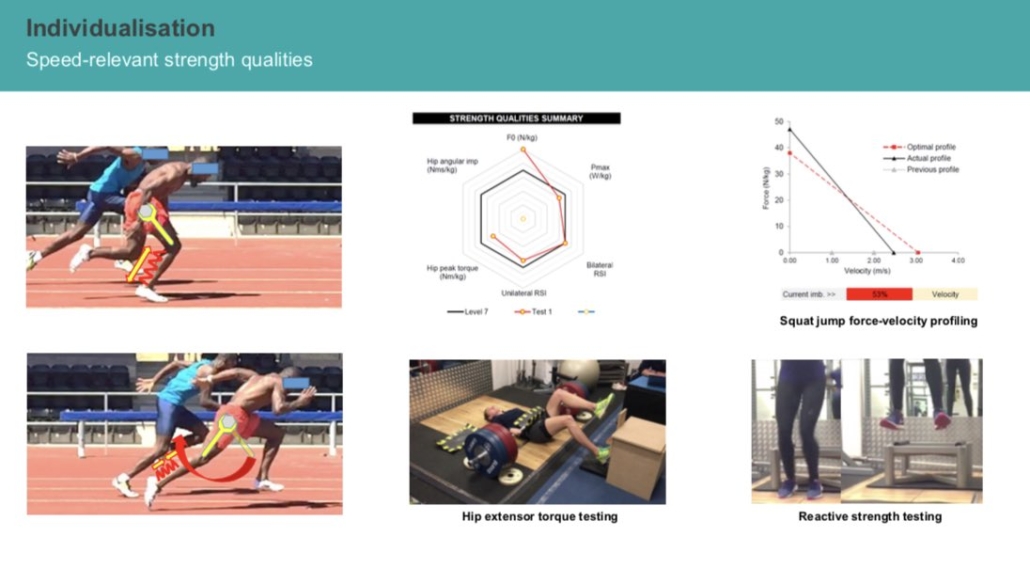

Boo on some of the technical trends in coaching maximal velocity including where he thinks people are spending a lot of time where they shouldn’t be!

Arm action– ”In sprinting coaching you’re basically teaching people how to push against the ground correctly. The upper body counters and balances the movements of the lower body. I think that generally speaking in coaching we do not trust the body’s movement organisation processes enough. A lot of our sprint movements are organised subconsciously, they come from the spinal cord, not from the brain. when you cut the chicken’s head off, it continues to run around the yard. So obviously you don’t have to THINK of everything!”

Because of the fact the arms are very visible, I think that they’re favourites to coach. But the arm movements evolve as the leg movements evolve, going from long arms pushing back during acceleration to short arms pushing down during top speed. There is also rotational components in sprinting, and when the hand moves back they should widen a little bit if the hips are oscillating and turning the way they should do.

Core Training– ”When you’re sprinting at maximal velocity, the demands on the core are so much greater than what you experience in a sit-up or a crunch or one of those simple exercises that is not really core training. When we examine what the core does in sprinting, we see that the shoulders and hips operate in opposition. You see a winding and unwinding action in the core, so our training needs to be rotational in nature, and specifically anti-rotational strength. This is where medicine ball catch toss stuff and things of that nature forces you to stabilise elastically in the core and it’s a very specific type of movement.”

Coaching the Knee lift– ”Knee lift is undoubtedly necessary in sprinting. When you lift the knee you place a pre-stretch on the hip extensors, and that enables a more forceful push against the ground. But we’ve got to remember the other side of it as well, once you push against the ground completely, you’re putting a pre-stretch on the hip flexors, and that helps to pump the knee.

In some sprint coaching cultures it’s gotten to the point where we are overdoing knee lifts so we’re forgetting about the pushing side of things. Sprinting is about pushing down, and I don’t want to base my basic sprint training or teaching model upon picking the feet up.”

Boo on his principles around use of circuit training for recovery

”For restoration purposes with almost all speed power athletes I use circuit training, basically body weight circuits, med ball circuits, and also some weight training circuits. Mild to moderate levels of lactate produce growth hormone responses that are very positive and assist in restoration. These circuits are typically about 12 minutes in length. I put the circuits together in ways where I’m trying to hit a perfect balance between really fatiguing them , but also allowing them to be powerful throughout the entire circuit.

I like the circuits much more so than (tempo) running. Some coaches like to use tempo running in search of restoration and view that they can achieve the lactate levels the same way with tempo training. It’s unquestionable, you can’t! But I’m going back to what I said earlier about repetitive movement. And if you do running workouts for your restoration, that’s just right, left, right, left, and that’s a lot of repetitive tissue assault.”

Author opinion:

Boo has extensive experience in the area of track & field and strength & conditioning, and it all started in the classroom as an educator which really helped with his teaching ability!

One thing that was interesting from listening back to the podcast, was his comment about confidence that you gain from really ‘knowing your stuff.’ The industry can do a better job in my opinion of ensuring that communication skills (and business skills) are put higher on the coach education agenda. Brett Bartholomew who has featured several times on the Pacey Performance is a coach who is blazing the trail here- with his Bought In and ValueED online training programmes.

It was also interesting to hear Boo’s take on circuits for restoration. In the Blog Review with Derek Hansen he talked about the benefits of tempo running done daily as a form of micro-dosing. So I guess you need to read both of their rationals and do what makes most sense for you. Who says you couldn’t do both? But I hear what Boo says about the repetitiveness of running! Some times if my Tennis athletes have had a hard day of tennis drilling the day before, the last thing they want to do is more running on their feet the next day!

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Learn Your Stuff– really learn your stuff, and the confidence that you get from that will definitely improve your ability to communicate

- Have a Classification System– Boo uses four main categories of plyometrics (in-place jumps, short bounds, extensive bounds and depth jumps)

- Maintain a 2 to 1 ratio– of vertical to horizontal plyometric work in your programme

- In-Season Programming– perform high intensity plyometrics in-season every 10-14 days

- Understand Key Technical aspects of Sprinting– Arm action, core training and Knee lift should be coached according to their intuitive function in sprinting.

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

www.www.sacspeed.com

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 367 Gareth Sandford

Episode 362 Matt Van Dyke

Episode 361 John Wagle

Episode 359 Damien Harper

Episode 348 Keith Barr

Episode 331 Danny Lum

Episode 298 PJ Vazel

Episode 297 Cam Jose

Episode 295 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 292 Loren Landow

Episode 286 Stu McMillan

Episode 272 Hakan Anderrson

Episode 227, 55 JB Morin

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 204, 64 James Wild

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 183 Derek Hansen

Episode 175 Jason Hettler

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM

=> Follow us on Facebook

=> Follow us on Instagram

=> Follow us on Twitter