This post is a follow up to my previous post on Periodisation- Part 1 which you can see here.

In this post I would like to share with you some of my recent thoughts on the topic of Transfer of Training. The holy grail of strength & conditioning in my view, is taking an athlete and training them so that the physical gains they make actually enhance their sports performance- this would be a successful transfer of training.

I originally came across some of the work of the old Soviet regime from looking at a great website all about the Canadian Athletics Coaching Centre which you can see here. It was here that I first had the chance to read articles written by authorities like Verkhoshansky and Matveyev. But I kept hearing about a coach called Dr. Anatoly Bondarchuk who was working with hammer throwers at the time and was applying his concepts of ‘Transfer of Training’ to his training methodology. I bought a book of his work in around 2009 but at that time it was not well translated from his native language and I felt I had an incomplete understanding of his concepts.

This also coincided with a chance discussion with Dr Mike Stone at the UKSCA Conference around the same time. He was a little critical of the statistics which Bondarchuk had used to determine the correlation between all kinds of different exercises and their effect on specific performances in an event. (Or at least that is what I took away from our brief discussion- as I don’t want to misquote Mike Stone!). Therefore I never really followed through in this area of my learning and for better or worse kept going with my training system as I understood it at that time.

So fast forward to the present day, April 2014 and I now stumble across the website of Central Virginia Sports Performance (click here) and his name amongst others comes up again, as well as Natalia Verkhoshansky who is continuing the great work of her father, Yuri. Now 5 years later their work is becoming more accessible thanks to the power of the web and better translations, so I figure it’s time to take another look.

For this post I just wanted to run down on my application of the concept of Transfer of Training and how it fits into the APA Training System.

Clarifying the Objective

As I already said above, I think the holy grail is getting outcomes where it counts…on the sports field. Natalia Verkhoshansky articulates it slightly better than me:

”The final goal of competition exercises in Olympic sports („Citius, Altius, Fortius‟ – „Faster, Higher, Stronger‟) may almost always be related to the capacity to express power produced by the speed of movements and by the force of overcoming external resistance.

Consequently, the training process, focused on improving the sports result, could be defined as the process of increasing the power output of competition exercise”

Every sports skill without exception can be thought of as a complex motor action which is created in order to solve a particular movement task specific to that sport. This motor action is often called the motor pattern (as it is usually the combination of separate motor actions) and sports coaches often refer to it as a ‘movement pattern’ when referring to the physical aspects of the motor skill. As it relates to the work of the Soviet researchers this motor pattern is called the ‘Competition Exercise’ or (CE).

Analysing the Competition Exercise from a Biomechanics point of view

Like any good S&C coach ought to do, a Needs Analysis will help determine what types of training are most suitable for the athlete in order to prepare them for their event or sport. It’s important to start with some basic laws of motion and look at Kinetics and Kinematics:

- Kinetics – is one of the branches of dynamics, concerned with what body movements are produced under the action of particular forces. Not to be confused with kinematics, the study of motion without regard to force or mass.

Analysing every competition exercise from a kinetics perspective, it may be assumed, that during its execution, not only are active driving forces being produced by muscular contraction, but also reactive forces, which are activated as a consequence of the impact of active forces with the external environment: We can break these forces down into:

– gravity force (body weight or its links);

– reactive forces arising as a result of the interaction between the active forces and the environment;

– force of body (or its links) inertia;

– force stored in the muscle-complex as elastic energy during the preparatory phases of movements.

Therefore, increasing the power output of competition exercise regards increasing the body’s capacity to generate enough active force to overcome the external and internal opposition which will enable the acquisition of specific skill to control the body movements.

Now I am definitely not going to get into the ‘How Strong is Strong Enough?’ debate in this blog. At this point I merely want to draw attention to the fact that we should be starting to work back from knowing what the competition exercise is that we want our athlete to be really good at and also understanding the types of forces needed to excel in it!!!

Increasing the Force Generating Capacity of the Body

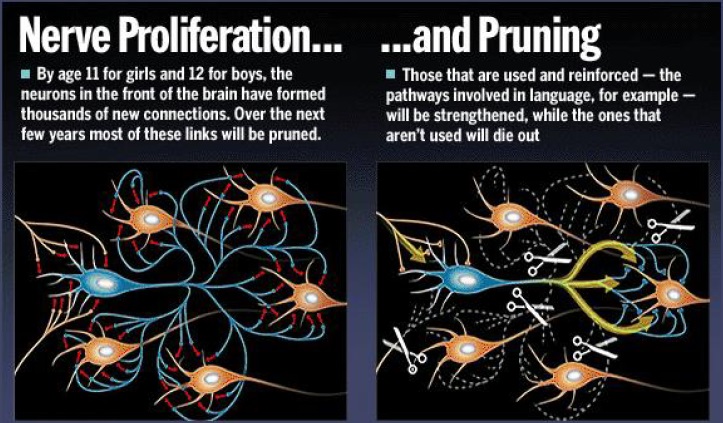

”To obtain a necessary kinematic characteristics of the complex motor action, the motor control system operates not at the level of single muscle, but at the level of innate functional components of the human motor apparatus, called working mechanisms, involving them in appropriate ratio to solve a given motor task.” Verkhoshansky, N (2011).

In basic terms this means that in order to prepare to produce the forces required during the competition exercise we need to train movements not muscles. Sound familiar? These movements can be sub divided by the different mechanisms of the motor control system they utilise:

- Muscular system- voluntary contraction of agonist and antagonist muscles to produce synchronised movements of body segments

- Muscular system- involuntary contraction of key postural reflexes

- Elastic properties of muscles – the force stored in the muscle complex as elastic energy;

The higher the functional level (force generation capacity) of the working mechanisms involved in a given competition exercise, the higher the athlete‟s motor potential, which determines his capability to execute this competition exercise with higher power output. What this basically means is that the more we can train the general functional capabilities of the muscular system the higher the power output potential we can achieve on a very specific competition exercise.

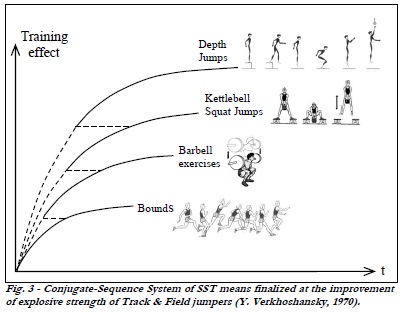

It’s now that we can start to discuss the terms ‘General’ and ‘Specific’ as they relate to the types of exercises we might want to use in the ‘Preparation’ phase. I deliberately didn’t want to talk about exercise categorisation in the last blog as this is a massive topic in itself. The best way I can describe the way I approach my training preparation phase is I start with a greater focus on general training means early in the preparation phase and increasingly focus on more specific training means as we progress through the preparation phase.

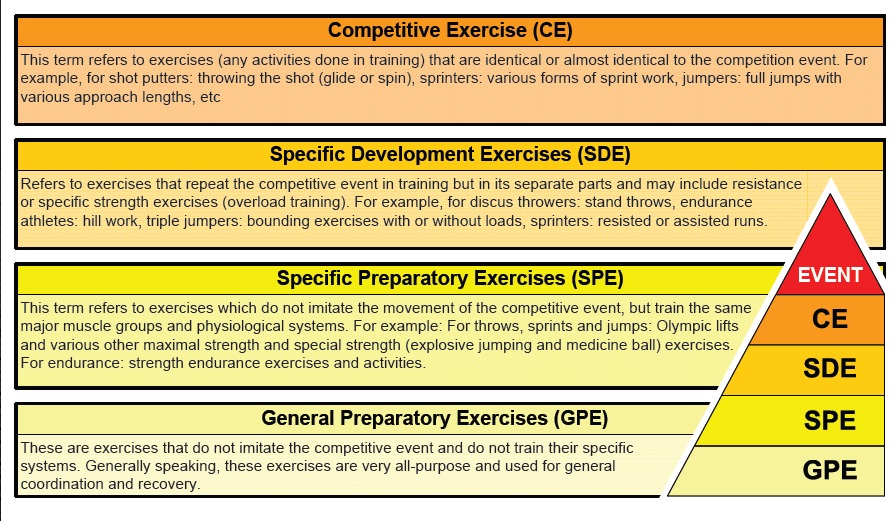

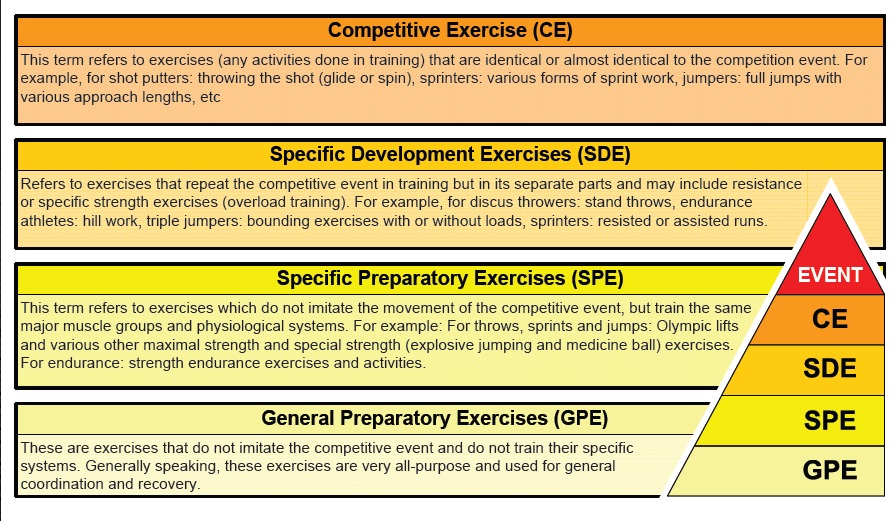

Track & Field coaches use the classification adopted from the Soviet researchers.

We can now start to think in these terms, starting with the end in mind and working back to choose the exercises that we need to start with. Using this concept most sports will have similar training means at the general level of exercise classification and they will diverge as the methods become increasingly specific.

As it relates to the APA Training System I like to group the classifications noted above under more simple headings:

- General or Specific

- Basic or Advanced

Typically the more General the exercise in nature the more ‘global’ the muscles that are recruited such as the large muscles of the quadriceps, hamstrings and glutes in the barbell back squat. The more specific the more ‘local’ the muscles that are recruited such as the upper fibres of the latissimus dorsi during explosive shoulder extension as would be performed in a weighted barbell pullover. I remember Calvin Morris saying he used to do this exercise with Steve Backley as part of his specific exercise regime for the javelin throw.

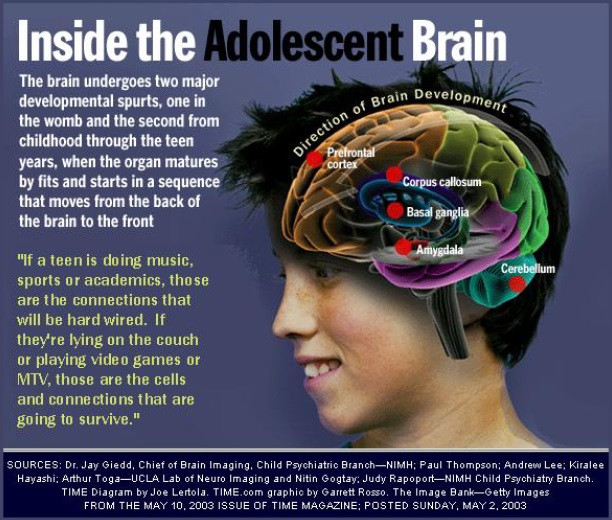

My personal reason for wanting to differentiate between Basic and Advanced exercises is because a General exercise can be a very high level exercise in terms of loading parameters but it just doesn’t have much relation to the competitive exercise. So for a very experienced Tennis player they might start with maximal strength back squats in their General Preparation. But seeing as I work with a lot of children I need to make sure my coaching team are taking into account the loading and if it is generally lower in intensity such as Hypertrophy work we will classify it as ‘Basic.’

Key point: Not all athletes will do Advanced exercises in their General Preparation.

If you would like to look at the terminology described above I would definitely check out the Canadian athletics Coaching Centre website and also have a look at a great website called ‘Complimentary Training’ by Mladen Jovanovic and a blog which goes into detail on these topics. Click here for a link to one of his blogs on this topic.

Increasing the Power of Key Movements

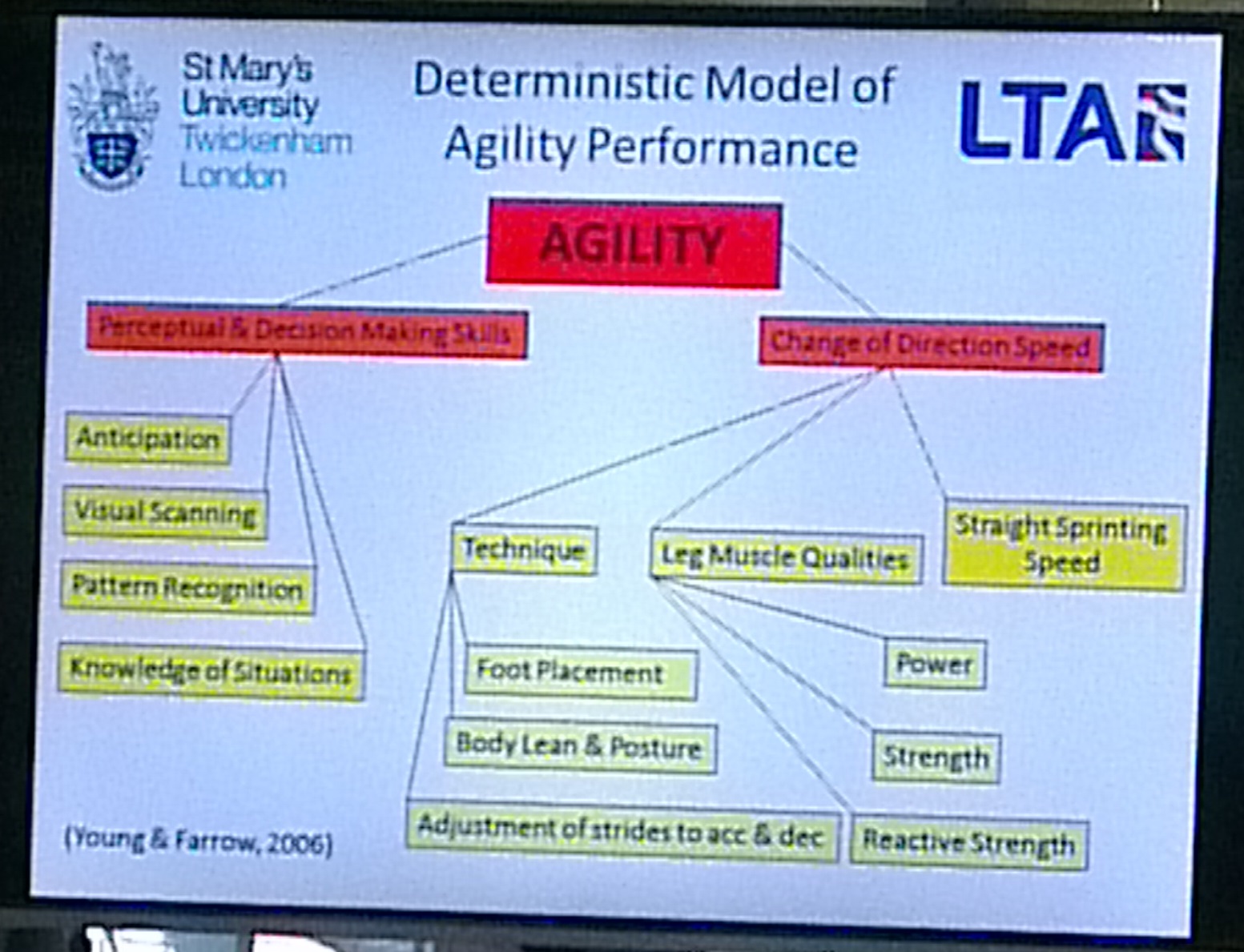

Now that we have set the scene for the importance of the competitive exercise we need to go back to the science. The different conditions under which the neuro-muscular system works during the execution of different competition exercises recall different mechanisms for assuring these changes. For example the main competition exercises for a jumper, a thrower, a sprinter, a middle distance runner, an MMA athlete, a tennis player and a soccer player all place different demands on the body.

These mechanisms are related to the activation of different functional characteristics (options) of the neuro-muscular system (motor unit recruitment, motor unit activation frequency, motor unit synchronisation and others), which are usually associated with different strength capabilities.

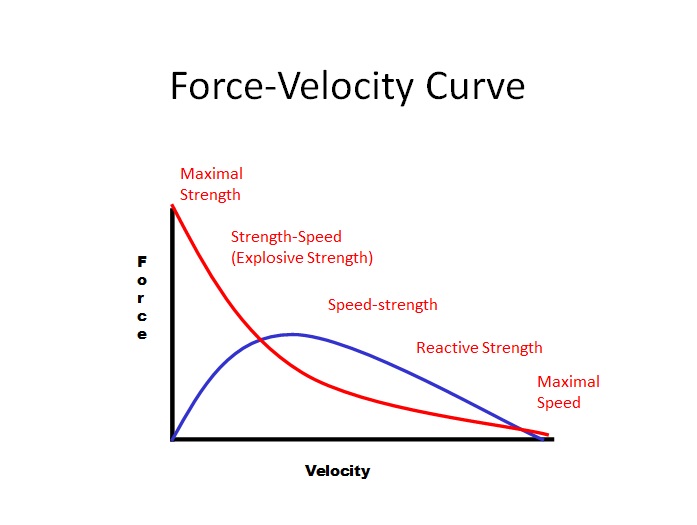

The basic forms of these functional characteristics can be identified as basic strength capabilities:

- Maximal Strength (P0) – the greatest magnitude of the voluntary force-effort, which the athlete is able to display in isometric regimes when there is no time limit to complete the task

- Explosive Strength (J) – is characterized by the athlete‟s capability to achieve maximal force-effort (FMAX) in the shortest time (TMAX): J = FMAX/TMAX.

- Starting Strength (Q) – is characterized by the athlete‟s capability to produce rapid increases in force-effort at the start of muscular tension. It is measured by the so called Starting Strength gradient: S-gradient = F0,5 MAX / T0,5 MAX).

- Accelerating Strength (G) – is characterized by the athlete‟s capability to rapidly achieve the maximal value of force effort (FMAX) in the final phase of muscular tension. Usually, it is measured by the so called Acceleration Strength gradient: A-gradient = F0,5 MAX / (TMAX – T0,5 MAX).

Verkhoshansky explains that ”In movements executed with different levels of external opposition the basic strength capabilities do not have equal relevance in obtaining the highest power output of the competitive exercise.

For example, when the force-effort is displayed in high speed movements with a small external resistance, its magnitude is determined by the so-called High-Speed Strength (Fv), strictly correlated with Starting Strength (Q). As resistance increases, Explosive and, after, Accelerating Strength become more important.

Basic strength capabilities expressed in different regimes of muscular contraction usually require activation of different functional options of the neuro-muscular system. For example, the capacities to generate maximal force in isometric and dynamic regimes of muscular contraction are assured by different neuro-muscular mechanisms, which are relatively independent of each other in their functional display and development.

Also the capacities to generate force in overcoming (“concentric”) and yielding (“eccentric”) regimes are related to different neuro-muscular functions: “The greater cortical signal for eccentric muscle actions suggests that the brain probably plans and programs eccentric movements differently from concentric muscle tasks.” (Yin Fang et al., Journal of Neurophysiology, 2001, vol. 86 n. 4).”

However, an important consideration to keep in mind is that sports movements are usually executed in a mixed regime of muscular contraction.

For example, during a single explosive movement in which the athlete has to displace a heavy load from a standing position, before initiating the movement, the muscles work in an isometric regime (e.g. shot putt). As soon as the developing isometric force-effort achieves the level of the opposite resistance force, the movement starts and the muscles begin to work in the dynamic regime.

In the so-called ”starting movements” executed without a ”countermovement” against heavy resistance (for example overcoming the body’s static inertia), the major role is played by Maximal Strength (Po) and Explosive Strength (J), expressed in an isometric regime (e.g., Power lifting and Olympic weightlifting).

When the explosive movement is executed with a ”countermovement”, i.e., in the reversal yielding-overcoming (“eccentric-concentric”) regime, the major role is played by Explosive Strength (J) expressed in the overcoming (“concentric”) regime.

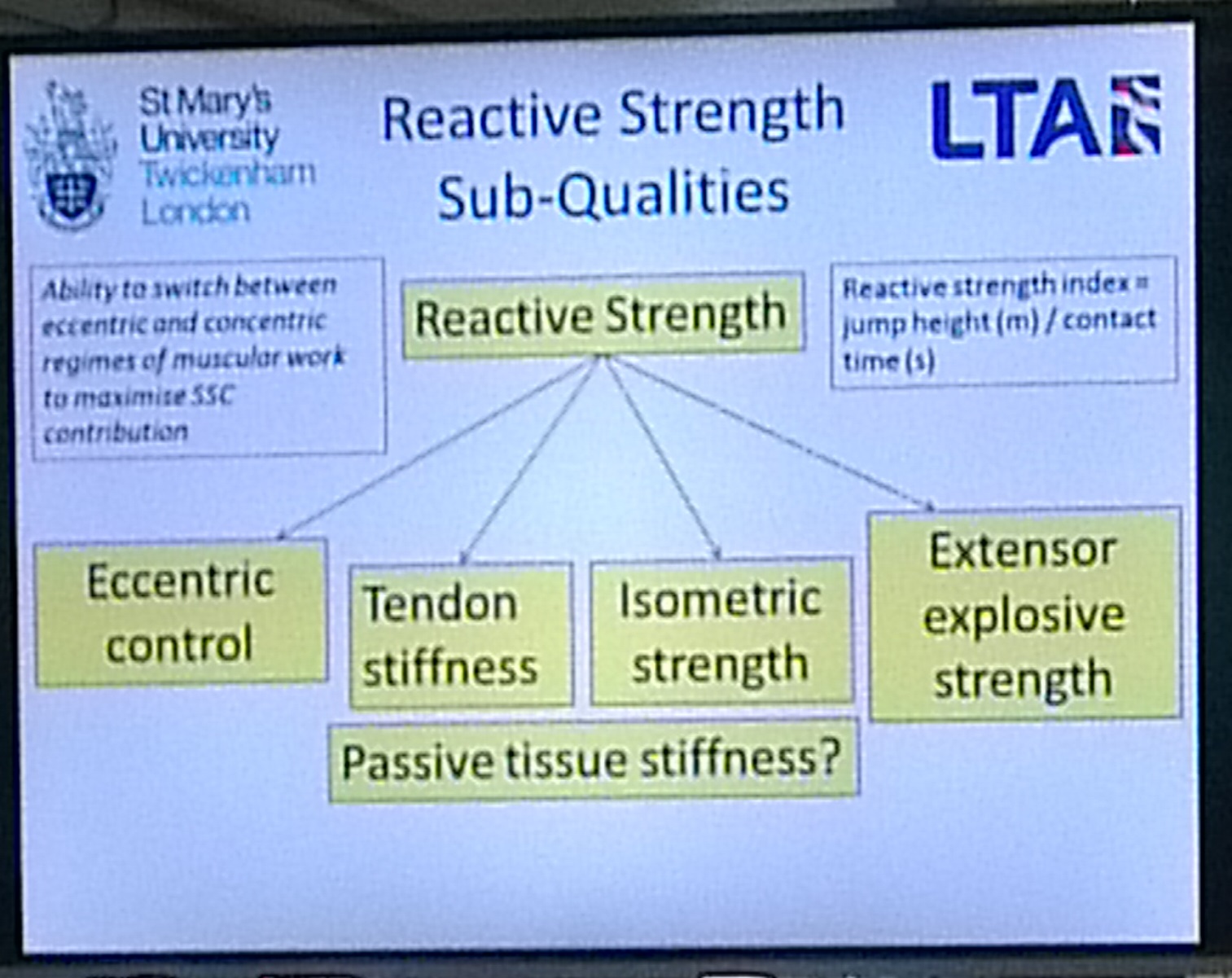

In reversal movements, executed in the rapid transition from the yielding (“eccentric”) to the overcoming (“concentric”) regime, two other functional characteristics of the neuro-muscular system are used: the Reactive Ability of the neuro-muscular system ( the capacity to develop the highest value of force in the overcoming phase due the stimulation of muscle proprioceptors during the yielding phase) and the Elastic properties (potential) of muscles (which provides an extra source of energy assuring the enhancement of the subsequent muscular contraction.” These would be more associated with methods used with runners such as drop jumps and methods that have a very short ground contact such as repeated hurdle jumps.

Therefore, to reiterate the original point, different training means, used together in the training process can elicit an integrated functional adaptation (Cumulative Training Effect), using a pre-determined combination of different means.

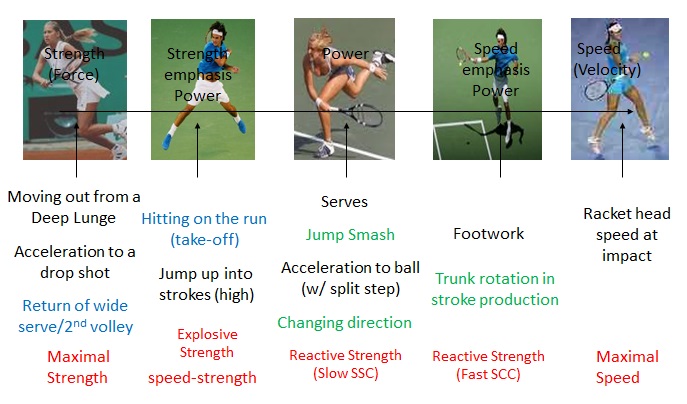

How does this apply to Tennis?

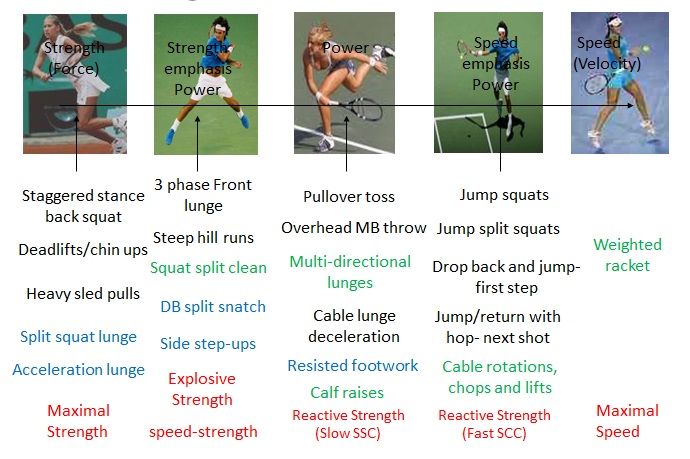

Clearly Tennis places a wide variety of demands on the body. At first glance you might think that because the Tennis player is working against a relatively insignificant external resistance (tennis ball) that there is no need to do ANY explosive weightlifting exercises at the higher end of the Force-Velocity spectrum (Olympic lifts at >70% 1RM); they should just lift everything light and fast.

But one of the things I learnt from reading Verkoshansky’s work is that ‘impact’ forces are extremely high and some of the explosive movements in Tennis, especially when returning wide serves and flat out running out wide do place significant load on the body which we must prepare for. It’s not just as simple as saying that because they only have to overcome their own body mass and that of a tennis ball that they don’t need to work against any significant loads!

Below are some of the different examples:

- Maximal Strength: when overcoming the body’s own inertia and when absorbing the massive impact forces from landing during flat out running and take off

- Explosive strength: when applying a hard impact into the ground in order to ‘take off’ the ground during a powerful ground stroke using the ‘power step’

- High Speed-Strength: during the majority of high power tennis shots when hitting the ball!

- Reactive Ability: use of the stretch-shortening cycle during rapid push off when changing direction

- Reactive Ability: use of the stretch-shortening cycle during the split step with a rapid counter movement

Summary

My summary of this blog is that you need to know your sport. You need to know what the competition exercise or exercises are and you then need to plan appropriate training methods that will enhance the physical mechanisms that will overload and subsequently improve performance in these skills.

In the final Blog post on periodisation coming next I will attempt to analyse the competitive exercises needed for Tennis and the most appropriate training methods for these.

In the mean time I highly recommend you check out the two books below. The ‘Secrets of Russian Sports Fitness and Training’ is an easy read and you can blast through it in a day. The Special Strength Training Manual,’ is equally compelling but it a bit more in depth and would definitely need a bit of background understanding of training theory.

Hope you enjoy the post.

Remember to visit us online HERE for more updates on our latest workshops and qualifications.