Pacey Performance Podcast REVIEW- Episode 266 Hamstring Injuries- Part 2 of 2

This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 266 – Hamstring Injury

Jurdan Mendiguchia

Background:

Jurdan Mendiguchia– Physiotherapist, Researcher and Injury Consultant. Jurdan is a World expert when it comes to injury prevention and rehabilitation, particularly in hamstrings and ACL. He has 40+ research papers to his name (see link above to Research Gate).

Discussion topics:

JM on the current approach to hamstring injury rehab and prevention and how would you say there is room for improvement in this area

”Good question. The issue of hamstring injury definitely needs a new boost, a step forward. I think it has been an injury that contrary to other types of injury such as ACL, has been approached from a very analytical and isolated point of view. This influences the intervention carried out.

To give a clear and simple example, in the ACL injury, inciting events such as jumping and side cutting were biomechanically analysed to later analyse how the trunk, hip, ankle or even anatomy influence this inciting event providing a multifactorial approach to the problem. Consequently injury prevention programmes have been directed to correctly and repeatedly perform the movement related to the injury mechanism such as side cutting. I never see a guy only perform squats to prevent the ACL injury!

Everything was reduced to the action of the hamstring at a specific time of sprinting, the main injury mechanism. And from there the measurement methods such as isokinetic and eccentric (Nord board) and prevention training arised. It has been focused at that concrete moment without going too deep into how the trunk, pelvis, the other leg interaction influence that moment. Unsurprisingly that was extrapolated to the prevention methods, and most of the research methods have focused on improving the specific strength or isolated strength of the knee flexor without knowing which exercises activate one hamstring muscle or the other!” (rather than the correct performance of the movements related to the injury like in the ACL!)

If we go the literature we can see a huge difference between the articles dedicated to the nordic and sprinting, at least in the injury related area. I wonder myself, since it has been more than 18 years since the first study carried out in the AFL that suggested that eccentrics are effective in reducing this type of injury. So it is not a new thing, and at least in the major leagues all the football teams I know are doing eccentrics at least weekly. And what is still the biggest injury problem today? Hamstrings!

We can assure ourselves in the knowledge that the velocity and intensity of the game has increased but then maybe eccentrics are not effective enough to battle against actual player demands.

We cannot ignore what is happening and continue to not listening to the concerns of the coaches of the teams frustrated and under pressure because they continue with the same injuries despite using eccentric exercises. What has been suggested does not solve, at least entirely, the problem.

Without criticising what we have done in the past, we need for sure, something else. If we can agree that it is a multifactorial injury, and the factors interact with each other the current force or range of motion measurements and isolated measurements are not able to show us these associations.

Therefore everything goes through the development of new ‘contextualised screenings’ that allow us to decipher the primary factors to correct.

When we talk about context we are talking about the main injury mechanism, that is none other than the sprint, and of course it is not the only injury mechanism as there are injury mechanisms related to overstretching, trunk perturbations etc.

If we want to be more close to success and succeed from a injury prevention perspective at least in football, in my opinion we need to perfectly know our sport demands and delivered adaptations and our coaching methods and training.”

JM explaining the role of the trunk and pelvis when it comes to hamstring injuries.

”It has been shown that anterior pelvic tilt is a risk factor for hamstring injury, if we only base it theoretically on elementary anatomy, we know that the hamstrings attach to the pelvis at the ischial tuberosity. An increase in anterior tilt will increase hamstring length.

Risk Factors

- Anterior pelvic tilt (related to bicep femoris)

- Increased Trunk and Hip Flexion (Functional MRI shows it increases bicep femoris signal intensity). Sprinting with inclined trunk there is more bicep femoris lengthening mostly at the beginning of the acceleration phase

- Interaction of one leg with the other- the pelvis is the only joint that connects the legs

It has been shown that to run faster you need a deep anterior pelvic tilt. But the mismatch is that while it could be good to run fast like in track and field and soccer, but if you go too far it can be dangerous from an injury perspective.”

JM on the focus on knee flexor strength rather than the multifactorial issues around sprinting

”The thinking process is not bad because it was hypothesised that late swing phase is where the injury probably happens. It is true that it is the moment where the hamstring acts as an absorber doing negative work in order to prevent the tibia going away. So yes, we focus on that and probably generally speaking it is good.

But at this same moment the anterior pelvic tilt happens, ipsilateral gluteus maximus force happens, contralateral iliopsoas lengthening happens. So if you look at the entire movement you can see all this happening concomitantly (next to each other!).

I don’t know why we focus only on that (knee flexor strength). In fact we see that there is no relationship between isolated testing and mechanical properties of sprinting. That makes sense to me as the function of the biarticular hamstring muscle is totally different to what we are doing when we test in isolation.

If you compare the cross sectional area of a football player’s quadriceps and hamstrings with a non player, the quadriceps are equal but the hamstrings are greater. But when you normalise with knee extension or knee flexion strength, it is less in football players. This is probably because we are not testing how this group of muscles are functioning during sprinting.

We know that footballers have greater cross sectional area which means probably they are stronger, but when you normalise and measure knee flexion during isokinetic movement you have less hamstring compared to people who don’t do football.”

JM on injury prevention methods he would use if he was working in a Football club full-time

”This dichotomy of sprint versus nordic that is trending is totally wrong, and also dangerous.

Consider the this case study of an elite coach considering increasing stride length with a sub 10-second 100m sprinter to increase performance.

You need to be structurally prepared for the task that your coach (or the game) demands.

Therefore if his structure is not prepared to run in that way, he can have all of the strength in the world, but if you don’t correct his structural issues sprinting in that new way with the increased stride length for him it would be harmful. Sprinting is not the new injury recipe either. If the athlete is not prepared to run properly or does it wrong in terms of shape or volume the sprint will become counter productive 100%.

In fact, in football sprinting has become the new nordic. If you hear coaches right now, they will tell you that you are old school if your players don’t sprint. I think that’s not the right way to think. If from your screening methods you interpret that the cause of your player’s injury is a decrease (lack) of strength, either from the hip or knee, the prescription of a strength programme in the gym will be adequate for sure.

But therefore the answer to your question is almost always, ”it depends.” Do not apply anything as a recipe or established protocol. Look what your athlete needs, because if not, as many people do, we can treat people by email or twitter without seeing the patient!”

JM on the use of the nordic in hamstring injuries

”The use of the nordic for more than 20 years has shown positive results, in relation to hamstring injury prevention. Therefore we can say that as a general measure it seems that it has turned out to be advanced in it’s day. But I wonder if right now it’s enough, according to the training methodology that is undertaken by most of the football teams that contain eccentric work in their programme and looking at the current epidemiology data showing no injury reduction.

I wonder too, if a single exercise satisfies the individual and multifactorial needs of the individual and the pathology.

Another thing in relation to your question, is the reason why eccentrics and the nordic exercise in particular is effective, because consistently too it has not been proven the prediction ability between eccentric strength level and injuries.

But it is true that there are architectural adaptations to eccentric strength such as:

- alterations at the aponeurosis level

- change in extracellular matrix with increasing collagen

- change in protein isoform

- dynamic pennation angle increases (to protect fascicle from lengthening)

- tendon stiffness (increase in tendon compliance during sprinting results in a decrease in musculotendinous length).

A fatigue provoking protocol after eccentric exercise decreased tendon compliance and increased fascicle length and this can be related to different role of the tendon being compliant at low loads and intensities but acting as a force transducer and stiffening structure at high loads and highs. No one as far as I know has analysed that after an eccentric strength intervention.

It is true that lately much attention has been paid to Fascicle Length as a possible injury protection mechanism to explain the positive effect of the nordics, with respect to hamstrings. It has been suggested as a risk factor in football despite having a low association. Theoretically, the idea is based on a hypothetical increase in sarcomerogenesis after eccentric work. This assumes that the addition of sarcomeres in series in humans after eccentric exercise will protect the muscle from damage.

However, although theoretically supported I think that today with the technological knowledge we have with it is hard to demonstrate the relationship between fascicles and hamstring injury.

There are technical limitations on fascicle measurements. We know too, that hamstring architecture changes throughout the muscle and only one region is measured. ”

Moreover, the measure is static, so we are assuming that what we are measuring statically will happen dynamically, without considering muscle tendon interaction and behaviour.

JM on role of ‘activation’ work and its role as a risk factor for hamstring injury

”In one prospective study no association between muscle activity and hamstring injury during isokinetic measuring was found. But in contrast another study showed prospectively too, doing a prone hip extensor extension manoeuvre, a delayed hamstring recruitment compared to erectors in those players that after suffered an injury, with no difference in EMG amplitude at all.

Another study showed an association between decreased EMG activity of gluteus and trunk muscles and hamstring injury in a prospective study of football players sprinting overground. (prospective definition- likely to happen at a future date). But in terms of hamstring activity there was no association between EMG of biceps femoris and hamstring injury during follow up was found.

There is still equivocal data in the research comparing the reduction (or not) of bicep femoris EMG activity when comparing injured to non-injured leg, with some studies showing differences and others not. But they use different techniques such as functional MRI and EMG, so it is difficult to compare because the physiological processes behind them are completely different. There are also differences in the type of exercises used.

There could be something there, but we know at this point that EMG has limitations, it neglects regional hamstring activation, it has high variability and there is an inhibition during eccentric contraction and we have to account too for crosstalk.”

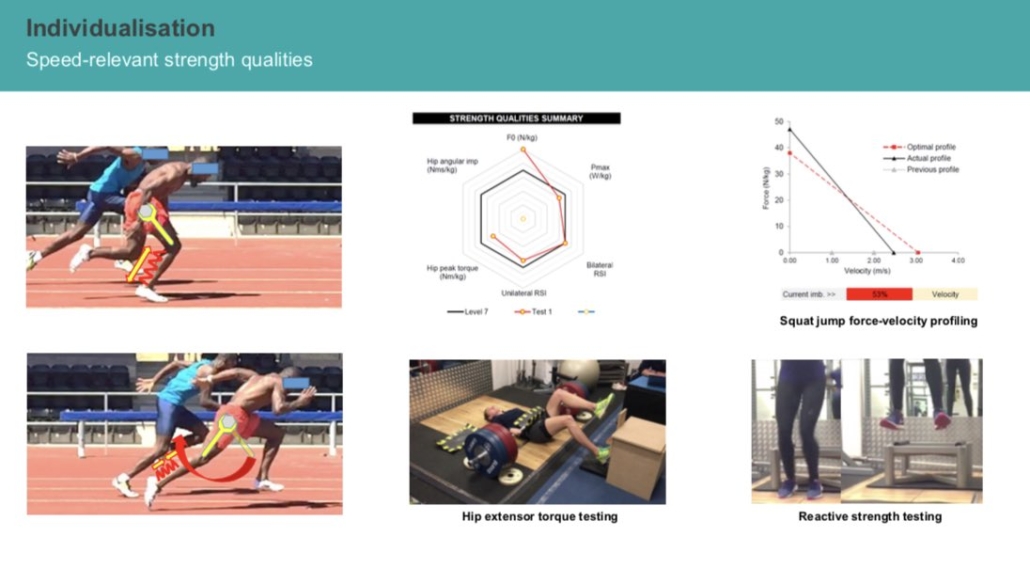

Individualisation of Hamstring Recruitment Profile

”Concurrently in hamstring muscles, the distribution of activation and the distribution of torque generating capacities varied greatly between individuals during a maximum knee flexor task on an isokinetic dynamometer. Moreover, significant negative correlation was observed between the imbalance of hamstring activation muscle and the time to exhaustion.

This individual variability is not in isolation and has been confirmed in other muscle groups. Regional EMG patterns are highly individual, and each individual maintains similar proximal to distal and inter-muscular EMG patterns across different running speeds.

This confirms the idea that activation sequence and patterns are very very individual and that has made me wonder if the hamstring pattern is so individual, is there a gold standard?

- How much can we rely on previously conducted studies knowing the variability between people?

- Will it be necessary to change the pattern of activation after the injury?

- Will it be as easy as changing the activation pattern during running and prescribe a hip dominant or knee dominant exercise?

With these questions I don’t mean that EMG pattern is not related to hamstring injury but we have to question things and we have to move further in this field to give more rigorous advice and opinions.

Currently there is not a gold standard, we don’t know if it is good or not to change the patterns of people after the injury has happened.”

JM on use of Isometrics in Hamstring injury reduction training

”I know that there is a debate about the isometric or eccentric behaviour of the fibre at the time of the injury. It looks clear that towards the end of the swing phase during sprinting the hamstring muscle-tendon unit lengthens and the hamstring forces increase. But what about the muscle fascicle or fibres? Do they increase because the muscle is stretching, or decrease because of the force and activation increase?

I don’t think that anybody knows for sure right now!

Both visions (isometric and eccentric) share the idea of the inability of the fibres to withstand the mechanical forces imposed during sprinting.

If you want to reproduce the injury mechanism and the same behaviour and same adaptation to the muscle tendon and fascicle don’t jump between isometric and eccentric contractions- simply run!

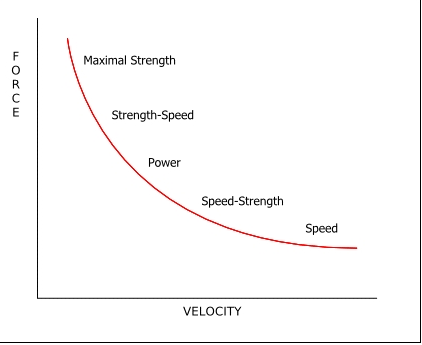

But more relevant and important than the type of contraction is the time and velocity of the contraction depending on the effort that we want to create at the muscle tendon junction.

We will choose different parameters of time by increasing the contraction time or velocity depending on whether we want to reduce or increase stiffness and so on. Control the time and velocity parameters that will induce different effects on the different structures.

Sometimes with the authors there is a mismatch between performance and injury. With a more stiff structure that is good for performance but may not be as good from the injury perspective.

Author opinion:

At APA we always promote the use of using a range of methods to develop athleticism. As Vern Gambetta once said, ‘Assess, Don’t Guess.” The answer to the question concerning what the athlete needs is almost always, ”it depends.”

Do not apply anything as a recipe or established protocol. Look what your athlete needs, because if not, as many people do, we can treat people by email or twitter without seeing the patient!”

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Research– injury prevention programmes need to be directed to correctly and repeatedly perform the movement related to the injury mechanism

- Risk factors- multifactorial including anterior pelvic tilt, hip and trunk flexion and tendon stiffness

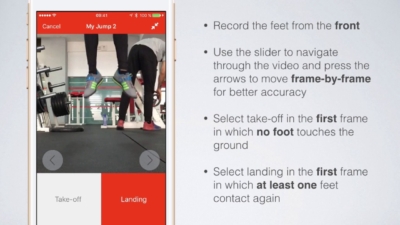

- Assessment- currently we assume that what me measure statically will happen dynamically

- Activation- patterns and sequence are very, very individual

- Velocity vs Contraction type- more important than the type of contraction is the velocity

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

Research Gate:

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 252 Steve Saunders

Episode 248 Hamstring roundtable

Episode 243 Jack Hickey

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Where I am next presenting?

Speed, Agility & Quickness for Sports Workshop

Date: 22nd Feb 2020, 09:00AM-13:00PM Location: Gosling Sports Park, Welwyn Garden City, AL8 6XE

Book your spot HERE

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM