This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 227 – JB Morin

JB Morin

Website

Background:

Jean-Benoit Morin, often known as JB Morin, is a full professor at the University of Nice in France. He has a PhD around sprinting and sprint mechanics.

Discussion topics:

JB on the contrast between academic research and real life

”It’s very, very important to me to go and see people at the elite level, to see the real life issues, and the real life context. In my opinion, it’s a way to ask better questions, it’s a way to challenge what we do, and it’s a way, I think, to better design what we do.

The main issue is that when people work with athletes, they work with individuals, and they work with individual changes in everything. When they read research they see group results, and we all know that group results can be influenced by individual variability. For example, you can see some group results that totally contradict some of your single player’s behaviours. Sometimes applying the group result to a single player might not be effective.”

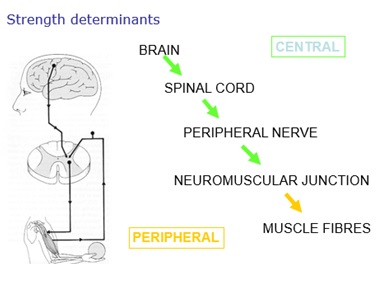

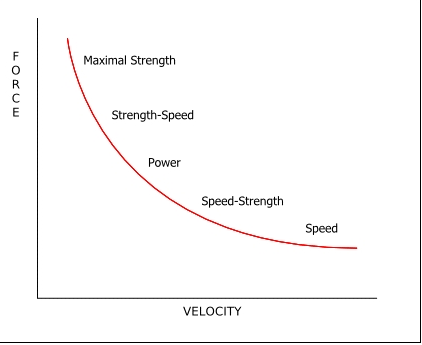

JB with an overview of what Force-Velocity Profiling is:

- High Force- Low velocity

- Mod high Force- mod low velocity

- Mod high velocity- mod low force

- High Velocity- Low Force

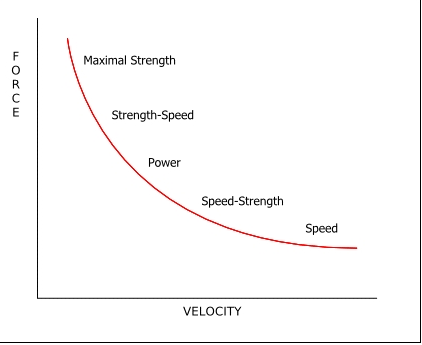

”What we call profiling means building and assessing the individual spectrum of the force output at various possible velocities of motion. We know that every load, every velocity is associated with a different level of force output.

What we understand from the F-V spectrum analysis is that if you analyse performance through a single load velocity condition, like you do a jump test or a 30-metre sprint, you only have one point of information.”

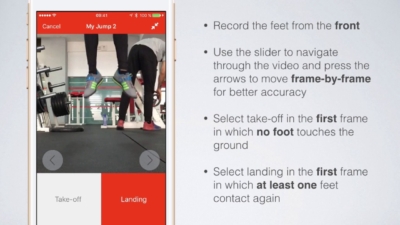

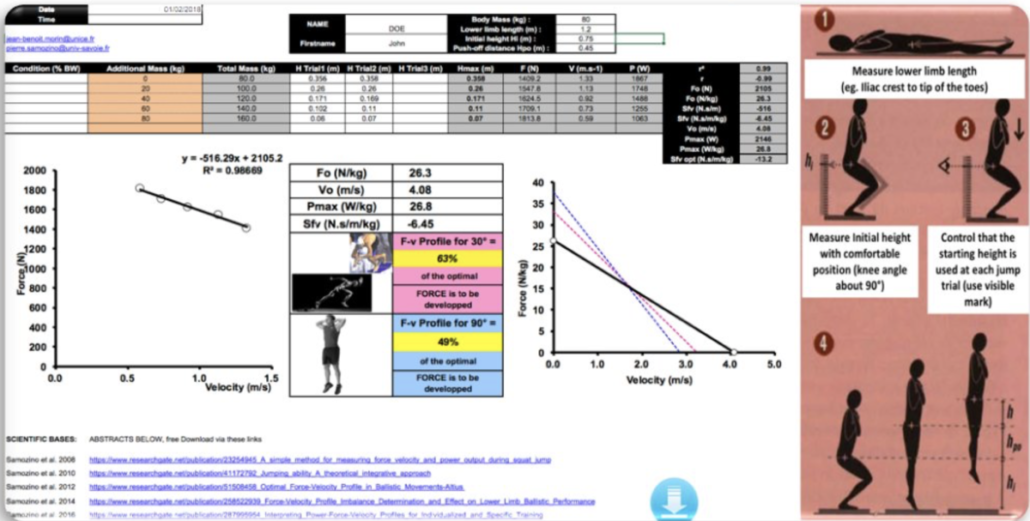

JB on some of the tools and simplified methods to monitor accurately in field conditions

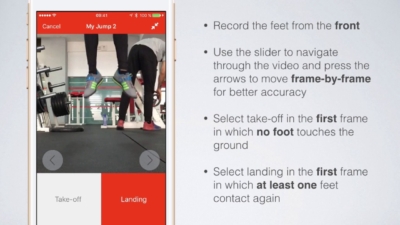

- My Jump app

- My Sprint app

”With my friend Pierre Samozino we published some equations that allowed us to profile people out of the laboratory, and we confirmed these equations against reference devices. Then some Spanish colleagues designed some Apple apps to measure the input easily in the field. One of these is My Jump, the other app is My Sprint. I have absolutely no conflict of interest. I make zero money on what they sell.

These apps only measure accurately the inputs that are needed for our equations to calculate the mechanical outputs.”

JB on how to develop an optimal profile for horizontal or vertical force velocity

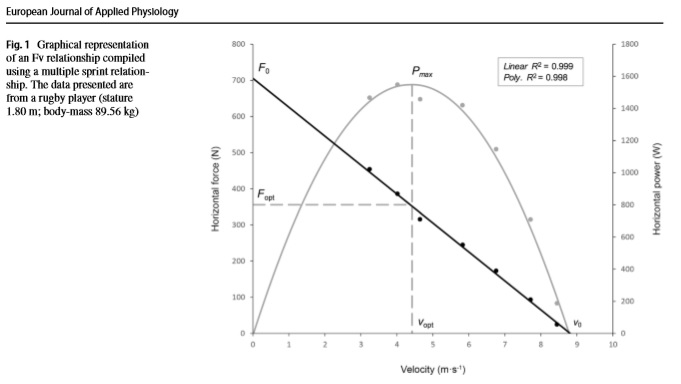

”We have computed the optimal profile. The idea is very simple. You can have the same 30-metre time with very different force-velocity spectrums. And our question was does the force-velocity spectrum influence your performance, because we know that for the same Pmax we can have different profiles.

I can say now that yes, there is an optimal profile for sprint performance. It depends on the distance you want to optimise, so it will not be the same for a 20-metre than for a 60-metre. And so depending on your actual profile and the optimal profile we calculate, we have a better way to individualise the training.

The funny thing is that we have taken the 40-metre distance, and the actual profile of Usain Bolt, and we concluded that for his world record his F-V profile for that distance was not optimal. It means that by having a different profile than he had, he could have run the first 40-metres faster.”

JB on what the Force-velocity profile actually looks like

”The analysis of the profile is velocity based force output. Basically in sprinting and jumping, the profile looks linear. It’s clearly linear even if the muscle cells or the muscle fibres have a hyperbolic F-V profile. But when you do a global multi-joint exercises it’s linear, and so it goes from your maximum theoretical force output, down to your maximum theoretical velocity output.

Then, our approach is to say where is your weakness on that curve? For example, if you’re someone who does only five 10-metre sprints, like a basketball player, maybe if you have a weakness on the V0 end, it’s not going to be a big issue because your sport doesn’t require a high V0. If you are the same guy with the very same profile but you’re a 100 metre sprinter then yes, you will need to work on that.”

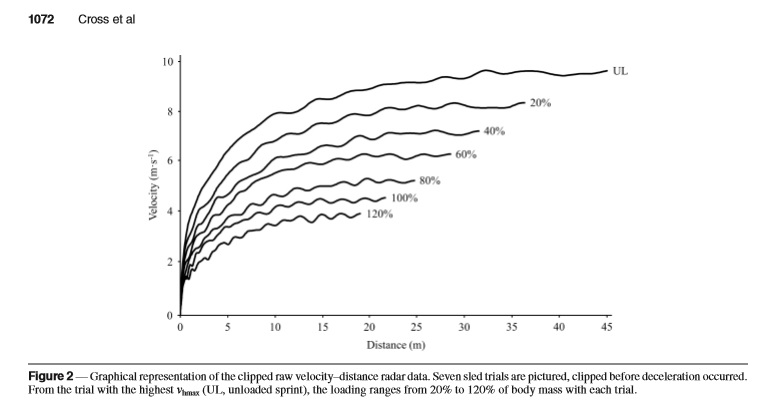

JB on Resisted sprints and where we are at in terms of the research

”If you use zero resistance, you will sprint for a couple of seconds close to your V0 and then the higher the resistance the closer you will sprint to your F0. Resistance is a way to set the running velocity, because there’s a clear relationship.

Research wise until 2017, there had been some research on resisted sprints, but only 10% body mass let’s say. I will not talk body mass, I will talk decreasing speed. So 10% decreasing speed, or 20% decrease or maximum 30% decrease, and there was no research on other parts of the spectrum. So it means the complete left side of that spectrum, even the middle side had not been investigated. And even to date, there’s only one single study using loads that decrease your velocity by more than 70-80% which we call ‘heavy sleds’ or heavy loads.

The problem with using percentage of body mass is that it can lead to very different resisted forces according to the surface, for example dry versus wet turf or concrete versus grass. So it’s better to calculate as a percentage of velocity decrease. But to do that, we need to measure velocity. The best way is to set the load as a function of the decrement in velocity we want to observe.”

JB on how resisted sprints can effect athletes mechanically in terms of what their actual sprinting will look like

”We need to be very careful between acute changes, which means how they run while pulling that resistance, and obviously some things change. Yes of course the running pattern will change when you pull a heavy load. But the big question is not acute changes. It’s chronic changes. And to date there has been no study on heavy loads and how the sprint pattern changes. How do the acute changes interact with sprint performance? What do we want? We want people to run fast, okay? We have to put that as a balance between changes in sprint kinematics and changes in sprint performance”

Author opinion:

I’ll break scientific convention here for once and speak in first person!

I have personally listened to JB Morin speak in the UK on three separate occasions and I have used the Force-Velocity profile with one of my athletes. Even after listening to the presentations, this podcast and reading the journal articles I’m still not 100% clear but one of the key concepts I have needed to get my head around is what JB means by ‘optimal.’

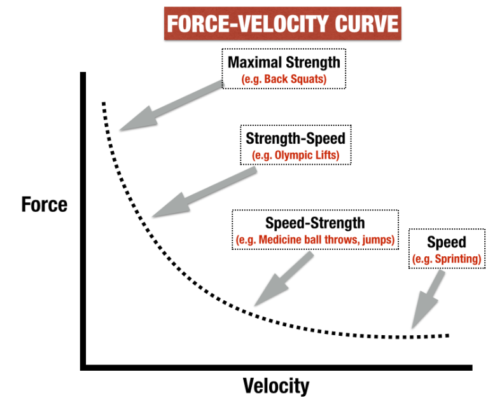

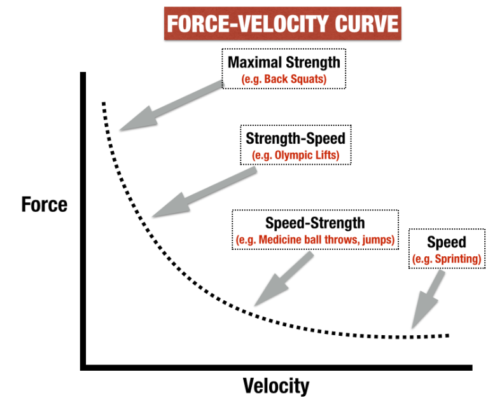

Where I think we have got things confused (or at least I have), is in terms of where certain types of activities fit on a Force-Velocity curve, Below is an example of one of the more accurate interpretations in my opinion. I say this because it puts jumps closer to the middle of the curve. If you’re not convinced just look at the velocities of sprinting versus jumps. Jumping take off velocity is much slower than sprinting velocity.

My understanding is that we can assume that for most athletes doing a squat jump or countermovement jump, the ‘optimal’ jump performance should occur at their own body mass. If it doesn’t it’s because they don’t have the optimum balance between force and velocity qualities. In my head I am visualizing a body mass squat jump as being roughly in the middle of the F-V spectrum and so intuitively it requires a balance of force and velocity to perform it well (otherwise it wouldn’t be in the middle)!

Furthermore, the relative difference between actual and optimal represents the magnitude and the direction of the unfavorable balance between force and velocity qualities. The goal of training therefore is to identify the imbalance (Force Deficit or Velocity Deficit or Well-Balanced) and then carry out an individualised training programme that will target different parts of the F-V curve.

A word of caution: A Case Study

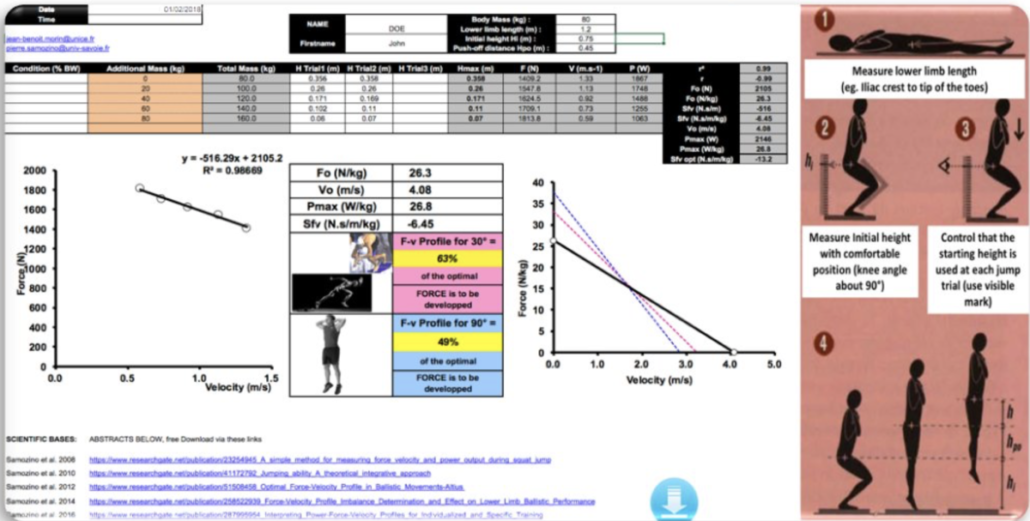

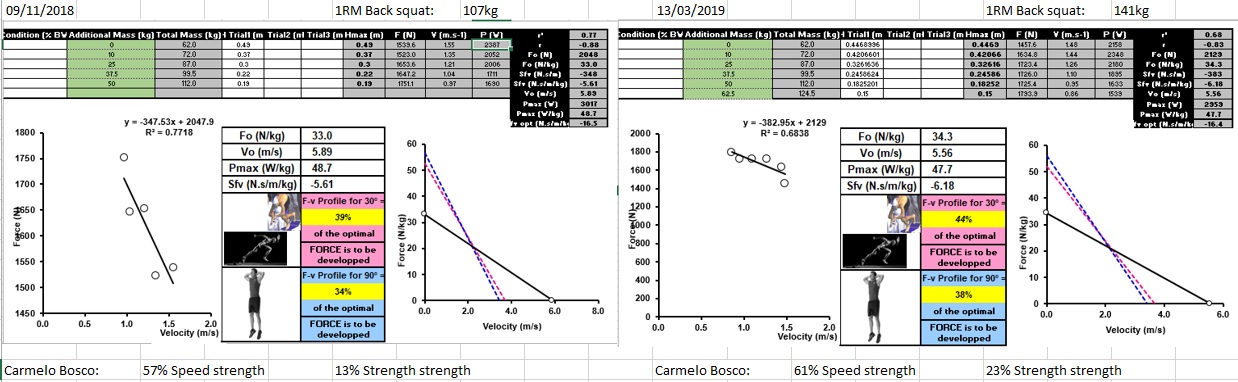

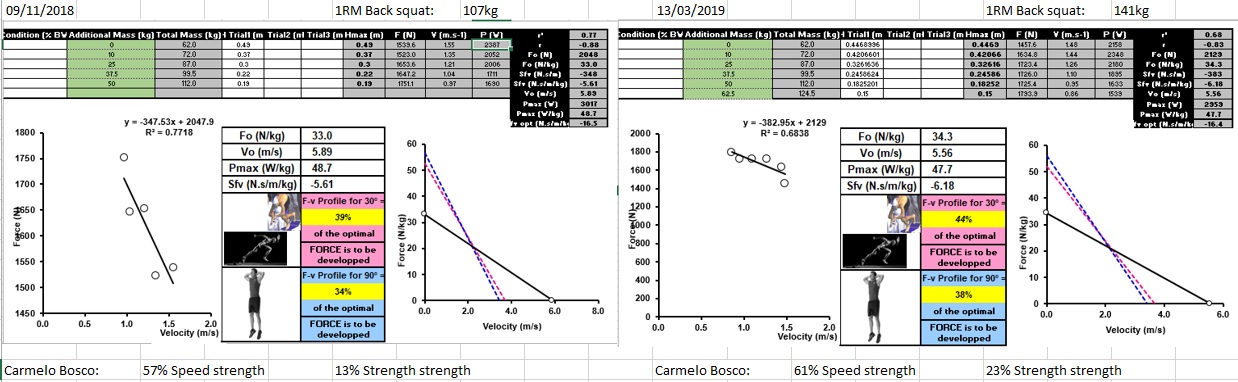

I wanted to give you a bit of real world feedback on my experiences of using the spreadsheet that JB has made available on his website. A bit of background, I asked my athlete who is a 60kg female elite athlete to do this test early in her winter training and again towards the end of it. During the same week she did a 1-RM prediction of back squat using a Gym aware with submaximal loads up to 85% 1RM.

I also used a Carmelo Bosco formula (which was inspired by my reading of Jeremy Sheppard’s work) to determine what percentage of her body mass squat jump height she could reach with 50% (speed-strength) and 100% (strength-speed) of her body mass loaded on her back.

Initial findings:

Initial feedback from the squat, the Carmelo Bosco formula and the F-V profile (34% of the optimal) was that she was Force Deficit. So I spent the winter period making sure there was a strong emphasis on maximal strength.

When I did my analysis of the training block I was delighted that she had gone from 107kg to 141kg back squat, her speed-strength percentage had shifted from 57% to 61% (65% was the target) and the strength-speed percentage had shifted from 13 to 23% (35% is the target). We still have a way to go but a 10% improvement of strength-speed was great in my book.

When I did the F-V profile re-test it only went from 34% optimal to 38%. I was perplexed!!!!

Thankfully JB was kind enough to take a look at my spreadsheet and the first thing he said was- ”Daz- you cannot use this data unless the R2 value is at least 0.95.” All the validation studies required this level of correlation. JB said that in the piloting period he found that in less well trained athletes such as some of the youth volleyball players he worked with they also had lower R2 values and a lot of this was to do with poor technique.

Looking back, my athlete was not doing lots of heavy squat jumps in the training so her main exposure to the task was during the actual testing. JB said he was confident that without looking at the video he would imagine that she did not perform the exercise well with loads. So it didn’t allow you to see the improvement in her F0 that was probably there.

He also highlighted that she didn’t have a nice enough spread of loads. In one instance where she attempted four loads, the final load was too close to the penultimate load so this creates a bit of noise. In the case of the re-test, she did attempt 100% body mass but because her technique wasn’t great, the extra spread in data was most probably offset by poor mechanics!

So the lesson is check your R2 values and to ensure they are very high, make sure the athlete is very competent in the task, and the loading is spread evenly across a range of loads.

Top 5 Take Away Points:

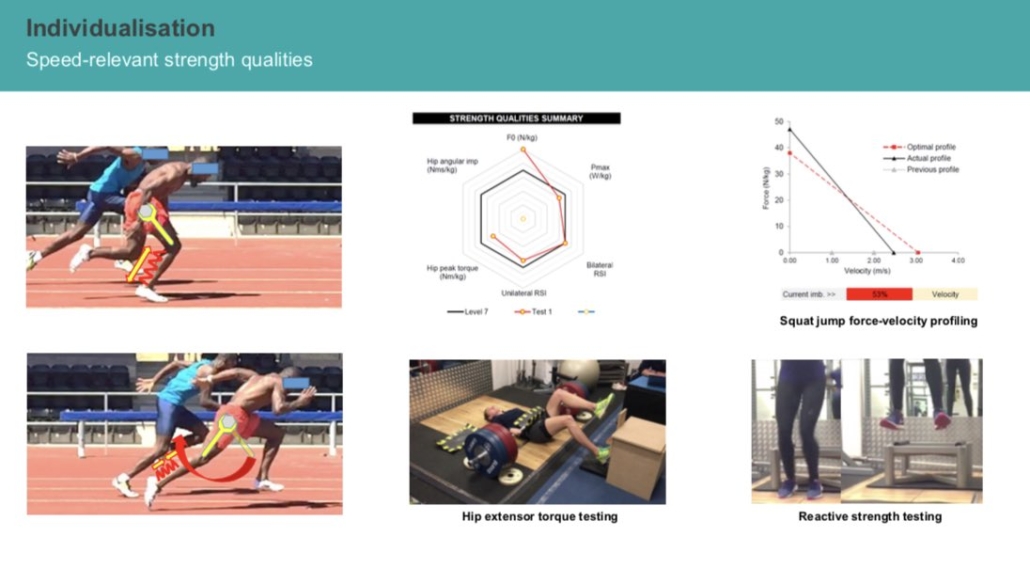

- Individualisation– new approaches to academic data analysis should consider the group response and also the individual response

- Build a profile of the athlete– don’t just look at split times and jump height, look at how they sprint and jump and use a F-V profile to see the imbalances!

- Resisted sprints– set the load as a function of the decrement in velocity you want to observe

- Valid data is key– the correlation R2 value needs to be 0.95 for meaningful interpretation of the F-V profile

- Decide what’s important– Do you want technically perfect athletes with a consistent sprint technique or faster athletes? Any acute disturbances in mechanics from resisted loads must be balanced with long term improvement in sprint times!

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about? Be sure to visit:

Email: [email protected]

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 367 Gareth Sandford

Episode 362 Matt Van Dyke

Episode 361 John Wagle

Episode 359 Damien Harper

Episode 348 Keith Barr

Episode 331 Danny Lum

Episode 298 PJ Vazel

Episode 297 Cam Jose

Episode 295 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 292 Loren Landow

Episode 286 Stu McMillan

Episode 272 Hakan Anderrson

Episode 227, 55 JB Morin

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 212 Boo Schexnayder

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 204, 64 James Wild

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 183 Derek Hansen

Episode 175 Jason Hettler

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM

=> Follow us on Facebook

=> Follow us on Instagram

=> Follow us on Twitter