ABCs for Kids- a session plan for FREE

Yesterday I had the pleasure of doing some coach education for a group of students in Year 10 and 11 from the Dacorum School Sports Network who undertake work experience, training and development within the schools in the Dacorum network around the borough of Dacorum.

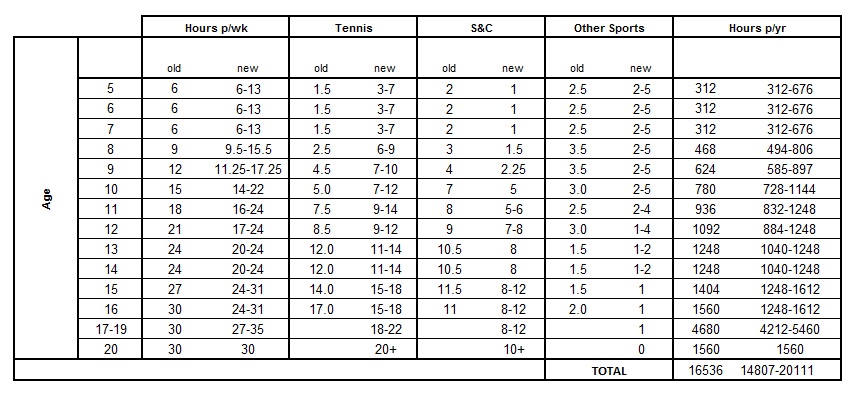

The concept for the two hour workshop was to introduce the topic of Physical Literacy to the coaches and get them to think about how they can work on the athleticism of the children they are coaching even within a sports coaching session. The children in question would be typically 10-14 years although they might also be Primary school aged children 5-11 years.

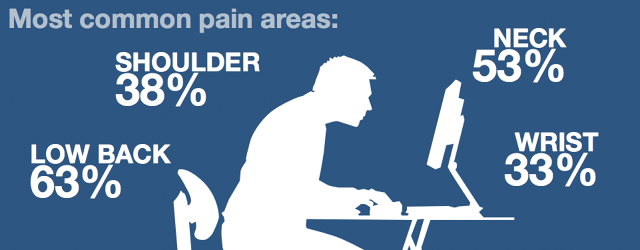

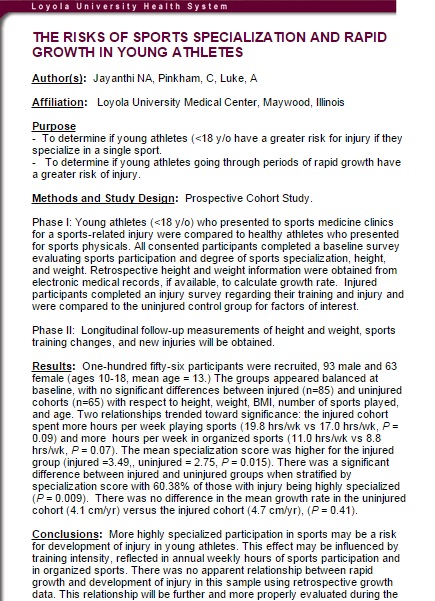

I actually wish more new coaches would get exposure to this kind of topic as it amazes me even now how many highly experiences sports coaches fail to make the link between athleticism and ability in sports. Often it’s not until one of their star athletes gets injured due to a lack of physical preparedness that they are ready to listen.

Don’t believe me- watch this clip. Spoiler alert: be prepared to look away if you’re squeamish.

Below is a summary of what we covered:

Oaklands College, 16th July 2015 1:30PM- 3:30PM

About the workshop:

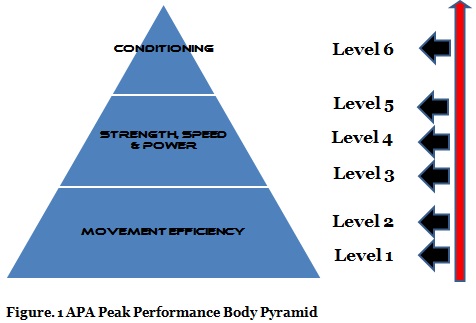

This workshop brought together the presenter’s extensive experience and background in the field of youth coaching to give the participant a thorough overview of the current theory and practical application of basic drills that can assist in the development of balance, coordination and strength for Sport.

The content included but was not limited to the following areas:

- The four components of a warm-up

- The two types of balance and how to train them

- The four types of coordination and how to train them

- The two types of strength and how to train them

About the presenter:

Daz Drake is currently Head of Strength and Conditioning at Gosling Tennis Academy and is Director of Athletic Performance Academy who consult with numerous sports organisations in the south of England. Daz currently looks after the S&C programmes of some of the top ranked male and female professional Tennis players in the country.

Warm-up:

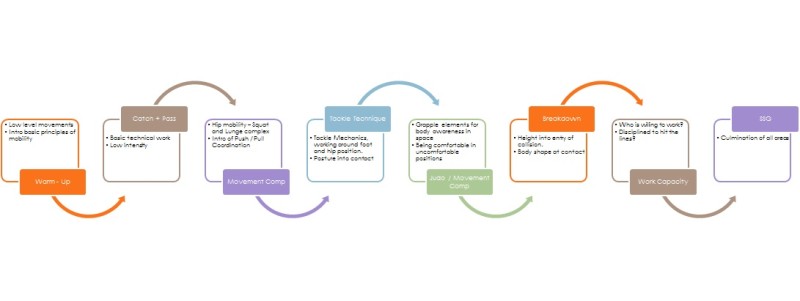

Ask any sports coach how they integrate strength & conditioning into their sessions and if they integrate it at all it is usually always in the warm-up. That’s why it is essential to maximise this time- which depending on the programme can be anywhere from 5 to 15 minutes typically.

‘RAMP’

Pulse raiser: skipping / Swedish handball / Simon says / Follow the leader

Activation: single leg balance / crawling

Mobilise: big steps / mini man / caterpillar walk

Potentiate: Coordination the big 7- single knee dead-leg lift / side steps / high skips / cross-over side shuffle side shuffle / butt kicks / cross-overs / high side skips

You can actually view an example of the Junior Academy complete warm-up below.

Please note the Junior Academy warm-up is for our 12 years and above age-group. For the 11 and unders we would use a couple of different balance and crawling challenges but it’s essentially the same concept.

Main Session:

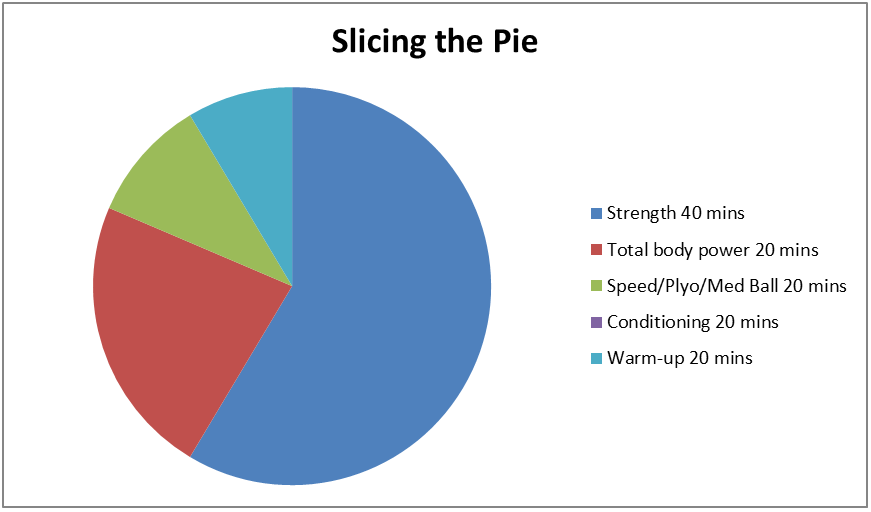

We went on to build on the warm-up and actually look at what we might do with a group of young athletes. If I have 60 minutes with a group my session structure might look something like this. I have spoken on numerous occasions about the benefits of a ‘complex’ session structure for developing athletes. By this I mean a session which hits a lot of different components in the same session. I find this gives you the most ‘bang for your buck’ when you’re aiming to develop multiple athletic skills with children who will improve in pretty much everything you give them in the early years.

| SKILL | (balance)>>(coordination) | |||||||

| SPEED | (Jumps)>(reactions)>(1st step: Fast feet/start)>(Sprints) | |||||||

| AGILITY | (multi-directional speed) | |||||||

| STRENGTH | (Animals/Gymnastics/Partner work) | |||||||

| STAMINA | GAME | |||||||

Some ideas for drills for Balance, Coordination & Strength:

We finished up by looking at some different drills we could use for a few of the components. Watch out over the next few weeks for videos that I will add to this blog post of some of the drills below.

Balance:

Drills:

Static balance: shoulder stands / hand stands / single leg balance / compass reach

Dynamic balance:

- Walks- marching / lunging (add bead bag)

- Reaching- squat & reach / lunge & reach

- Jumping- 2-to-2 / 1-to-2 / 1-to-2 / 1-to-1

Coordination:

Drills:

Rhythm: skipping rope / partner mirroring / ladders / hurdles

Synchronisation: crawl / sidestep / hop, skip, jump / rolling / get ups / throw

Orientation: ball around body / ball above head / catching / striking / rolling- advanced

Differentiation: throw to targets / bouncing / football keep ups / racket keep ups

Strength:

Core Stability:

Core foundation: plank lifts / bird dog / dead bug

Core endurance: back raise hold / glute bridge hold / plank hold / 45 degree leg lower hold / dish hold / crunch hold / side plank hold / side crunch hold

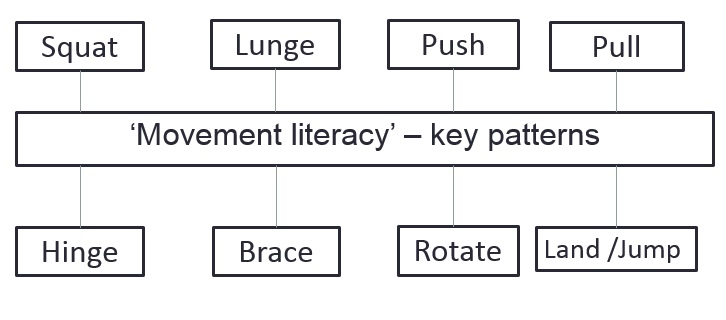

Foundation strength:

Squat: Partner squats / Wall squats / Wall squat and reach / Get ups

Lunge: Split squat / rotational squat / lateral squat >> progress to lunge

Push: Push up hold / elevated push ups / push up

Pull: Partner rows / Inverted rows / Jump pull ups / Pull ups