Pacey Performance Podcast REVIEW – Episode 410 Shawn Myszka

This blog is a review of the Pacey Performance Podcast Episode 410 – Shawn Myszka

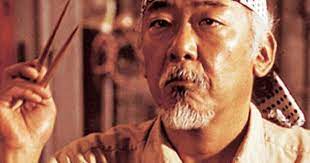

Shawn Myszka

Shawn is a Movement Skill Acquisition Coach at Emergence and currently serves as a personal performance advisor and movement coach for more than a dozen NFL players and has partnered with 108 NFL players and counting over 15 seasons.

In this episode, Shawn details his approach which dives into the world of ecological dynamics and a constraints led approach. He explains how his approach differs to a “traditional” approach of pre-planned movements and drilling them time after time. Shawn presents an example of a closed drill which aims to improve cutting and develops it into a much more open drill so the athlete has to react to a changing environment, much like they would have to do on game day.

🔊 Listen to the full episode here

Discussion topics:

”For those of us who don’t know much about your coaching philosophy can you share a brief background on yourself?”

Coaching agility is much more than setting up cones and letting the athletes run routes around them. Agility is much more than just change of direction ability. But with so much complexity to improve the physical quality of “agility”, how can we coach it effectively to ensure transfer to the field?

I view movement and movement skill as my main objective. I believe that sport is a problem solving activity where movements are just used to produce the necessary solutions

We can impact and influence how athletes are interacting with their environments in a much different way if we view movement and movement skill in this fashion. Things like ”abundance of strategies,” things like ”adaptability” and ”dexterity” these are things that have shaped my form of life, the way that I view movement and sport behaviour and performance.

I am very American Football orientated but I have co-founded and operate as the co Director of education of an movement skill & education company called Emergence.

”Are you employed directly by players or do you also do consultancy with teams as well?”

”I do some consultations with teams, usually it’s on a very short term situation where I will present to staff, I will come in an for one, two or three days and maybe analyse their practice activities and get into how it is I feel that they can make them more ALIVE, so that’s a term you’re probably going to hear me drop a few times – this idea of alive problems being solved within environments. Mostly I work directly with the players and become a personal performance advisor/movement skill acquisition coach for players that they and I lock arms with one another to attempt to polish and sharpen their craft – specifically how they behave on a field. It was the NFL players that referred to me as the ”Movement Miyagi.”

Obviously I still attack things like general physical qualities and general physical preparedness so I’m still doing weight room stuff. I actually used to be a strength & conditioning coach but I morphed into this role because I felt there was a major gap between what we were doing in the weight room and what they were doing on the field. I elected to exist within that gap and attack the gaps within their skill set, particularly from movement standpoint.”

”Why did you decide to go down that route to be known as a movement skill acquisition coach and really niche down in that area?”

Learning Environments that weren’t really learning environments

”I was finding that that gap was getting bigger and bigger – and the position coaches within the NFL are very intelligent when it comes to the X’s and O’s, tactics and strategy, principles of play, but really I have been on my soap box during this pre-season about some of the horse shit that is being done on individual drills, where position coaches are taking 10-20 minutes to work with individual players each and every day and they are decontextualised isolated drills- where there is rote repetition which is being prioritised. It starts to show us the limitations in how they view movement behaviour. But what I was finding was that gap was getting bigger and bigger because strength & conditioning professionals were really prioritising the same thing within their learning environments, that they weren’t really learning environments.

When they were addressing speed or change of direction qualities it was in highly irrelevant fashions to the way that it would be expressed on the football field. So I felt that that gap was getting bigger and the player was getting lost in the middle of this saying how do I put those physical qualities to use in highly practically relevant ways to functionally solve problems in my world?

That’s what the players care about – they are there to become better FOOTBALL PLAYERS. So everything that we do at either end should support and supplement their craft in that way – how they were having to solve problems, the abundance of movement strategies, the diversity withing strategy, their decision making, their perceptions, their actions all being coupled and intertwined in a way, that allows them to really connect to their environment and become more functional problem solvers and more dexterous movers.

People hear Movement Miyagi or movement skill acquisition coach and they think that what I’m doing is chasing perfect execution of motor patterns- motor system degrees of freedom. That’s what they view coordination of movement to be. I do not. I view it as movement skill in relation to one’s environment which is constantly changing, that has emerging and decaying opportunities and I want to assist the player in perceiving and selecting and acting upon those opportunities in their own unique and authentic fashion.

The position coaches really weren’t doing that, and the strength & conditioning coaches weren’t doing that because they don’t view movement skill in this fashion and so things like speed and acceleration and power and explosiveness wasn’t really being expressed on the field. That’s why I have been knocking on the door of the NFL to change and adjust its talent identification procedures particularly with the NFL combine, since 2013-14 I’ve been saying the stuff you are looking at isn’t actually overly relevant when it comes to how they are going to behave on a football field on NFL Sunday.

”Bear with me because I have a theory. The ‘S’ side of the S&C coach is 90% of education when it comes to an under- or post-graduate education. So we are heavily educated in that area and that translates into a working environment? We like things in a box, to be measured. We are comfortable in that area. We are not comfortable when things get complex, or a little bit messy. There are a few coaches who like the messy and live in the messy and thrive in that area, but the majority [me included] like the package, like things to be in a row, like the drill where everyone looks the same. Would you agree with this theory?”

We intuitively know that sport is much more about adaptability, that this world will be messy, that no two problems are ever going to be the same in sport. There will be sports that seem to be more repeatable that have less complexity and less interacting component parts. Yet when we really look at it, we see that there is a lot more messiness than we are willing to acknowledge, that one’s adaptability is still likely to be the calling card, the higher the levels of skill and mastery we go.

So something like running a 100m sprint on a track may at first seem like a very repeatable skill but we can still analyse the performer-environment relationship and attempt to facilitate a more functional athlete-environment relationship through and because of these changing constraints – the weather, the track, the shoes and rather than chasing this perfect technical model, perhaps what we want to chase is dexterity (Bernstein, 1960s).

The ability to find or organise a movement solution for any emerging movement problem under any situation and in any condition.

”How do you reconcile the struggle to fill the gap between the orderly approach of rote repetition and the chaos of the sporting action, and the need to reign it back in so I have more control. Would you say that people do struggle with this middle bit like I imagine they do?”

”As I found my way towards an ecological approach I realised that for the first 5-6 years of me working with NFL football players I was the traditionally minded individual that you were speaking to. I was chasing a rote repetition perfect technical model of almost any movement action or technique that the athlete could organise or coordinate.

At the end of the 2012-2013 season I remember asking myself the question really poignantly, ”Are the players performing on field because of the work we do, or in spite of the work we do? And I didn’t like the answer to that question. I very rarely saw them behaving with this perfect technical model that we had beaten the path towards with that traditional approach. If the athlete couldn’t behave in that way, I just felt they needed more repetition, or more feedback, or more instruction or more consistency. I realised I was neglecting decision making, I was neglecting perceptual information and I was really separating and segregating those processes of the human movement system.

Dexterity doesn’t live in the movements or actions themselves, but it lives in its interaction with the environment

So if it’s about interaction with the environment then that environment has to present some ALIVENESS.

When you chase that perfection you’re actually doing the athlete more harm than good when you do that. I was treating them with kid gloves, and somewhere along the way they became less prepared to adapt to the environment when the environment was going to ask that of them 50, 60 or 70 times a game in an NFL game on Sunday.

I can still manipulate constraints and scale the information so it’s a little less. So it isn’t this complete free for all. Self-organisation that goes a long with an ecological dynamics rational is not like a free for all, we don’t just let it go. It’s not like I don’t ever explicitly suggest or attempt to facilitate changes to behaviour for the athlete – but I let them try to figure some shit out on their own at times too!

Shift our hat from being a dictator to a little bit more of a facilitator by setting an environment where we don’t have all the answers and by attempting to manipulate the constraints so it does MEET THE ATHLETE AT THEIR CHALLENGE POINT, which is an art in and of itself.

”How would we as coaches make our way more towards the end of the coaching spectrum that you are talking about?”

”How can we immediately interject more ALIVENESS into the problem? If we are viewing sport movement behaviour as a problem solving activity, then how can we actually turn this into a problem that has has dimensional levels to it?

How can require more from the behavioural organisation of the movement system with PERCEPTION, COGNITION, INTENTIONS OR DECISIONS?

We would remove those cones and put bodies there to promote aliveness. Rather than being inundated with information from coaches, let them reconnect with their own information about how their environment might be changing (which the environment in and of itself won’t be and with a cone the environment won’t be changing).

It doesn’t have to be an overly chaotic or complex environment, it could be just one where at least there are some moving bodies in it, that the athlete has to become sensitive to and attuned to because those moving bodies and the space they occupy, angles, speed and posture will all dictate the behaviour of the athlete who is going through the ”drill.”

We don’t need a tonne of messiness but we likely need either an opponent or a team mate in the space. How do we make it look and feel more like sport? (Notice I didn’t say identical to sport). An 11 vs 11 is the most representative but we don’t often exist there because they can’t always handle the amount of information from that complexity, so we might have to scale it down to 1 vs 1 or 1 vs 2, 2 vs 2, 3 vs 3 or more small sided game activities that we can all do if we use some more aliveness.

”Is there any place for closed drills, for example, you’ll hear coaches saying, we are just getting them warmed up before we drill down and then chuck them in. Is there any place for closed drills?”

”If you adopt an ecological dynamics framework where our relevant scope and scale of analysis is on the performer-environment relationship, and that athlete, particularly in a team based sport such as American football, isn’t going to have to coordinate, control and organise their movement behaviour NOT related to an OPPONENT or an alive environment, then I do not believe there is very much need at all.

In order to act upon what we perceive we must have the action capabilities in order to act! All that is saying, is that I have to have access to that strategy within my movement toolbox. For example, if this situation requires me to execute a cross-over cut but I have tremendous knee tendinitis and I can’t cross-over on that leg I might have to scale down the information down to such a level that the athlete can explore and instead have a live opponent who is stationary. This will reduce the complexity and aliveness- the opponent isn’t moving. But at least if it’s a human and not a cone, they can still reach out and touch you, they are much bigger and even just putting a human there changes the behavioural organisation and what an athlete has to perceive. There are likely not looking down at the ground any more for that cone and instead looking at the posture and position of the opponent.

There might be a place for more closed drills (on a spectrum of fully closed to full open) but not in the traditional sense where we are telling them exactly how to move, exactly where to move, when to move etc.

That I think is the danger. Or, the situation where we are chasing the same model for everyone; talk about thinking as though we have all the answers! Movement behaviour in sport is a lot more complex than that! If you took the top 10 running backs in the NFL and presented them with similar behaving movement problems to solve, guess what? No two movement solutions are going to be the same. They could both functionally solve the movement problem- they would all make the defensive player miss (the tackle) but in their own authentic and unique way.

”The other end of the spectrum to what you are talking about is linear progression, it involves doing X drill, okay that’s successful, now we move onto this, making it more complex or whatever progression it might be. On the side you’re talking about the linear progression is not so obvious. How would you advise people to try and make sense of that to allow them to feel more confident in that world?”

”First we have to acknowledge, at least from an ecological dynamics rational, and we when look at complex dynamical systems, is behaviour and the interactions that lead to that behaviour is NON LINEAR. So small changes to the way that something that unfolds from a context standpoint, could lead to huge changes in the way in which the behaviour emerges.

We never stand in the same river twice.

Second point is we are constantly presenting the athlete different situations or contexts to test the stability or flexibility of the movement solution. If we start to see movement behaviour that is ‘stickier’ that maybe is emerging on a more frequent basis, well I want to test that ability to match or emerge in different problems. So I’m going to change positions and speeds of opponents and use different size spaces to work in. And all while I do that we are basically perturbing the system to see what else may emerge.

Top 5 Take Away Points:

- Decontextualised isolated drills- where there is rote repetition – is being prioritised but it’s time to adopt an ecological dynamics model

- One’s adaptability is still likely to be the calling card, the higher the levels of skill and mastery we go.

- ALIVENESS – We want alive learning activities not drills

- We never stand in the same river twice – so respect the non-linearity of movement.

- We can still create progression within an ecological dynamics approach

Want more info on the stuff we have spoken about?

You may also like from PPP:

Episode 400 Des, Dave and Bish

Episode 381 Alastair McBurnie & Tom Dos’Santos

Episode 380 Alastair McBurnie & Tom Dos’Santos

Episode 372 Jeremy Sheppard & Dana Agar Newman

Episode 217, 51 Derek Evely

Episode 207, 3 Mike Young

Episode 192 Sprint Masterclass

Episode 87 Dan Pfaff

Episode 55 Jonas Dodoo

Episode 15 Carl Valle

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM