Setting Standards for Athletes in Coaching Sessions

This blog is a bit of a change up in the usual sport science topics that I talk about. Like many blogs before it, my inspiration has come from actual conversations with my coaches. I have been talking with some of my team about the psychology of coaching and about the two qualities that I think world class coaches have – and they are CONNECTION and STANDARDS.

A world class coach will be high on the level of connection they make with their athletes and also high on the level of standards they expect from themselves as the coach, and also the standards they expect of their athletes.

In today’s blog I’d like to focus more so on setting standards, but in reality they will be intertwined because I believe that setting high standards and holding athletes accountable is one of the key ways to establish trust and respect (build connection) and show them how much you care about their development.

Setting Goals

Before we get into the main discussion I wanted to set the scene for why this psychological work is so important. Prior to working with players at a deeper level I had generally ticked the ‘psychology box’ by setting goals with my athletes.

Most of the athletes I get to work with are generally labeled as ‘talented’ and are also known as ‘performance level’ rather than ‘developmental level.’ If you’re not familiar with this term it is a way to describe a group of athletes who are playing competitive sport- and train to win. They are usually more committed and play the sport several times a week. Developmental groups are a collective of athletes who usually play the sport less often and play for fun. Of course there will be an overlap but that is generally how it works.

This means often the goal they set related to some kind of ranking goal, or another outcome goal such as winning a particular tournament.

I used to get very frustrated because I was working with ‘talented’ athletes who set goals that I considered to be pretty high, and yet they would not put the work in that I thought was required of them.

There are two things to consider here. First of all, is the goal they set truly motivating to them and excites them (makes them feel something emotionally) or is it just a paper exercise that they have only committed to at a cerebral level.

The second thing to consider here is that they may be motivated by the outcome (to achieve a certain ranking goal etc) but perhaps they are not motivated by the process of what they need to do to achieve it. In this case they desire something but they are not committed. This is especially true in strength & conditioning. Sure there are athletes who love to be in the gym (and probably take confidence from it) whether that be because they like to feel strong, they want to improve how they look or maybe they have an injury history and they feel this helps them keep the pain away. But there are many that go into the gym because they have to – because it’s part of their weekly schedule, and they know they need to do it as a means to an end.

I hear it all the time, ‘my athlete doesn’t want it. He doesn’t want to put the work in. It’s not my job to motivate them. They should want to do it. ‘’

Until I got into coaching at a deeper level I would have tended to agree. I would have said they need to be motivated. I would have said that I only want to work with athletes who are motivated to do the work.

But let’s revisit what I said earlier. They desire something, but they are not committed……yet. We don’t know what we don’t know. I now see my job as a coach that has a trainer part and a teacher part. We need to teach our athletes why and how what we do in the gym helps them achieve their goal. Only by repeatedly making the connection between the gym and the sports field can you speak to their main motivation – their sport. We need to understand the principle of ‘Pace and Lead.’ We start at their pace and slowly lead them to higher levels of commitment that are more aligned with their goal. Of course if over a period of time they don’t align then we need to address whether the goal is appropriate.

One final point is that if they do have a goal that motivates them and they are very passionate about it – you also need to be careful to make sure this doesn’t anchor negative expectations that makes them fear the future and worry about not achieving it.

Goals are not about creating expectations. They are a way to direct effort towards improvement. Which means there is also the thought that you don’t need to set goals at all, as long as the athlete is continually committing to self-improvement and is making progress. This also applies to the coach. Perhaps you have very high expectations of the athlete, or yourself. This can create a negative environment because you don’t recognize any efforts towards improvement however small.

The same passion that makes the athlete say “I want it so bad” has to be managed so that they can handle the situation if they don’t get it. Expectations are the same things that create frustration in the moment when performing because you think you ‘should’ be performing better. It’s okay to have a certain level of expectation about what you want to do in terms of the processes you want to hold yourself accountable to but you have to be able to accept that processes and outcomes are not always cause and effect. Sometimes even if you do everything in your power you can’t control the result.

”If you do the best you can, you’ll never be criticised by me.” Sven Goran Eriksson

So already you can see that the simple process of setting a goal can actually have a few more levels of complexity. This is why I am convinced that it is so important to better understand the psyche of your athletes. It is so easy to be swimming against the current and feeling resistance if the athlete’s behaviours are not aligned with your expectations and vice versa.

Setting Standards

As a coach I used to have expectations of my athlete’s abilities. Just like my athletes, I got caught up in the expectation of how well they should do (because they are talented).

I now personally try to keep an open mind. I see my role as a coach as ‘Nurturing nature,’ meaning I maximize whatever natural abilities someone has. I’ve been in the elite environment too long to put any energy into speculating whether someone will make it or not. Children that I have been convinced would ‘make it’ as a professional based on their incredible talent fell away and equally children that started off as a small, clumsy, heavy footed slow athlete grew into a tall, strong, powerful athlete who surpassed my expectations.

My expertise is partly built yes, on knowing what world class looks like, so I can cater for the talented athlete who wants to know what areas they need to work on to reach elite level. But for everyone regardless of talent, my role is about having the skills to appraise where they are now and create a challenging environment to take them further, one session at a time.

Not having expectations about where their future performance could reach is not the same as not having standards and objectives for the current session. But the standards relate to things that are within our control and based on personal levels of performance (what I can do) rather than outcome levels of performance (what the best can do). It is perfectly reasonable to have expectations about behaviour, effort and even personal standards of performance. We will discuss setting standards at the end of the blog.

My job as the coach is to help you meet certain standards of performance that we know you are capable of.

Ideally I want the athlete to measure their achievements against their own personal standards and how they achieve those standards. My job as a coach is to give praise for effort towards their goals as well as feedback on how to improve their skills.

Influencing Pace of Change

At Gosling Tennis Academy they talk about ‘win now and win future.’ As a coach you have to look beyond the short term- is what the athlete doing now going to still help them win in the future?

Regardless of whether you are achieving success now or not there are always things to improve. The test is to see how willing someone is to keep making improvements. This is Peak Performance.

Peak performance is about focusing on the processes that enable you to achieve your human potential. For those operating in an elite performance environment (focus on the outcome of winning) then this same focus on the processes will also lead to the greatest chance of winning consistently.

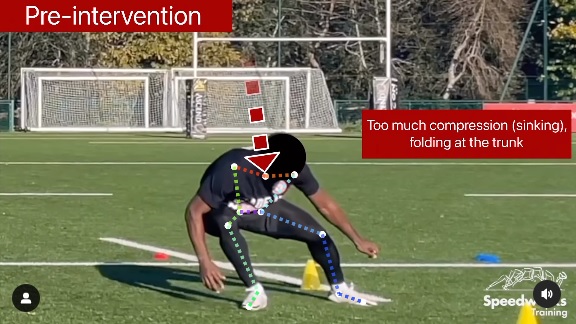

Part of focusing on the process that leads to continual improvement may mean having to think about something for the first time or adopt a new technique etc. Therefore your job as a coach is to help them develop or ‘change’ their behaviours to help them get the specific outcome they want. This may involve changing how they think about, feel about and do something.

Despite an agreement on a shared goal you will experience a number of challenges to this way of thinking. You see, humans by their very nature dislike change, especially if it threatens their chance of success (perceived or otherwise). I think it was a quote from Brett Bartholomew’s book ‘Conscious coaching’ that my colleague Howard Green quoted: ‘Humans are different to other mammals in that more than attention they value recognition.’ For this reason, winning is such a strong driver of behaviour- because it gets a lot of recognition.

Logically speaking then it would make sense that those who are consistently under-performing ought to be the most open to change, and vice versa. But it is not quite as simple as this.

Quite often someone may be willing to make a change and will commit to the change in training but under the pressure of competition default to an old habit. They may want to make the change (desire/thought) but not be able do it in competition (behavior/action). This may be due to having a habit that comes out under competition pressure.

This attachment to what we know and do gets stronger the more that they do that thing. This is compounded when it has been associated with a period of success as it may lead to a belief that this behaviour leads to success. The reality might be that they are winning in spite of their approach.

Often negative emotions are a stronger driver of behavior than positive ones. So the negative emotion of fear (of failure or change) will be more important than the positive emotion of happiness (of future higher levels of success). Therefore braking habits takes a lot of time and energy with no guarantees of success.

So far I have already mentioned the word behaviours, beliefs and values so it makes sense to talk about Neurological level of change.

Neurological level of change

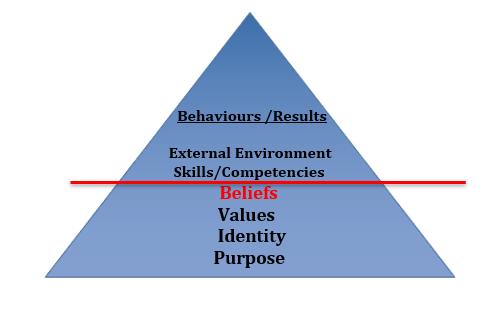

In our day-to-day life we are ‘behaving’ in a certain way. This is the outcome of our thoughts, feelings, cognitive processing and habits. Our behaviours are like the ‘results’ or outcome of the other layers. As a coach we may typically try to influence/change behavior by controlling the environment and/or instructing them on new skills. As you may have experienced, this may cause a temporary change but once they go into competition they default to their old behaviour. This is why understanding the layers of a person’s psyche are so important.

To truly bring about change you need to impact them at a deeper level.

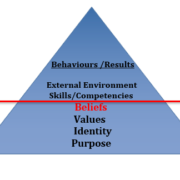

The neurological levels are a concept (developed by Robert Dilts, and based on the work of Bertrand Russell and Gregory Bateson) that explain the level of influence on us (change) as a function of the depth of engagement of our psyche.

Greater change is always possible at deeper levels of our psyche, so for example a change in my identity (I am an international tennis player) would have a greater impact on my behaviour on the court than a change in my skills (how I play my backhand).

Understanding the impact of neurological levels also helps coaches to communicate with players, as you come to understand what is important to them at each level.

I think of this explanation of our psyche like an iceberg. The first three layers (Behaviours/Results, External environment, and Skill/Competencies) relate to externally verifiable and observable actions and are therefore easily seen by others. This is like the tip of the iceberg that floats above the water line. The fourth layer, beliefs, is a bridge to the remaining three layers, which are internal to us, and not easily observed by others. They may not express their beliefs explicitly but if you look just below the surface we are revealing our beliefs all the time in the things we say. ‘’I worked really hard in that match. I deserved to win.’’ This might reveal that the person believes that hard work should lead to success.

You would need to get to know someone really well to appreciate their deeper levels. This is like the part of the iceberg hidden below the water line, and like an iceberg it grows in size just as the level of impact on our actions increases the deeper that we go through the neurological levels.

This is why I said at the beginning that CONNECTIONS and STANDARDS are intertwined. I believe that deeper the level of understanding you have of your athlete’s psyche (connection) the more successful you can be in helping them consistently perform at a high standard – because you know what drives them.

The level of impact on our actions increases the deeper we go through the neurological levels. Changes at the first three levels will require significant repetition for them to become a permanent change and in some cases it may never become permanent, which means the player is dependent on the coach to be reminded.

Peak performance players and coaches will be looking to make changes happen at the deepest level, since this gives the player the best chance of achieving their peak performance. It should enable the player to become self sufficient, since the changes are held at such a deep level of their psyche that they drive the appropriate skill acquisition and behaviours, therefore requiring less reinforcement by the coach.

Hold the smallest detail to the highest standard

Behaviours– we have already spoken about this. These are the physical things we see people do. The outcomes of all the deeper layers. We are always trying to get players to change what they do in order to influence performance. What stops a player doing what they need to? The degree of difficulty a player has in changing behaviour will be directly related to the neurological level at which they are connected to that behaviour. A coach can encourage a player to change their behaviour but if it is not considered important to them then the change won’t stick.

Environment– we live in a society bound by rules and procedures designed to guide our behaviours. Most of the ways society influences our behaviour is through punishment and reward. We are punished for breaking rules and rewarded for following them. However, the ability of external factors to consistently and permanently influence your action is very limited. I will clarify this point further because at first glance it may seem controversial.

I think of the environment we create as being like the flow of water that can influence [fish] behaviour. But as much as we can ”influence” behaviour – if a salmon is set on doing things a certain way it can and will still go against the flow.

Fact – All salmon are born in rivers or streams and all of them return to the same river or stream they were born in to give birth to a new generation of salmon. As they can locate their specific natal spawning grounds, they have to swim upstream to get there.

As humans we fear change and like to conform to the masses. Therefore at a societal level we feel safe living in a world with a degree of predictability which gives us comfort. In this sense the environment does determine our behaviours at a societal level. In some ways elite sport plays into this societal pressure to conform. No one wants to get left behind so when the National governing body rewards talent by giving extra funding to the best players at each age group it causes a change in behaviour. Because money is something we all value, suddenly winning becomes so much more valued as it could lead to funding.

The flip side of reward is punishment. It could also be argued that certain coaching environments are effective in driving behaviour including the armed forces and even some well known sports academies and institutions. It could be argued that this is built on a basis of fear, and that the behaviour is carried out because the person fears the coach or the consequences of under-performing.

The success of the environment is predicated on the coach being there at all times to remind them. How many people do you know who have been caught speeding only to re-offend? Or who behave in a certain way when the coach is there but left to their own devices behave differently?

Neither of these environments are associated with peak performance. Peak performance players become self determined and begin to see how their internal world (in their mind and body) influences their performance in the external world. Any behaviour that is dependent on the coach or external factor to be present to drive behaviour is not peak performance.

As well as rules with consequences, as a sportsman or woman the main external factors relate to the people, places and things around you. This includes training centre, court surface, tennis balls, coach, practice partner, friends, parents etc. These are all external to the player and will have an influence on their performance.

The level of influence of external factors increase significantly as the player develops ‘’beliefs’’ in respect of their environment. A player may say, ‘’I don’t play well with that person, or on grass or when my parents are watching etc’’ so they are giving you information in respect of the external environment (practice partner, court surface, parent) linked to a belief. Do they really not play well on grass or is it that they don’t like losing and they feel their performance is affected by the surface (which is a belief)?

Competencies/Skills– this is where coaches spend the majority of their time changing behaviours at the level of the skills. The higher the level of skills a player has the greater their chance of performing at higher levels. This may be mental, technical or physical skills. We have all come across situations where in competition the player doesn’t use the technique they have been practicing. The reasons these competencies/skills are not maintained, is down to the deeper neurological levels, which are likely to be blocking their progress.

I won’t go into further detail in this blog, but understand this. If you spend all of your time trying to influence behaviour by trying to influence the environment and an athlete’s skills, you may fall short. Because, unless you address the athlete’s deeper psyche you may not achieve any lasting shift in behaviour. Think of the salmon in the earlier video. Fundamentally, their purpose in life is to return to the same river or stream they were born in to give birth to a new generation of salmon. That purpose is so deep in their psyche that even the tremendous flow of water pushing them in the opposite direction will not deter them from behaving a certain way.

Link it to something they value

I said earlier that it is perfectly reasonable to have expectations about behaviour, effort and even personal standards of performance. I also said that the ability of external factors to consistently and permanently influence your action is very limited. That being said, in a team setting the power of the tribe is strong – as humans we fear change and like to conform to the masses. Humans like to fit in.

So while I think it is fine to set standards (which are built around having a set of rules, rewards and punishments for agreed behaviours) for me it is even more powerful when those behaviours are agreed and aligned with the VALUES that are important to the individual and team.

I’ll save it for another blog but if you can get the team to identify values such as we have at APA: Excellence, Respect, Courage, Competitive spirit and Enjoyment, you can relate their behaviours to the values. For example, what behaviours would you expect someone to show who values excellence as a value?

Building Rapport

One of the downsides of dictating rules with rewards and punishments is that the children are not involved in the process. Now clearly, as children they don’t have the same experience of the world as adults, they don’t know what they don’t know, and we need to guide them to the behaviours that are important! But it is important to try and relate to them and build rapport.

So I try to build rapport with younger athletes by:

- Talking with them at their level, both physically and developmentally, to convey respect.

- Ask open-ended questions and listen to learn more about where youth are coming from and their backgrounds, interests, and feelings. “How did that make you feel?” “What was that like?

- Watch for communication roadblocks such as lecturing, judging, and preaching to ensure that you keep doors open for dialogue

- Participate alongside youth to show that you are interested and model risk-taking, competitive spirit, and enjoyment.

- Support opportunities for youth input, shared responsibility, and leadership to help youth develop positive self-efficacy and essential life skills. “Your ideas on how we should approach this are important. What do you think we should do?” “How would you feel about leading the group meeting tomorrow?” “What do you think you could do to help?” “What do you think we could do to make it better?”

Customer Expectations

As a business owner I also think of how the athletes view my coaches and I as a professional company delivering a service. Customer expectations are a set of behaviours or actions that individuals anticipate when interacting with a company. The customer’s expectations revolve around the quality of a service compared to the service’s cost/quality in the past, or in comparison to another service.

As customers they expect companies (such as mine) to understand their needs and expectations they have as an aspiring professional tennis player. They expect us to be professional, passionate and positive (my 3 Ps of Coaching). Customer satisfaction is therefore about meeting customers’ needs and is intrinsically linked to satisfaction with the product or service. Put yourself in your customer’s shoes and treat customers how you would like to be treated yourself. I then like to say to the athlete, now imagine that a coach came on court or in the gym, arrived late, didn’t have a plan, was always on their phone, didn’t give any encouragement or feedback. How would that make you feel?

It is important to shine a mirror on their behaviours and see if they would be happy if their coach showed the same behaviour towards them in their session.

I ask my athletes to share the expectations of me as their coach and it is a useful exercise because they will talk about their ‘customer expectations.’ Invariably it comes back to values…..and asking for feedback is a great way to start developing honesty. I’m asking them to be honest with me.

Honesty implies both truth-telling and responsible behaviour that seeks to abide by the rules. One may trust another person to behave honestly, but honesty is not identical to trustworthiness. A person may be honest but incompetent and so not worthy of trust (firm belief in the reliability, truth, or ability of someone or something).

Honesty builds trust. By being honest, you get people to trust you more.

They want a connection with their coach, they want rapport. Rapport is a relationship built by mutual understanding and trust. In fitness, rapport is the connection a fitness professional and a client or participant seek to establish during their time working together. Rapport involves forming a close connection with a person. It is an authentic expression of acceptance without personal bias (Rogers, 1995). Fitness professionals who create rapport with their clients help shape a relationship of mutual respect and honesty. They want a coach who can connect with them and hold them accountable to high standards.

In a follow up blog I’ll go into more details about communication methods to build rapport and CONNECTION.

Hope you have found this article useful.

Remember:

- If you’re not subscribed yet, click here to get free email updates, so we can stay in touch.

- Share this post using the buttons on the top and bottom of the post. As one of this blog’s first readers, I’m not just hoping you’ll tell your friends about it. I’m counting on it.

- Leave a comment, telling me where you’re struggling and how I can help

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM