Multi SkillZ by Coach2Competence Product REVIEW

Hey everyone. I’ve been doing a bit of self-directed Continued Professional Development (CPD) over the last few days. I decided to purchase the ”Multi Skillz” online video library, produced by Coach2Competence. It cost £266 or 299 Euros for the first year subscription and £35 per year thereafter.

Background on the company:

Kenneth Bastiaens is currently the director and owner of Coach2Competence, a company aimed at developing athletic foundations for young athletes. In 2000 Kenneth was Head of Strength & Conditioning at the High Performance Centre in Belgium. For 9 years he trained athletes such as Kirsten Flipkens, Yanina Wickmayer, Alison Van Uytvanck and Ruben Bemelmans whilst also developing new conditioning pathways. In 2010 Kenneth reformed the Talent ID & Development 12 & under structures for Flemish Tennis. At the highest level, Kenneth was consultant in the coach-player team of Kim Clijsters and travelled on the ATP Tour as a coach for 1 year. With a Masters degree in Kinesiology he is now the driving force behind Multi SkillZ, high quality motor development For Sports, Fun & Success. Kenneth has been strongly involved in Coach Education as a tutor, content manager, speaker and lecturer.

Why did I purchase it?

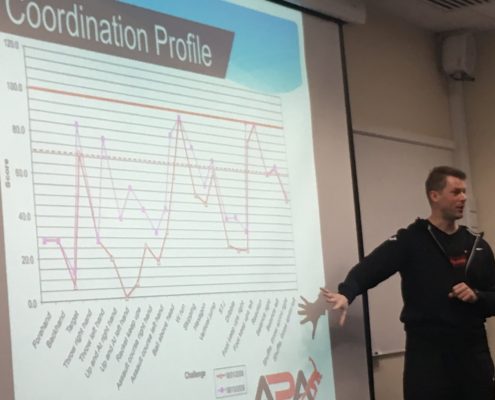

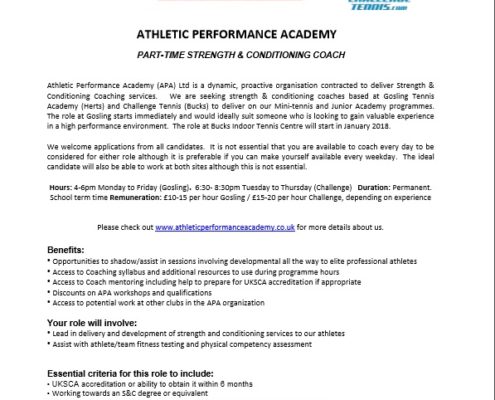

”Motor skills, ”athletic skills” or ”physical competency” or any other word you want to call it is really important. It’s the foundations of movements on which we build sport specific skills. During youth we have to challenge the nervous system as much as possible to be able to solve complex movement puzzles. I’ve always been interested in motor skills training and I consider it to be one of the things APA do really well. But I’m always looking to learn some new ideas and over the years my quest for knowledge has taken me around the globe.

2004-2005

I have picked up some great ideas in recent years on what kinds of activities young children should be doing. Early in my career I picked up a VHS video of ”Coordination training for Tennis” produced by the German Tennis Federation in the very early 1990s. This was a groundbreaking moment in my coaching journey as it made me realise that you can coach coordination skills in some really innovative ways. There I learnt about:

- Differentiation

- Orientation

- Reaction Speed

- Balance

- Rhythm

2007-2008

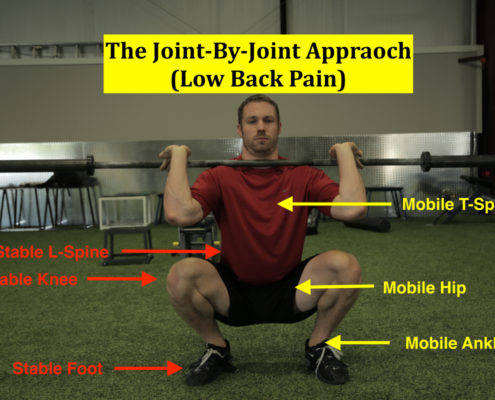

I first came across Kelvin Giles at the UKSCA Strength & Conditioning Conference around 2007 and later in his consultancy role for the Lawn Tennis Association. He helped me to understand how to quantify the quality of fundamental movements that have more of a strength focus- squat, lunge, push, pull, brace, rotate etc.

2010-2011

I studied some more material from SportsCoachUK ”An Introduction to the Fundamentals of Movement” which was a great CDrom on Balance, Coordination, Agility. I also watched the Lawn Tennis Association CD-rom ”Strength & Conditioning Fundamentals- Exercises for under 10s.” It broke fundamental movements down into speed, agility, coordination, strength, power, injury prevention and flexibility.

2015-2016

I came across Ruben Neyens at the Lawn Tennis Association National Coaches Conference in 2015- who did a great presentation on ABCs for children and then the following year Kenneth Bastiaens presented on ”Multi skillZ- motor development for success in sports”. You can only open the link if you are a member of tennis iCoach- but I’d recommend it especially if you work on Tennis as it’s only $30 per year.

So I kept my eyes on these guys and figured that Belgium tennis is leading the way in motor development for children. That lead to me purchasing the Multi SkillZ video library so I can inject some new ideas into my coaching.

OVERVIEW

Here are some of the notes I made paraphrased from some of the online tutorials where Kenneth describes the theory behind the practice

DELIBERATE PLAY- MAKE CHILDREN FOND OF MOVING.

It doesn’t just have to be competition based games!!

- Being creative

- Playing with others

Performing and taking up challenges without there being a specific competition

Show and tell- children design drills for their team mates to copy

Tasks on your own- Getting dizzy putting finger on floor and running around!

They need to feel competent and feel joy at the same time. They want to do things they enjoy!

OUR GREATEST COMPETITION IS THE COMPUTER GAME. Computer games are organised in levels and children are challenged over and over again. Therefore it is our job to do that too. Children need to experience ‘motor gaming.’

MOTOR COMPETENCE is foundation for SPORT SKILL

The goal is NOT to improve certain movement patterns or movement techniques. We emphasis motor abilities referred to as the sub factors of the different development domains. We do not stick to specific drills or exercises. On the contrary we would like to expose the children to continuously changing situations and movement tasks. In this way we believe we accelerate motor learning and motor abilities.

FUN and stimulating

A Multi SkillZ drill meets 5 standards. The i5-approved drills:

- Invite participants to play or move

- Intensive

- Intriguing as it takes the attention of each participant constantly

- Implicit learning

- Interactive as participants are challenged to work together

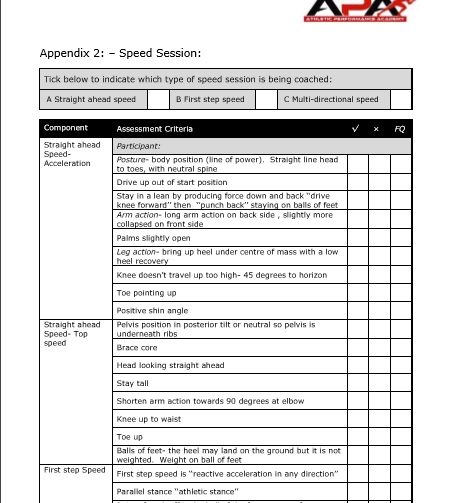

There are separate drills for Fitness, Skills, Function and Speed. Each drill challenges the participant’s motor ability, problem solving behaviour and cognitive skills. The interactive nature of the fun play exercises enables participants to learn social skills and core values such as trust, creativity and cooperation.

The main components above are further subdivided into four sub-categories per motor ability. So you get 16 components all together. For each sub category there are at least three drills- each drill has red, orange and green version. For each colour- red, orange or green there are also usually three levels of difficulty so there is plenty of differentiation to accommodate the different abilities not only across colours but within colours!!

At APA we use the 5 S’s of fitness to classify the fitness components (Skill, Suppleness, Strength, Speed, Stamina) but regardless of how you categorise things I can definitely say there is plenty of new concepts I took away. The concept of the i5- approved drills is something I really liked. I have to say that I was impressed how literally EVERY drill ticked all those boxes. Literally every child had a job/instruction to follow in every drill even when they weren’t the one performing the task.

THEORY

In addition to the video library there are 22 online tutorials that cover some really important topics such as motivation, working with parents, periodisation, and long term athlete development.

Kenneth talking about Long-term Athlete Development.

In the next blog I will talk a little about one of the concepts Kenneth mentioned ”Periodisation for Kids.”

FINAL THOUGHT

There are loads of products out there but for me this is one of the best ones out there. If you’re someone who wants to know more about the specific ‘techniques’ of movement and how to coach the specifics of squats and press ups and running technique etc this might not be for you. The authors of this product want the learning to be as implicit as possible. So apart from the demos where the coach role models good technique it is pretty much move and play throughout.

I come from a very technical background so I’m actually looking for a resource that will encourage me to use more play activities and less technical instruction. If you’re looking for something similar then this is the one for you.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. APA aim to bring you compelling content from the world of sports science and coaching. We are devoted to making athletes fitter, faster and stronger so they can excel in sport. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — APA TEAM